Reforms in the military and its timely up-gradation to keep pace with the changing global advancements forms among the most important elements of national security. Failure to undertake military reforms may result – if not in immediate security costs – in long-term erosion of capabilities. It is in this context that the Agnipath Scheme has been launched by the government. The scheme has corresponding models already in existence in all major military powers in the world, such as the U.S, the U.K, Russia, Israel, France and Germany, which were studied extensively over the past two years before the scheme for India was formulated.

The scheme aims to contribute to military reforms by changing the profile of the non-officer rank military personnel and by ensuring that more resources can go towards military modernization, which is the need of the hour. It also ensures tangible and intangible benefits for the ‘Agniveer’ graduating from this scheme into the society, towards the larger cause of nation-building.

Stilted Trajectory of Military Reform

India has had an uneasy relationship with military reforms. The country’s civilian leadership – for several previous decades – was unwilling to cede military control to military brass itself, opting instead to keep the military under the control of civilian leadership. This was done by populating the defence decision-making arena with civilian bureaucrats, who also happened to be non-experts in military matters. In the immediate post-Independence period, such an approach may have been rational. For, around us abounded examples of newly decolonized countries in Asia and Africa who had, after brief stints with democracy, fallen into the trap of dictatorships.

However, this combination of overpowering civil control over a large, semi-autonomous military soon became outdated. Civilian bureaucratic control had its disadvantages, the most prominent amongst them being the compromise of military effectiveness, the tendency of services to operate in silos and manipulation and corruption in defence contracts and procurement. Indeed, such was the state of affairs that the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) was constituted only in the mid-1990s. Until then, national security issues were handled by the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) in addition to its various other wide political responsibilities. Prior to the Kargil War of 1999, defence reforms were undertaken in an ad hoc, sporadic and reactionary manner in response to occurrences rather than with a long-term strategy or vision (Kanwal & Kohli, 2019).

Despite our operational difficulties in the initial phase of the Kargil War and the subsequent recommendations made by the Kargil Review Committee, military reforms were not adequately undertaken. Indeed, the Kargil Review Committee, under the Prime Ministership of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, was the first instance of sweeping defence reforms being deliberated at all. It made wide-ranging recommendations in various areas pertaining to defence preparedness, procurement, and military expenditure, including recommendations for integration of the military through the creation of the post of Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) and reducing the age of personnel being recruited to the military. Many of the recommendations were adopted, while many critical ones were left out.

Under the subsequent governments of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh (2004 to 2014), military reforms were completely put on the backburner and, indeed, relations between political and military leadership were highly strained (Mukherjee, 2021). It was only after Prime Minister Modi assumed power in 2014 that military reform began to take priority.

While in the first term of the government military expenditure fell to an all-time low, in the second term of the government sweeping military reforms began to be undertaken, which had been pending for the last three decades. Key reforms include the creation of the post of CDS tasked with theaterization of military command and the creation of the Department of Military Affairs (DMA). Reforms also included a special focus on infrastructural projects – such as the construction of roads, bridges and other connectivity projects – with a strategic value in border areas of the country.

The government also laid immense emphasis on accelerating the production of the indigenous defence industry, by increasing defence exports and undertaking reforms like the corporatization of the ordnance factories. In this, the biggest psychological change has been to overcome the historically friction-ridden relationship between the defence industry and the military sector and make them work with each other, thereby mitigating the suspicious military attitude towards the private sector. Finally, the government also began to involve the military in diplomatic and foreign policy priorities, unlike in the past when the military was often left guessing about the foreign policy priorities.

Agnipath – A Reform Long Due

It is in this long line of military reforms undertaken under the Modi government that the Agnipath or ‘Tour of Duty’ scheme was launched in mid-June 2022. It is a scheme for recruitment of Personnel Below Officer Ranks (PBORs) to the army, navy, and air force. The scheme – with recruitment effective from July-August 2022 – will now be the only mode of recruitment of soldiers, sailors and airmen. It will recruit youth aged between 17.5 and 21 years – with the upper age limit being raised to 23 years for 2022 as a concession to protestors – for a period of four years, which includes six months of the training period. After the end of the four-year period, 25% of these Agniveer will have the option of continuing forward to regular military service, while the rest of the 75% will enter the society.

The reform has echoes in some of the recommendations of the Kargil Review Committee which had suggested reducing the age of the military personnel and made recommendations regarding streamlining defence expenditure. The Agniveer scheme fulfils all these imperatives. It effectively brings down the average age of personnel from the present 32 years to 25 years. The requirement for a younger profile of the military cannot be emphasized enough. For, a youthful profile of the army not only provides more energy and spirit to the forces and is more amenable to the latest technological integration, but also moulds and shapes impressionable young minds in a positive direction before the venom of the present utilitarian education system could seep into them.

Presently, the average age of soldiers in the Indian army is around 32 to 33 years. Only 19% of the personnel below officer’s rank (PBOR) are below the age of 25 years; 27% are in the age group of 26 to 30 years, 20% are in the 31-35 years bracket, 19% are in 36-40 years category; around 10.2% are in 41-45 years category and 4.4% are in 46-50 years bracket (Gupta, 2022).

Besides reducing the average age of the personnel, the scheme also ensures that a larger share of the defence budget is made available for capital expenditure for the acquisition of high-technology military equipment and platforms over time. This will be ensured as – due to the Agnipath scheme – the expenditure on defence pensions is expected to drop substantially over time.

Myth Versus Reality – What the Scheme is Really About

While the scheme is a concrete measure – based on other countries’ experiences and needs of the hour – to revamp the military and also have an impact on society, the objections to it appear to be based on superficial grounds, projected too far into the realm of speculations. These objections have been raised from political quarters and retired army veterans. The immediate negative reactions of the Opposition have also led to planned protests, violence, and arson in various states, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. In many cases, these protests were pre-planned, and a result of a conspiracy, with coaching centres being busted for masterminding protests and inciting people.

As is the norm with reactions spawned from mass mentality, even in the case of this scheme the objections are born more out of speculative insecurity and fear of the unknown rather than anything concrete. They need to be addressed to show their superficiality.

First, the objections assume that the government’s attempt to save on revenue expenditure will be at the cost of the ‘operational capabilities and efficiency’ of the forces. There is no concrete proof to support this assumption. Indeed, facts show the reality to be the exact opposite. Major defence expenditure goes towards pensions and salaries, while very little is left for spending on equipment that can enhance the ‘capabilities and efficiency’ of the forces. The Agnipath scheme, by saving on pensions, is actually allocating a huge chunk of expenditure to capital expenses that, in turn, can help improve the efficiency of the forces.

Presently, more than half the defence budget is allocated for pensions every year while less than 5% is allocated for research and development.

In the last seven years alone, the number of defence pensioners has increased by around 10 lakh personnel. In the defence allocation, about 70% of the defence budget is being used for revenue expenditure (operating expenses), while only about 30% is spent on capital expenditure, which is meant for the modernization of the military (Varghese, Radhakrishnan, & Nihalani, 2022).

Thanks to the amount of money spent on pensions – which has increased enormously due to the Prime Minister’s fulfilment of the One Rank One Pension (OROP) pledge – the modernization of forces has taken a hit. It is estimated that the Indian Air Force (IAF) presently has 30 squadrons of fighter jets against the 42 that are needed, and the Indian navy has 130 ships as against the 200 that it envisages (Singh, 2022).

In the years to come, India will be faced with a much more insecure world and new forms of warfare for which we need to be appropriately geared up. The global insecurity is visible in the field of the arbitrariness with which certain countries are ready to violate principles of sovereignty and upend the international order – as is visible in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This has led to new forms of alliances, arms race and massive economic fallout.

The world is also facing new forms of warfare which will be increasingly driven by non-contact warfare, automated warfare driven by Artificial Intelligence technologies and warfare based on other forms of advancing, manipulative/deceptive technologies and fifth-generation weapons and military systems. It will be based less on numbers and more on technology, driven by stand-off weapons, cyberspace and space-based ISR (Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance) (Chinoy, 2022). Therefore, the need of the hour – as acknowledged by the whole world – is a thinning, rather than an expansion of armed forces, and more induction of automated weapons systems, including the capability to manufacture them indigenously.

Second, the objections assume that at the end of the four-year period, the 75% of the youth entering society would be ‘unemployable’. This is yet another baseless assumption. In fact, the rest – 75% – of the Agniveer will enter society armed with the advantages of military discipline, feeling of nationalism and character-building and with numerous material benefits as well. They will be expected to provide an inspirational and leadership role in society that is moving toward nationalism as an important part of nation-building.

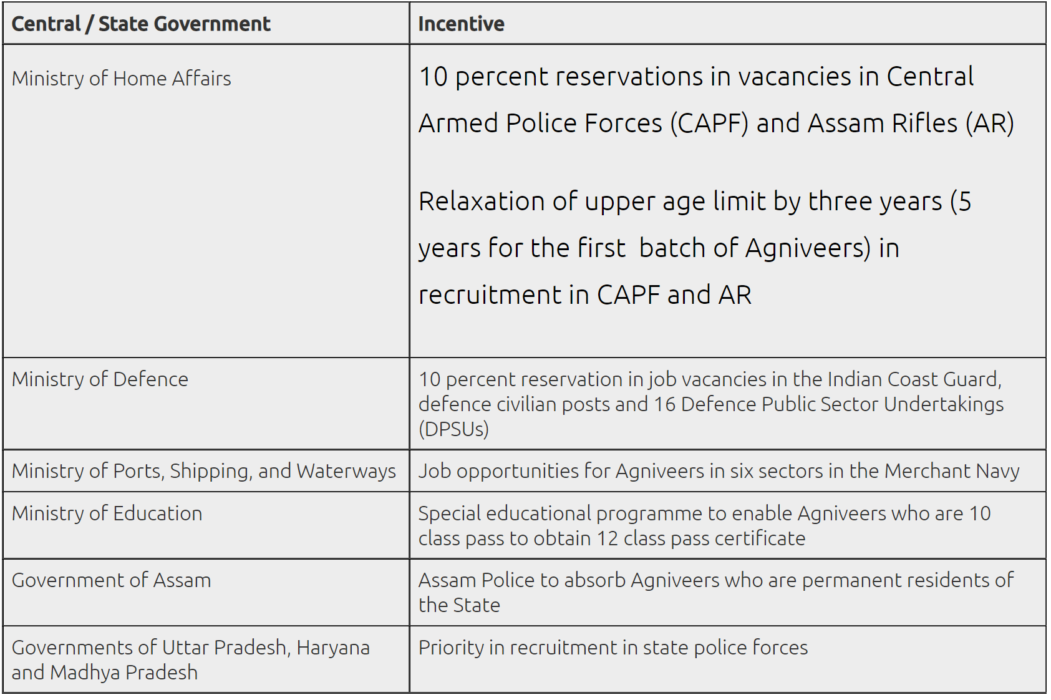

They will also – due to the education and training imparted to them – be expected to come with an advanced skill set that will provide them material opportunities in various sectors where they can contribute. In terms of material benefits to be given to them, they will have a good salary package, certification in terms of specially-designed government education, skills as well as options to avail special reservations announced by various states and departments. The Seva Nidhi package that will be given to them can be used to start their own business or can be invested.

Source: Behera (2022)

Various business leaders across the country have also welcomed the scheme and announced their eagerness to employ the disciplined Agniveers who enter the society. In other words, the Agniveer will be much better off than their peers who would – given the present state of the economy worldwide and in India, and the rapidly deteriorating psychological and material conditions of the mass of humanity – be likely unemployable and saddled with futile degrees.

Moving Beyond Inertia

The working of the scheme and its impacts will become clearer over time. Presently, Indian Air Force (IAF) Agnipath recruitment has seen around 7.5 lakh applications, showing that the youth is applying with full enthusiasm. The virulent protests against the scheme lasted for barely a few days. As soon as the government made its intent clear that the scheme will not be rolled back and that those participating in the protests will not be allowed to compete for recruitment to the scheme, the protests were quick to dissipate. The Opposition – as expected – kept attempting unsuccessfully to resurrect the fires of anarchy long after the protests had quietened down.

Despite the dissipation of protests, a new facet of the country was revealed. The manner in which the protestors engaged in violence, involving damage, burning and destruction of national property like trains and other infrastructure, showed how divided we still are, as a country. It is ironic that the arsonists and rioters engaging in such national damage are the ones who planned to be recruited to the task of serving the nation through the military. The mentality that the appeal of military service should hinge on a life-long pension and a life of comfort after serving for 15 years is akin to the mentality seeking government service as a secure way of economic survival. These utilitarian notions of comfort and security are now being challenged as the country moves forward after a sustained collective inertia of many decades.

It is this utilitarian thinking which has prevented nationalism from taking root among the mass of people. Defence constitutes one of the most critical public services, but under the onslaught of utilitarianism, the very meaning of service itself has been subverted. Instead of motivating the spirit of serving others or serving an aim higher than ourselves (such as the nation or the Divine), the term service has begun to imply a professionalized catering to one’s own selfish interests instead of serving the country or society. Livelihood is a necessity, but when service becomes a means for only serving ourselves at the cost of the country, it becomes perverted. This is what is visible in the India of today. It is visible not only in the Agnipath protests but also in the mass mentality of the Hindus on other issues, where abhorrent fear and insecurity about our own narrow interests prevent us from uniting as a nation. Such fear – an outgrowth of tamasic inertia – is perhaps as perverted, if not worse than utilitarianism.

The overwhelming concern with our own future and security – especially for those engaged in public service – ought to give way to more of the spirit of self-giving. Such a spirit would be particularly needed, in the area of defence, if a nation were to face a crisis. For instance, the manner in which Ukrainian people united to fight against the Russians is exemplary and unlikely to be seen in a divided India of the present times. This state of affairs needs to change and tinkering with the mere outer machinery by introducing new laws or policies or systems cannot bring about such a change. In that sense, Agnipath is only a partial and a small step in the right direction. But it appears that the nation is poised to go through much collective hardship before it gets rid of its self-serving inertia and truly awakens the dynamic national spirit from within. Until that is done, these outer steps will merely serve symbolic and decorative purposes.

Bibliography

Behera, L. (2022, June 22). Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/a-bold-new-defence-recruitment-scheme/

Chinoy, S. (2022, June 15). The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/sujan-r-chinoy-writes-a-reform-called-agnipath-scheme-government-of-india-armed-forces-aiac-7969520/

Gupta, S. (2022, June 20). Hindustan Times. Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/why-a-young-fitter-and-tech-savvy-agniveer-is-the-only-answer-to-china-101655701801040.html

Kanwal, G., & Kohli, N. (. (2019). Defence Reforms: A National Imperative. New Delhi: Pentagon Press and Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis.

Mukherjee, A. (2021, May 5). THE GREAT CHURNING: MODI’S TRANSFORMATION OF THE INDIAN MILITARY . Retrieved from War on the Rocks: https://warontherocks.com/2021/05/the-great-churning-modis-transformation-of-the-indian-military/

Singh, S. (2022). Agnipath, a fire that could singe India. New Delhi: The Hindu.

Varghese, R., Radhakrishnan, V., & Nihalani, J. (2022). Agnipath and Pensions. New Delhi: The Hindu.