VII. How to Recover the Perfect Truth of the Veda

A. The Supreme Importance of the Recovery

“…by the inexorable vicissitudes of Time, we have lost the sense of Veda and do not possess the full sense of Vedanta…. We possess intellectually the general truths of Vedanta, the transcendental unity of things and the universal unity, ekam adwitiyam Brahma and so’ham asmi; the secret of divine renunciation of the Ascetic and the secret of divine joy of the Vaishnava, with much else that is sovereign, vital, a priceless heritage. We possess many symbolic forms of religious application by which we enter into possession of the eternal truth through the emotions, through the intellect or through active experience in our inner life & outward relations. We possess numerous methods & forms of psychological discipline by which we repeat old profound experiences and do even actually possess many apparently lost details of Vedic truth preserved in another form and couched in more modern symbols. All this is much; it has kept us alive through the centuries. But it is only in its totality that the Truth can work its utter miracles. Otherwise, if we live on her broken meats we tend either to lose ourselves in the outer formulae or concentrate dogmatically on fragments & sides of the living truth; when great spirits arise to give us their deep & vast experience, we prove ourselves limited and shallow vessels and are unable to receive more of the truth than is in harmony with our confined intellects and narrow natures; and, if powerful floods of materialism invade us, as in the present European era of humanity, we have not the strength to resist, to hold fast to that which is difficult but enduring; we are overborne, lose our footing and are carried away in the vehement but shallow currents. Perfection of knowledge is the right condition for perfection of nature and efficiency of life. The perfect truth of the Veda is the fundamental knowledge, the right relations with the Truth of things, on which alone according to our ideas, all other knowledge can receive the true orientation needed by humanity. The recovery of the perfect truth of the Veda is therefore not merely a desideratum for our modern intellectual curiosity, but a practical necessity for the future of the human race. For I believe firmly that the secret concealed in the Veda, when entirely discovered, will be found to formulate perfectly that knowledge and practice of a divine life to which the march of humanity, after long wanderings in the satisfaction of the intellect and senses, must inevitably return and is actually at the present day, in the impulses of its vanguard, tending more and more, but vaguely and blindly, to return. If we can set our feet on the path, not vaguely and blindly, but in the full light that streamed so brilliantly and grandiosely on the inner sight of our distant forefathers, our speed will be more rapid and our arrival more triumphant.”1

B. The True and the Only Means of the Recovery

“The perfect truth of the Veda, where it is now hidden, can only be recovered by the same means by which it was originally possessed. Revelation and experience are the doors of the Spirit. It cannot be attained either by logical reasoning or by scholastic investigation, – na pravachanena, na bahuná srutena . . . na tarkenaishá matir apaneyá. ‘Not by explanation of texts nor by much learning’ . . . ‘not by logic is this realisation attainable.’ Logical reasoning and scholastic research can only be aids useful for confirming to the intellect what has already been acquired by revelation and spiritual experience. This limitation, this necessity are the inexorable results of the very nature of Veda.

It is ordinarily assumed by the rationalistic modern mind, itself accustomed to arrive at its intellectual results either by speculation or observation, the metaphysical method or the scientific, that the sublime general ideas of the Upanishads, which are apparently of a metaphysical nature, must have been the result of active metaphysical speculation emerging out of an attempt to elevate and intellectualise the primitively imaginative and sensational religious concepts of the Veda. I hold this theory to be an error caused by the reading of our own modern mental processes into the very different mentality of the Vedic Rishis. The higher mental processes of the ancient world were not intellectual, but intuitive. Those inner operations, the most brilliant, the most effective, the most obscure, are our grandest and most powerful sources of knowledge, but to the logical reason, have a very obscure meaning and doubtful validity. Revelation, inspiration, intuition, intuitive discrimination, were the capital processes of ancient enquiry. To the logical reason of modern men revelation is a chimera, inspiration only a rapid intellectual selection of thoughts or words, intuition a swift and obscure process of reasoning, intuitive discrimination a brilliant and felicitous method of guessing. But to the Vedic mind they were not only real and familiar, but valid processes; our Indian ancients held them to be the supreme means of arriving at truth, and, if any Vedic Rishi had composed, after the manner of Kant, a Critique of Veda, he would have made the ideas underlying the ancient words drishti, sruti, smriti, ketu, the principal substance of his critique; indeed, unless these ideas are appreciated, it is impossible to understand how the old Rishis arrived so early in human history at results which, whether accepted or questioned, excite the surprise and admiration even of the self-confident modern intellect…. But, whatever the validity attached to them or the lack of validity, it is only by reproducing the Vedic processes and recovering the original starting point that we can recover also whatever is, to the intellect, hopelessly obscure in the Veda and Vedanta. If we know of the existence of a buried treasure, but have no proper clue to its exact whereabouts, there are small chances of our enjoying those ancient riches; but if we have a clue, however cryptic, left behind them by the original possessors, the whole problem is then to recover the process of their cryptogram, set ourselves at the proper spot and arrive at their secret cache by repeating the very paces trod out by them in their lost centuries.

All processes of intellectual discovery feel the necessity of reposing upon some means of confirmation and verification which will safeguard their results, deliver us from the persistent questioning of intellectual doubt and satisfy, however incompletely, its demand for a perfectly safe standing-ground, for the greatest amount of surety. Each therefore has a double movement, one swift, direct, fruitful, but unsafe, the other more deliberate and certain. The direct process of metaphysics is speculation, its confirmatory process is reasoning under strict rules of verbal logic; the direct process of science is hypothesis, its confirmatory process is proof by physical experiment or by some kind of sensational evidence or demonstration. The method of Veda may be said to have in the same way a double movement; the revelatory processes are its direct method, experience by the mind and body is the confirmatory process. The relation between them cannot, indeed, be precisely the same as in the intellectual methods of metaphysics and science; for the revelatory processes are supposed to be self-illumining and self-justifying. The very nature of revelation is to be a supra-intellectual activity occurring on the plane of that self-existent, self-viewing Truth, independent of our searching and finding, the presumed existence of which is the sole justification for the long labour of the intellect to arrive at truth. In Veda drishti and sruti illumine and convey, the intellect has only to receive and understand. Experience by the mind and body is necessary not for confirmation, but for realisation in the lower plane of consciousness on which we mental and physical beings live. We see a truth self-existent above this plane, self-existent in the satyam ritam brihat of the Veda, the True, the Right, the Vast which is the reality behind phenomena, but we have to actualise it on the levels on which we live, levels of imperfection and uncertainty, striving and seeking; otherwise it does not become serviceable to us; it remains merely a truth seen and does not become a truth lived. But when we moderns attempt to repeat the Vedic revelatory processes, experience by the mind and body becomes an indispensable confirmatory process, even a necessary preliminary process for their acquisition; for the use of these supreme instruments of intuitive and revelatory knowledge is naturally attended, for those to whom the intellect is and has always been the chief and ordinary mental organ, by dangers and difficulties which did not to the same extent pursue the knowledge of the ancient Rishis. To them it was natural in its possession, easily purified in its use; to us it is a difficult acquisition, hampered in its use by the interference of the lower movements. Experience is, for us, indispensable; we may not be certain of excluding by its means all false sight and false intuition, but we can correct much that has been imperfectly seen and confirm beyond the possibility of all intellectual scepticism that which does clearly come down to us as illumination from our Higher self to be confirmed in life and experience, constantly and regularly, by our lower instruments.

We have, for instance, the remarkable passages in the Isha Upanishad about the sunless worlds, the luminous lid concealing Truth, the marshalling and concentration of the rays of Surya and his goodliest form of all, that form which, once seen, leads direct to the supreme realisation of oneness, So’ham asmi. Our intellect sees in these expressions a brilliant poetry, but no determinable philosophical sense; yet no one can follow thoughtfully the succession of the phrases without feeling that the Seer of the Upanishad did not really intend to lead up to the direct clarity of his supreme philosophical statement by a flight of vague poetical images; he has a more serious meaning, detailed, definite, precise, pregnant, in the carefully arranged procession of these splendid images. How are we to discover it? Using the scholastic method we may hunt for a clue in the other Upanishads; we may find it or imagine we have found it and by the aid of speculative inference and a liberal dose of fancy we may construct a brilliant or even a plausible theory of the Rishi’s meaning. Or, without any such clue, by the aid of a clear intelligence and putting together of the ascertainable ideas of Veda or Vedanta, we may fix a meaning which will adequately explain the text, fit into the course of the argument and, in addition, justify itself by shedding light on other passages where there is a reference to the Sun, to its rays or to its revelatory function. These means, however, can only conduct us to a plausible hypothesis, a twilight certainty, or at most a convincing probability. Nor, in this passage at least, will the metaphysical methods of Shankara at all assist us; for it is a question not of metaphysical logic but of the meaning of an ancient symbol, the connotation of certain antique figures. On the other hand, if we have been able to revive by Yoga the old methods used by the ancients themselves, we may, either in the ordinary course of our experiments or guided by the suggestion of the Upanishad, arrive at the actual experiences on which, in Vedic times, the use of this symbol and these figures was founded. We may perceive in our own selves the interposition of the golden vessel, the action of the rays, their disposition, their concentration; we may have the vision of the goodliest form of all, tejo yat te rupam kalyanatamam, and know, by luminous experience, the link between that vision and the realisation of the supreme Vedantic truth, So’ham asmi. We shall then be certain of our knowledge, our unity with the one and only existence. If the ancient ideas of our psychology are correct, by process of revelation and intuition we could have arrived at the same results; the old Rishis, accustomed to use that process habitually and follow its progressive action with as much surety and confidence as we follow the steps of a logician, would have needed nothing more for certainty, though much more for realisation; but we, habitually intellectual, pursued into the higher processes, when we can arrive at them, by those more brilliant and specious movements of the intellect which ape their luminosity and certainty, could not feel entirely safe and even, one might say, ought not to feel entirely safe against the possibility of error. The confirmation of experience is needed for our intellectual security.

This method, by which, as I hold, the meaning of Veda can alone be entirely recovered, is, then, a process of psychological experiment and spiritual experience aided by the higher intuitive or revelatory faculties, – the vijnana of Hindu psychology, – of which mankind has not yet, indeed, anything but a fitful and disordered use, but which are capable of being, within certain limits, educated and put into action even in our present transitional and unsatisfactory stage of evolution. It differs from the method by which the ancient Rishis received Vedic truth, – revelation confirmed by experience, – only by the side of approach which must be for us from below, not from above, and the weight of the emphasis which must rest for a mentality preponderatingly intellectual and only subordinately intuitional, on experience more than on intuition. For the rest, the common consent of humanity has agreed that only by higher than intellectual faculties can the truths of a supra-human or supra-sensuous order, if at all they exist, be really known. Religion, except in ethical and rationalistic creeds like Buddhism and Confucianism which have put aside all such questionings as outside the human domain, has always insisted that revelation is the indispensable angel and intermediary and the intellect at best only its servant, assistant and pupil. Science and rationalism have virtually agreed to this distinction; they have accepted the idea that all knowledge, which does not reach us through the doors of the senses and, on its arrival, submit its pretensions to the judgment of the reason, is incapable of solution by the intellect; but they add that, for this very reason, precisely because the senses are our only doors of experience and the reason our only safe counsellor, the questions raised by religion and metaphysics are utterly vain and insoluble; they relate either to the unknowable or the non-existent; either the material only exists, or, if there is any other existence, the material only can be known and therefore alone exists for the purview of humanity. As man marches upon the dust and is circumscribed by the pressure of the terrestrial atmosphere, so also his thought moves only in the material ether and is circumscribed within the laws and results of material form and motion. Recently we see, even in Europe or chiefly in Europe, – for Asia is too busy imitating Europe of yesterday to perceive whither Europe of today is tending, – a revolt against this arbitrary denial of the rarest parts of human experience. The existence of the supra-sensuous and the infinite is reconquering belief and, at the same time, it is coming again to be admitted that there are faculties of intuitive and supra-rational knowledge which answer in the domain of Consciousness to these supra-sensuous facts of the domain of Being. The belief and the admission go together rationally. For to every order of facts in Nature there should be in the same Nature, inevitably, a corresponding order of faculties in knowledge by which they can be comprehended; if we have no certain knowledge of the facts, it is because we have not as yet the clear and steady use of the faculties.

In three of the external aids by which Veda has been perpetuated in India, religion, Yoga, the guru-parampara, this fundamental principle is amply admitted. Religion starts from revelation; it rests upon spiritual and moral experience. Yoga, admitting the truth of verbal revelation, the word of God and the word of the Master, yet starts from experience and rises, as a result of experimental development by fixed methods, to the use of intuitive and revelatory knowledge. The Guru-parampara starts with the word of the Guru, accepted as the knowledge of one who has seen, and proceeds to personal mastery by the experience of the disciple who may indeed go beyond his master and even modify his knowledge, but is not allowed to disown his starting-point.”2

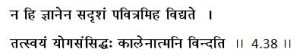

Thus, those higher faculties which alone can enable one to have the truer knowledge are to be developed by the pursuit of Yoga. In the words of the Gita;

This may be rendered in English thus, “There is nothing in the world equal in purity to knowledge, the man who is perfected by Yoga, finds it of himself in the self by the course of Time.”

“The Gita in describing how we come by this knowledge, says that we get first initiation into it from the men of knowledge who have seen, not those who know merely by the intellect, its essential truths; but the actuality of it comes from within ourselves: ‘the man who is perfected by Yoga, finds it of himself in the self by the course of Time,’ it grows within him, that is to say, and he grows into it as he goes on increasing in desirelessness, in equality, in devotion to the Divine. It is only of the supreme knowledge that this can altogether be said; the knowledge which the intellect of man amasses, is gathered laboriously by the senses and the reason from outside. To get this other knowledge, self-existent, intuitive, self-experiencing, self-revealing, we must have conquered and controlled our mind and senses, samyatendriyah, so that we are no longer subject to their delusions, but rather the mind and senses become its pure mirror; we must have fixed our whole conscious being on the truth of that supreme reality in which all exists, tat-parah, so that it may display in us its luminous self-existence.”3

“Always in this sense of a supreme self-knowledge is this word jnana used in Indian philosophy and Yoga; it is the light by which we grow into our true being, not the knowledge by which we increase our information and our intellectual riches; it is not scientific or psychological or philosophic or ethical or aesthetic or worldly and practical knowledge. These too no doubt help us to grow, but only in the becoming, not in the being; they enter into the definition of Yogic knowledge only when we use them as aids to know the Supreme, the Self, the Divine, – scientific knowledge, when we can get through the veil of processes and phenomena and see the one Reality behind which explains them all; psychological knowledge, when we use it to know ourselves and to distinguish the lower from the higher, so that this we may renounce and into that we may grow; philosophical knowledge, when we turn it as a light upon the essential principles of existence so as to discover and live in that which is eternal; ethical knowledge, when by it having distinguished sin from virtue we put away the one and rise above the other into the pure innocence of the divine Nature; aesthetic knowledge, when we discover by it the beauty of the Divine; knowledge of the world, when we see through it the way of the Lord with his creatures and use it for the service of the Divine in man. Even then they are only aids; the real knowledge is that which is a secret to the mind, of which the mind only gets reflections, but which lives in the spirit.”4

To acquire real knowledge faith is necessary, “if faith is absent, if one trusts to the critical intelligence which goes by outward facts and jealously questions the revelatory knowledge because that does not square with the divisions and imperfections of the apparent nature and seems to exceed it and state something which carries us beyond the first practical facts of our present existence, its grief, its pain, evil, defect, undivine error and stumbling, asubham, then there is no possibility of living out that greater knowledge. The soul that fails to get faith in the higher truth and law, must return into the path of ordinary mortal living subject to death and error and evil: it cannot grow into the Godhead which it denies. For this is a truth which has to be lived, – and lived in the soul’s growing light, not argued out in the mind’s darkness. One has to grow into it, one has to become it, – that is the only way to verify it. It is only by an exceeding of the lower self that one can become the real divine self and live the truth of our spiritual existence. All the apparent truths one can oppose to it are appearances of the lower Nature. The release from the evil and the defect of the lower Nature, asubham, can only come by accepting a higher knowledge in which all this apparent evil becomes convinced of ultimate unreality, is shown to be a creation of our darkness. But to grow thus into the freedom of the divine Nature one must accept and believe in the Godhead secret within our present limited nature. For the reason why the practice of this Yoga becomes possible and easy is that in doing it we give up the whole working of all that we naturally are into the hands of that inner divine Purusha. The Godhead works out the divine birth in us progressively, simply, infallibly, by taking up our being into his and by filling it with his own knowledge and power, jnanadipena bhasvata; he lays hands on our obscure ignorant nature and transforms it into his own light and wideness. What with entire faith and without egoism we believe in and impelled by him will to be, the God within will surely accomplish. But the egoistic mind and life we now and apparently are, must first surrender itself for transmutation into the hands of that inmost secret Divinity within us.”5

References:

- Sri Aurobindo Archives and Research, Issue December 1985, pp. 167-68, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry

- Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol.17, pp. 551-57, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry

- Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol.19, p.204, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry

- Ibid., pp. 203-04

- Ibid., pp. 309-10