The India-Nepal boundary issue has assumed a new and unnecessarily hostile dimension after the Nepali escalation on the issue in response to India’s inauguration of the Lipulekh Pass. On May 8th, Indian Defence Minister virtually inaugurated the Lipulekh Pass to connect Indian state of Uttarakhand with Lipulekh (which lies at the India-Tibet-Nepal trijunction). Kalapani is strategically as well as culturally important for India, providing the shortest route connecting India with Tibet. However, Nepal has raised the objection that the road cuts through the disputed area of Kalapani which is claimed by Nepal as well as India, but whose actual control (as part of Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh district) has been with India since decades.

The present issue has arisen as a result of confrontational psychological posturing by the Nepalese Prime Minister, KP Sharma Oli, who has been on a quest to divert attention from the domestic political troubles that threaten to end his tenure. The careless and hostile manner in which Nepal officially and unilaterally stamped its cartographic claims has ended up straining India-Nepal relations and painting Nepal into a corner from which it will find it difficult to come out.

Border Dispute in the Context of India-Nepal Relations

Relations between India and Nepal span centuries of cultural, spiritual, socio-economic and political ties, going back to as early as 6th century BC. From Pashupatinath to Kashi Vishwanath and from Ayodhya to Janakpuri, India-Nepal ties are foregrounded mainly in a common religion and heritage. This common cultural and religious heritage has made possible the easy political and economic linkages that are visible today. Ruling dynasties during the centuries of monarchy era in Nepal have traced their lineage to Kshatriyas.

The military ties among the two countries have been seamless. The Army Chiefs of both the countries hold the rank of Honorary Generals in each other’s armies. Gorkhas serve in large numbers in the Indian Army – presently, around 32,000 – with seven regiments and 40 battalions, most of them recruited from Nepal, with the number of Nepalis drawing an Indian Army pension reaching nearly 130,000 (Singh M., 2020). Besides, nearly 8 million Nepalese people (according to official figures) live and work in India. Around 600,000 Indians are living in Nepal (Embassy of India, 2015).

The distinctive and unique relationship between the two armies is complemented by the open borders between the two countries wherein the citizens of either country can cross over into each other’s territory without any need for passport or visa. The Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1950) has governed the political relationship between the two countries, leading to such seamless interlinkages viz. ‘roti-beti’ or ‘livelihood-marriage’ ties as they are called.

Kathmandu Valley has been the core centre of Nepal’s national activity over the past few centuries. Nepali leadership considerably weakened after the 15th century, when the Valley was divided into three competing kingdoms – Kathmandu, Patan and Bhadgaon. After this, for few centuries there was no powerful ruler or dynasty in Nepal. During this period, Muslim rulers of India attacked and plundered Nepal many times , but could not conquer it. It was only in the 18th century that Nepal got its first powerful ruler in the modern era viz. Prithvi Narayan Shah, who conquered Kathmandu Valley and unified Nepal into a nation in 1769. Prior to that the boundaries and identity of Nepal were limited to the Kathmandu Valley only.

Like other Nepali rulers, Prithvi Narayan Shah also traced his lineage to Rajputs of India, specifically of Chittor, and proclaimed Nepal as the real ‘Hindu’ nation, since India was then under the rule of the Mughals. Sometime after the late 18th century, Nepal began to aggressively expand in all directions, attacking Sikkim in east, Kangara in the west (checked by Maharaja Ranjit Singh) and their advance was sharply checked by the Chinese in the north also. They also systematically expanded in the south towards the fertile Terai region, which initially went unchecked due to passive policy of the Britishers.

It was under Bhim Sen Thapa’s rulership that this expansion took place and relations between India and Nepal fell to their lowest in the 19th century, with the war of 1814-16 being fought. The magistrate of Tirhut reported occupation of more than 200 villages by Gorkhas at different times between 1787 and 1812. In Bareilly, 5 out of 8 divisions were occupied, and an extensive tract was occupied in Moradabad and in Sarun and Gorakhpur districts, as well as areas under protection of Sikh chiefs.

The British, on their part, were also trying to establish hegemony in Asia and had tried multiple times via East India Company to set foot in Nepal, but to no avail. The British particularly eyed the Kumaon and Garhwal regions and the connectivity to Tibet that they would provide. Bhim Sen Thapa’s expansionism gave an opening to instigate the war of 1814. Nepal lost the war and ceded, under the Treaty of Sugauli, substantive territories – nearly the whole of present day Uttarakhand – although it got some Terai regions back after helping the British out in 1857 revolt.

The boundary dispute dates to this time – the present contention is about the interpretation of this treaty.

The Kalapani Dispute

As per the Treaty of Sugauli, Nepal incurred heavy losses – Darjeeling and Sikkim in the east, the territories of Kumaon and Garhwal and most of the areas of the Terai region.

After 1816, the Mechi river became the Indo-Nepal boundary in the east and the Mahakali river (also referred to as Kali or Sharda river in India) became the western boundary between India and Nepal. The Treaty of Sugauli governs the present day geographical boundaries between India and Nepal. However, areas like Kalapani and Susta, among others, continue to be disputed.

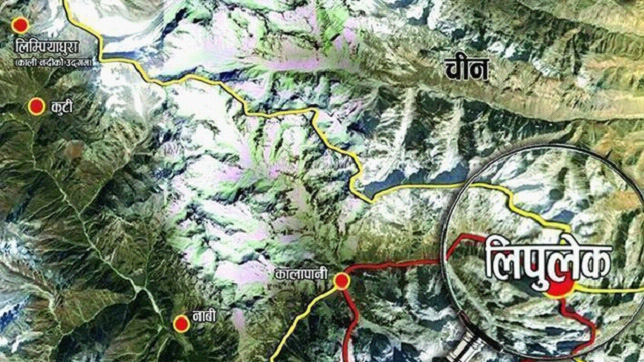

The present conflict centers around the dramatization of the Kalapani issue by Nepal through its diplomatic and political adventurism. Kalapani lies within the disputed trijuction of Limpiadhura, Lipulekh and Kalapani. India built an 80 km long road connecting Uttarakhand to Lipulekh, to get direct access to Tibet for the Kailash Mansarovar pilgrimage. This Lipulekh Pass was built as a result of 2015 agreement between India and China, with the latter recognizing India’s sovereignty over the region.

Nepal has raised the objection that the pass cuts through disputed territory of Kalapani, invoking the Treaty of Sugauli. According to the Treaty of Sugauli, all areas to the west of the Mahakali river are within India, while areas to the east of the river are retained by Nepal.

However, there were no accompanying maps exchanged with the Treaty of Sugauli which could show the exact location of the Mahakali river. Therefore, at present, there are competing claims – by India and Nepal – regarding where exactly the river Mahakali lies. Underlying this confusion is a changing of boundaries eastwards by the British which went uncontested by Nepal.

While in the years immediately following the Treaty of Sugauli till about 1857, the maps of British East India Company show the Mahakali river originating from Limpiadhura on the western side. However, from 1857 onwards, the British shifted their boundaries eastwards. Thus, the British era maps after 1857 began depicting the Mahakali river as lying to the east of the Kalapani area.

In the initial phase before 1857, the river being called Kali by the British was actually ‘Kuti’ or ‘Kuti Yangti’. From the late 19th century, Birtish maps began depicting a distinct Kali river (different from Kuti river) which originated at Lipulekh. Thus, with this shift in depiction of Kali, Nepal lost territory, since territories to the west of Kali river were to belong to India.

While these cartographic changes have been raised by Nepali government and intelligentsia after the fall of the monarchy in Nepal in 1990s, prior to that, even during the British era and in post-Independent India, Nepal did not raise this issue. Thus, the de facto control of Kalapani has come to be with India for more than a century and a half, and that has never posed any significant problem to Nepal, since India has been a guardian of Nepal’s security interests.

Nepal’s current position is that the Mahakali river originates from Limpiadhura and therefore, areas to the east of Limpiadhura – the entire trijunction within which Kalapani lies – belongs to Nepal. Nepal also maintains that Kalapani was offered only temporarily to India after the 1962 Indo-China war in order to help bolster Indian military position against China, and that Nepal’s newly issued maps are not new but have been in circulation till the 1950s. Nepal also conducted elections in the area in 1959 and collected land revenues from there till 1961 (Nayak, 2020).

This crux of the Nepali argument does not hold much substance in the light of the historical evidence and Indian arguments. Not only does India exercise actual control over Kalapani, this control has gone largely uncontested or mildly contested by Nepal since the last several decades. Indeed, India has argued that Nepal’s maps during the time of monarchy, since the last few decades, never showed the trijunction, including, Lipulekh as part of Nepal. To this, Nepal has given a completely bogus response viz. the monarchy did not depict these areas in Nepal’s maps so as to avoid antagonizing India and that these historical blunders of the monarchy are sought to be corrected by successive democratic governments in Nepal.

This is a completely whimsical and legally untenable position, since these internal political dynamics in Nepal cannot affect the legal positions on the boundary issues made with regard to India.

India’s position is that the river Mahakali originates in springs well below Lipulekh and that areas north of these springs have not been demarcated by the Treaty of Sugauli. India has also shown that administrative and revenue records dating to the 19th century show that Kalapani has always been administered as part of Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh district.

Changing Nature of Nepali Positions

The Nepali hostility towards India on the border issue has been motivated not by serious concerns over its territorial borders, but directly due to the inauguration of the era of Left-wing politics in a democratic system, whose mainstay in remaining relevant has been to unleash anti-India bashing from time-to-time.

Till the time of monarchy, while differences with India did exist, yet India was the main player in Nepali politics and Nepal’s interests inevitably coincided with India’s. Therefore, the border issue did not figure as a dispute between the two countries. However, with the fall of the monarchy Nepal has become antagonist towards India on the boundary issue as well as on other issues.

With the monarchy, issues could be easily resolved through informal channels like Shankaracharyas and there was no acrimony. India was in a dominant position in Nepal and no other country had entry.

The movement towards multi-party democracy since the 1990s has reduced the emphasis and importance given to symbolic cultural, religious and historical relationship between the two countries. Further, Nepal also, besides officially raising the border issue, began to demand a revision of the 1950 treaty, asserting that it did not treat Nepal as an equal partner.

The first time the border issue was raised officially as a boundary dispute was as late as 1998. In 1998, when Nepal formally raised the boundary issue with India, it effectively took advantage of the ill-conceived ‘Gujral Doctrine’ under which India managed to kill its own interests and agree to formally declare the Kalapani issue as a disputed problem between the two countries. In 2000, at Prime Ministerial level talks, it was decided that both sides would demarcate areas like Kalapani and Susta by 2002.

After the democratic transition in Nepal in 2005-06 which led to the inter-party agreement, introduction of secular, democratic Constitution and later the formal abolition of the monarchy, things became more challenging for India. The 12-point all-party agreement signed to usher multi-party system in Nepal, led to heavily emboldening the Maoists at the cost of others.

This course of events became inevitable and India reconciled with the new changes, as there were not too many options. Whether India wanted the monarchy or the Maoists or the democratic parties has been a moot question. Even when monarchy was active and King Birendra ruled, India had faced problems. After the Royal massacre of 2001, the new king Gyanendra had begun to tilt towards China and had even admitted – sometime after he was removed – that he had realised that his days were numbered as India won’t support him anymore.

Till 2001, when King Birendra was alive, the communist movement, while strong, did not have the popular support to challenge the King, as King Birendra was well-regarded and loved by people as an extremely popular, compassionate and strong leader. Neither did India have the capacity to challenge him covertly or otherwise. If Birendra had lived, then monarchy could not have been abolished.

However, it was the 2001 royal massacre – in which King Birendra, his wife and his children were murdered allegedly by his own son who later killed himself – that decisively tipped the scales against the monarchy and made the success of the communist movement inevitable. The new king – King Gyanendra – was extremely unpopular among the people due to his high-handed actions and personalized and notorious ways of his son. He was not someone that people could get inspired by or look up to. The conspiracy surrounding the massacre – common in Nepali politics – also tarnished the monarchy and added to Gyanendra’s extreme unpopularity. People’s perceptions around it were extremely strong and Gyanendra is still held in suspicion.

The new unpopularity of the monarchy – more than anything else – played into the hands of the communists and gave them success. India – a fence-sitter in these internal developments – had perceived that the communists were gaining success in exploiting the poverty and discontent among the people and that the monarchy’s time was limited. Therefore, it was more as an unavoidable strategy that India reconciled with the communists, knowing that the future belonged to them.

From being the sole and powerful actor in Nepal’s political scenario, India now shared the space with opening given to other countries. Europe and US gained a powerful presence, primarily through civil society organizations, NGOs, Churches etc. EU openly declared that ‘secularism’ has no meaning without a right to convert, while United Nations became an instrument for peddling the missionary agenda. China also got a powerful opening, especially in economic sectors. This is now visible very obviously in the political sphere, as China sets about unifying communist party factions in Nepal.

Indian policy also began to perceive Nepal through a security and political lens, and lost touch with emphasis on cultural aspect of India-Nepal ties. Currently, under Modi, India is again trying to emphasize cultural and historical links with Nepal and was successful to a great extent, but given the communist hostility in Nepal, this is proving to be a challenge.

In 2014, after Modi government came to power, efforts were made to break the logjam and improve relations with Nepal. The new government had already smoothly and successfully negotiated the exchange of land boundary enclaves with Bangladesh, and had assumed that with Nepal, situation would be much easier. Despite the fact that Indian diplomats followed up with Nepal many times to sort out these minor issues, there was no response from Nepal.

Between 2014 and 2018, Modi visited Nepal four times – more than he had visited any other South Asian country. In a break from the past Indian governmental approach, he made cultural and religious connection his mainstay, emphasizing the important role of the Terai belt in promoting historical exchanges between India and Nepal.

Modi devoted an entire exclusive visit to visiting holy places of pilgrimages in Nepal, such as Janakpur, Muktinath and Pashupatinath, being the first ever head of state to first land in Janakpur and then go to Kathmandu. He made sure to first offer prayers at the temple before addressing civic receptions. In his speeches, he dwelt mainly on spiritual relations between the two countries. His popularity during this visit was a resounding success among the people, even though some political elements in Nepal had attempted to abort it.

This attitude is continuing at present despite Nepali mischief. Despite the crude manner in which Oli has raked up the border issue and produced new maps, the Indian response has been calm. India has calmly rejected the Nepali position in a very balanced and dismissive way. India has also shown wideness in the present situation, as reflected in Rajnath Singh’s statement that Indo-Nepal relations are not only ‘historical and cultural’, but also ‘spiritual’ and that relations between India and Nepal cannot break.

BJP’s ideological parent, the RSS, as well as various priests and Shankaracharya (of Puri) in India, have called for maintaining good relations with the fellow Hindu country – in a marked contrast to the virulent anti-India street protests funded by the Leftists and missionaries in Nepal.

Thus, India considers the whole thing a non-issue. This lack of Indian response and action has made sure that this frivolous conspiracy backfired on Oli.

Nepali Tendency to Publicize Foreign Policy Issues

The question in the present issue is not about who the territory of Kalapani belongs to, but about how bilateral relations between India and Nepal came to be in such a dire situation. If we were to solely focus on the question of who the territory belongs to, then the Indian arguments are as strong and even stronger than any Nepali position. While historical evidence can be – and has been – twisted to support either side, the actual control has belonged to India, with the explicit official political and cartographic acceptance of Nepal. Even China – as a third party – has historically accepted India’s sovereignty over Kalapani.

Indian maps have not changed in their depiction of Kalapani over the last several decades, so there was no reason for Nepal to suddenly go to such extremes. Nepal first raised this issue anew in 2019 after India issued new maps in the wake of reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir in August 2019. The new maps that were issued in 2019 after the reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir had nothing to do with Nepal and continued to maintain the status quo with regard to Nepali borders. Yet, Nepal – following closely behind Pakistan and China – accused India of showing the disputed territory as part of India. Significantly, Nepal chose to escalate the issue in 2019 when Pakistan was already confronting India regarding the new maps, even though Nepal did not protest for so many years when the Indian maps depicted the exact same territorial boundaries.

Further, instead of following up with India seriously, Nepal yet again chose to make a complete public spectacle in May 2020 by cornering India when military confrontation with China was going on. The timing also coincided with KP Oli’s intense domestic troubles and the widening rift within Nepal ruling party. As a former Indian ambassador to Nepal has aptly pointed out, “My own experience has been that the Nepali side raises such issues for rhetorical purposes but is uninterested in following up through serious negotiations. This is what happened with Nepali demands for the revision of the India-Nepal Friendship Treaty. The Indian side agreed in 2001 to hold talks at the foreign secretary level to come up with a revised treaty — one that, in the Nepali eyes, would be more “equal” with reciprocal obligations and entitlements. Only one such round of talks has taken place. While I was in Nepal as ambassador, a request was made to put the issue on the agenda of the foreign secretary level talks held in 2003 but without any expectation of actual discussion. When we conveyed our readiness to have a substantive discussion on the treaty revision, the agenda item was dropped by the Nepali side. The purpose was to merely show that the Nepali side was taking up the issue seriously with India” (Saran, 2019).

The Nepali political double dealing is further brought home by the fact that Nepal did not protest in the past, even though the work on the Kailash Mansarovar road through the ‘disputed’ trijuction has been going on since 2008 and was scheduled to be completed in 2013, but was finally completed in April 2020. Nepal had many opportunities to protest in the last 12 years, but created a public nuisance only after the road was completed and inaugurated. Similarly, in 2015, a bilateral agreement was signed between India and China which referred to the role of Lipulekh pass as a trade route between India and Tibet. Then also, Nepal protested mildly and did not follow-up.

These events go on to show that Nepali hostility towards India is rooted not in any geostrategic logic, but in encouraging the play of pretences and appearances for the sake of domestic political consumption, and making India a conveninent whipping boy to divert attention from domestic troubles. The attempts to whip up anti-India sentiment have been made ever since Nepal entered the era of secular democracy in the middle of 1990s. The ideological communist baggage of major political parties in Nepal has further added to the compulsive acrimony periodically directed at India.

Indeed, the border issue assumed new, more acromonious proportions after the Maoists came to power in Nepal.

Prior to the 1990s when the Maoists came to power, the boundary question between India and Nepal was just limited to 62 square kilometers of area (marked in the dark brown in the picture above). After the Maoists came to power, this dispute widened to 335 square kilometers, covering the entire trijuction (The Darjeeling Chronicle, 2020).

This ideological baggage has been bolstered by the fact of the merger of the two major communist parties in Nepal in 2018, resulting in Oli leading the strongest government in almost 30 years, marginalizing the Nepali Congress and other opposition heavily and consolidating the communist hegemony over Nepal. However, as has been typical of Nepali politics, there is already intense instability within the government, with demands for Oli to step down, due to his mismanagement of domestic affairs. Prachanda now stands as being amongst his main rivals. Oli’s strength dramatically came down by two-thirds when Madhes-based parties withdrew their support in December 2019.

The trouble within Nepal has reached such proportions that even the unprecedented step taken by Oli to publish new maps, in a direct, needless and costly affront to India, could not do much to calm the rising tide against Oli. The usual political dividends that Oli had expected to garner in the wake of these unprecendented cartographic aggressions have not been forthcoming. Despite the unanimity with which the maps were approved in the Parliament, Oli could not unify the opposing factions across the political spectrum and could not consolidate his position.

The result is that Oli has been further reduced to publicly accusing the Indian ambassador in Nepal of joining hands with Prachanda, Nepali Congress and members of his own party to topple him. He has advanced these serious allegations without any evidence. His government has also banned Indian media (except Doordarshan) from broadcasting in the country, due to the low and base level through which it depicted Oli and the Chinese ambassador in Nepal. His government also passed a redundant bill that stipulates that foreign spouses (targeted at India) of Nepali citizens would have to wait seven years to get citizenship, in a targeted attack at Sarita Giri who dared to oppose Oli’s decision to issue new maps, leaving the Madhesis further disgruntled.

The Madheshi Factor that Dilutes all Manipulations

Oli’s haphazard comments and actions and the fact that they bear no fruit are indicative of the constraints on any Nepali dispensation. These constraints flow from internal demographic politics due to the significant presence of Madhesi community in Nepal. Madheshis are people of mainly Indian ancestry residing in the eastern areas of Nepal, belonging to the fertile Terai region. They are prominently distinguished from the people of the hilly or mountainous areas.

They share close relations – ‘roti-beti’ ties – livelihood and marriage ties with Indian people in the border states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Their political significance for Nepal is a key factor determining Nepali politics. The Terai region of Nepal, covering 33,999 square kilometers, constitutes nearly 23% of Nepal’s land area, and houses nearly half of Nepal’s population, with the country’s highest population density. Madhesis form nearly 1/3rd of the country’s population, and together, Tharus, Janjatis and Madhesis form nearly 51% of the population of Nepal.

Recently, the Madhes-focused parties combined together to form a single party viz. the Janata Samajvadi Party, Nepal. It has 32 members in Nepal’s lower House or Pratinidhi Sabha which has a total of 275 members. Thus, after the merger, the Madhes-backed party is the third largest party in Nepal’s lower House, after National Communist Party (NCP) with 173 members and Nepali Congress with 60 members. It has vocally protested against Oli’s new citizenship bill that targets foreigners and is seen to be targeting Indian-origin Madhesis’ demography and culture.

Since 2007, backed by India, they have been demanding greater rights, representation and autonomy, due to a deep suspicion of the ‘hill people’. In 2015, their power was on display as they imposed an economic blockade in the country – which disrupted the supply chains of essential commodities and stopped the flow of essential goods to Kathmandu – in order to protest against the controversial Constitution passed by the Nepali government. More than 50 people were killed in the blockade. While Nepal has accused India of imposing this blockade, the fact remains that Nepal had to compromise in front of Madhesi power, as they virtually held the country on tenterhooks.

Much like the present citizenship bill sought to be passed by Oli, the 2015 Constitution also discriminated against Madhesis on the basis of citizenship – in line with the Nepali government objective of exercising demographic control in the Terai region. The Constitution did not accord them equal representation in line with their sizeable population, and attempted to give more representation to people of mountainous regions. The demarcation of provincial boundaries was also protested as the Madhesi people’s area was sought to be reduced, as movement from India was sought to be controlled. All these steps were clearly seen by Madhesis as attempts to change their demography, reduce their power and political representation and take away their land.

The resultant blockade to protest the Constitution completely disrupted life in Nepal, as the country is surrounded by India on three sides and Indian transporters refused to enter Terai region. Thus, the Nepali government’s biggest check has been the demographically strong Indian-origin Madhesi people controlling the country’s most fertile plains – and this demographic factor is something that no country, not even China, can match, and something that Nepali government cannot afford to ignore.

Therefore, even if they want to, no Nepali government can afford to promulgate discriminatory policies that will disgruntle the Madhesis who form a sizeable population group, are close to India and control major supply chains and fertile tracts.

Conclusion

From the confused and harrowing manner in which Nepal, in the process of targeting India, has tied itself in knots, it is evident that serious discussion on territorial issues has been the last thing on Nepali agenda.

But the current controversy was less about the territorial issue and more about using the border dispute in an insincere bid to advance personalized ambitions by taking India for granted. The entire episode – which appears to be backfiring without any gains – was simply meant to create a domestic public spectacle through this issue. With India not dignifying this spectacle with any significant response except rejection of Nepali actions, the issue seems to have got Oli nowhere and his political problems have, indeed, only intensified further. As is the case with such half-baked plans, this one too seems to be backfiring on Oli.

Bibliography

Deccan Chronicle. (2019, November 18). Retrieved from https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/181119/indian-forces-must-withdraw-from-kalapani-nepal-pm-map-accurate-s.html

Dev, A. (2020, June 18). The Quint. Retrieved from https://www.thequint.com/videos/news-videos/explained-the-border-dispute-between-india-and-nepal

Ghimire, Y. (2020, June 24). The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/map-row-what-changed-in-india-nepal-ties-6470080/

Nayak, S. (2020). India and Nepal’s Kalapani Border Dispute: An Explainer. New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation.

Saran, S. (2019, November 27). The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/india-nepal-border-map-kalapani-6138381/

Singh, M. (2020, May 25). The Print. Retrieved from https://theprint.in/opinion/gen-naravanes-insensitive-remark-undermined-40-battalions-of-nepalis-in-indian-army/428218/

Singh, S. K. (2019, September 2). Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-raw-threw-out-monarchy-in-nepal-reveals-ex-spl-director-2786770

The Darjeeling Chronicle. (2020, May 21). Retrieved from https://thedarjeelingchronicle.com/india-nepal-border-controversy/