Agriculture has become a complex sector in India. It is facing crises at multiple levels, which will exacerbate the food quality and security crisis, the environmental crisis and the farm crisis being faced by us.

In addition, the agrarian sector in India is also often at the root of numerous other socio-economic crises the country has seen. The most prominent examples are the struggle over the Land Acquisition Act, the uprisings by caste-based communities dependent on the stagnating agricultural sector, such as the Jat agitation in Haryana and the Maratha agitation in Maharashtra. The Dalit agitation is also assuming economic proportions, as the causes of unrest among Dalits are increasingly being linked to their deprivation of their land titles.

In terms of environmental factors, the agricultural sector is the worst affected by the current environmental crisis facing the country – be it the crisis of water, climate change or land degradation. Last year we faced four back-to-back droughts for the first time in over a century, leading to a persistent decline in food-grain production, which, if not remedied will hurtle us back into the era of severe food shortage.

Major Issues in Indian Agriculture

The major issues that implicate the agricultural sector include:

- Water crisis in the country.

- The crisis of climate change, where crops are being experimented upon to make agriculture more “climate-resilient”.

- Land and soil degradation.

- Food crisis, due to the use of chemicals and fertilizers, deteriorating the quality of food.

- Socio-economic dimensions, with the rise of several agitations by social groups dependent on farming, and, inter-state water disputes.

Ground water depletion has become an especially critical area of concern in Indian agriculture.

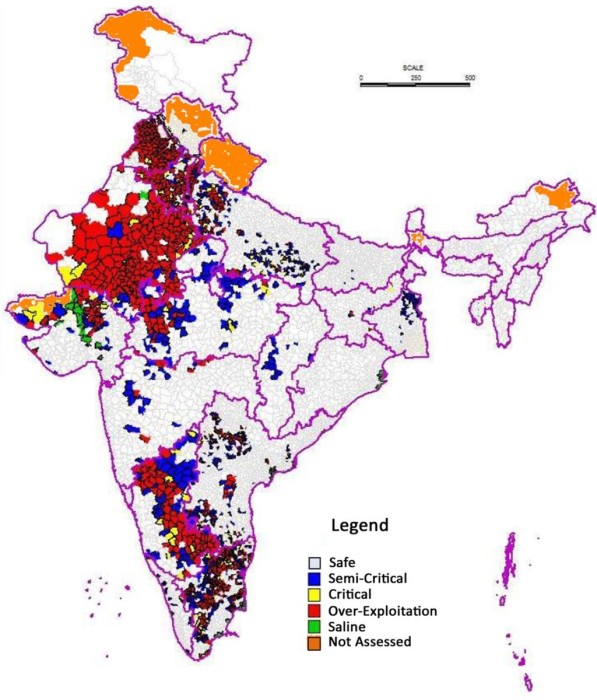

As can be seen from the map1 below, there are five types of ground water assessment units viz. safe, semi-critical, critical, over-exploited and saline. A substantial portion of our ground water units are marked as over-exploited (the units marked in red).

This means that we are exhausting our ground water reserves faster than we think. Ground water is a critical component of agriculture, as it is used for irrigation. However, our agricultural practices have become so intensive that a major part of our ground water is being diverted for irrigation.

This has, in recent times, given rise to another big issue in form of inter-state water disputes and the drinking water crisis. For instance, in the dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu over the Cauvery river waters sharing, the issue is the conflict between sharing of water for drinking water purposes and irrigation purposes.

With around 60% of Indian agriculture being sustained by groundwater, the diversion of water for irrigation purposes has led to spectacular ground and surface water depletion since the last several years.

The spectacle of the Marathawad region, this year, is something that nobody is able to decode. While the region suffered its worst drought this year, it is now reeling under excess rainfall. Kerala has been declared as the state worst affected by drought this year, while water conflicts are producing social violence across states like Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Goa, Odisha, Jharkhand, Kerala and Puducherry. All of these conflicts boil down to the agricultural sector – the drinking water scarcity and inability to irrigate fields.

Another area of concern has been mounting coastal and soil erosion which is further impacting the crops. Soil degradation is approaching worrisome levels in most parts of India, with 50% of total land and 66 % of cultivated land being degraded – the highest amongst Asia Pacific countries.

Thus, due to a combination of environmental factors, we are facing our worst agrarian crisis, with no solution in sight. And this is when we have not even begun talking about the issues of deteriorating food quality and the use of chemicals in our food.

A Chequered History: Green Revolution

The dire condition of agriculture in India can be traced to the Green Revolution, where inputs like water and fertilizers were used relentlessly to boost farm production. The Green Revolution was initiated by the government in the backdrop of the food crisis that gripped the country during the 1960s, when we were importing massive amount of food from the US. It was an attempt to become self-sufficient in food grain production. As a result, traditional farming methods gave way to high-yield seeds, fertilizers and pesticides.2 It was based on a model of seed-fertilizer-irrigation, where high-yielding varieties of seeds were used to enhance production and productivity, and the loss of soil nutrients was sought to be made up through the use of chemicals like phosphorous potash and nitrates.3

The problem, for us, began when we started viewing our critical means of livelihoods as ways to enhance productivity, use technology and derive maximum benefits for ourselves. Thus, very soon we converted our food grain production units into surplus granaries to be used for exporting food grains and began to earn foreign exchange, thereby making a rich class of farmers.

Our fertilizer consumption also kept increasing, going up from less than 1 million tons of total nutrients in the mid-sixties to almost 25.6 million tons in 2014, with fertilizers alone enhancing our agricultural growth by about 50 per cent,4 showing that our agricultural growth and the so-called golden age of Green Revolution came at a dire cost of bad consumption of fertilizers, which proved to be fatal to the quality of our soil and crops and water.

In practice, this was given encouragement by skewed policy choices – with, for example, the government giving incentives, during Green Revolution, to extract groundwater for irrigation and promotion of deep-water extraction techniques which resulted in further wastage and extraction of water – and unbridled greed for more and more.

The excessive use of harmful technologies like fertilizers are giving us the impression that we are producing sufficient quantity of food. But, in reality, this is an illusion. We are living in an age of severe food scarcity, and nothing has changed from the situation in 1960s. Sustaining our agricultural production through the use of fertilizers has deteriorated our soil and crop health and is poised to have a slow, cancerous impact on our health too.

So, minus the chemicals, we are living in an age of scarcity. According to the latest report of the Lok Sabha Standing Committee on Agriculture, “the country will require about 300 MTa of food grains by 2025 to feed its teeming millions. This would necessitate use of about 45 MT of nutrients. While about 6-8 MT of nutrients could be supplied through existing organic sources, the rest has to come from chemical fertilizers.”5

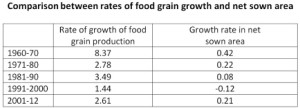

The table above shows that while there has been a great increase in the rate of food grain production in the country, there has been negligible progress in the net sown area. Since there are limitations to expanding the net sown area, there has been an increasing recourse to options that can give greater crop yields per hectare, enhancing the use of chemicals and fertilizers.

Moreover, the use of harmful non-organic fertilizers is causing environmental concerns like greenhouse gas emissions and pollution of water bodies. There is increasing pollution of ground water with nitrates due to use of nitrogenous fertilizers. Fertilizers also contribute about 77% of the total nitrous oxide emissions from soils, and, nitrous oxide has a global warming potential which is 298 times more than that of carbon dioxide over a 100 year period.6

The result of the policy choices of Green Revolution is that major agricultural producing states like Punjab and Haryana, as well as the south-eastern parts of the country, are no longer able to sustain their agrarian economies, and the use of advanced, but unsustainable technology is worsening farm debts. Added to this is the corruption, with numerous middlemen preventing the farmers from getting the right procurement price, even though the benchmark is set by the government. This has agitated many farmers, since the BJP had promised to set MSP to ensure 50% profit margin over the cost of production.

From Green Revolution, we have been steadily moving towards a system of resource-intensive agriculture – particularly with regard to wheat, sugarcane and rice – which has led to the widespread use of commercial agrochemicals, leading to a build-up of heavy metals in the soil – these are hazardous to people’s health and are well-known carcinogens.

These practices have all extracted all nutrients from the soil – the number of elements deficient in Indian soils increased from one in 1950 to nine in 2005-06.

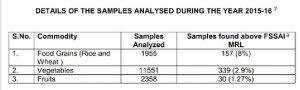

The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare has started a central sector scheme, “Monitoring of Pesticide Residues at National level” under which samples of food commodities are collected and analysed for the presence of pesticide residues, with reference to MRL (Maximum Residue Levels).

It is clear that we have significantly increased the levels of pesticides found in our commodities, especially in food grains.

And, now, the problem has become much worse. For, now we are destroying the soil and our food systems in the name of ‘environment’ – and the government has fallen prey to this rhetoric. All the focus is on showing that we are meeting certain environmental “targets”. In the process, what we actually do is to make profit and destroy our agriculture and environment further.

The Current Scenario: No Lessons Learnt from the Past

Have we learned any lessons from the persistent stagnant state of Indian agriculture? Going by the current worsening crisis in this sector, the answer is clearly no. We are caught in a vicious trap, wherein the worsening impacts of environment on agriculture and the persistent motive of money-making is leading us to adopt dangerous, albeit “profitable” solutions, that will destroy our health and worsen the food crisis in the country, such as the so-called climate resilient crop and plant varieties.

In terms of larger problems created directly by us, we have major policy stumblings, with the three main global agri-company mergers set to consolidate the global agricultural markets and lead to long-term impact on the nature of products that we will consume. This means there will now be greater threat from GM food products and less transparency as key players monopolize the agricultural markets.

Deteriorating Seed and Crop Quality

The GM threat is already being faced in India, with the latest controversial introduction of GM Mustard by the government. In an age of technology and globalization, as the agricultural sector becomes more and more mechanized, such introductions will become common.

Results of Bt Cotton that is being cultivated in India, since 2002, and now covers 90% of land area under cotton cultivation, also shows that pests become resistant to GM cotton variety over time and that it is also ineffective against other major cotton pests such as mealy bug and white fly. The government has become entirely commercially-minded when it comes to agriculture – it is also pushing for genetically modified substitutes to target nutrition deficiency, such as Golden Rice for Vitamin A.

Despite the ill-effects of GM technology, the government, in 2014, took the controversial decision of introducing field trials of 13 GM crops, which was widely opposed.

India’s policy is giving major thrust to various crop management techniques for the purpose of developing:

- Genetically modified crops, in view of the shrinking arable land.

- Developing climate resilient crops.

- Diverse cropping systems tolerant to various risks and diseases.

The government, since 2014, integrating existing seed policies, created a new “Sub Mission on Seed and Planting Material” under a new central scheme where the objective is “to develop/strengthen seed sector and to enhance production and multiplication of high yielding certified/ quality seeds of all agricultural crops and making it available to the farmers at affordable prices and also place an effective system for protection of plant varieties, rights of farmers and plant breeders to encourage development of new varieties of plants.”8

This has given a major push to hybrid and GM crops.

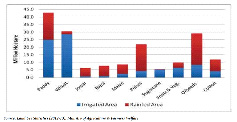

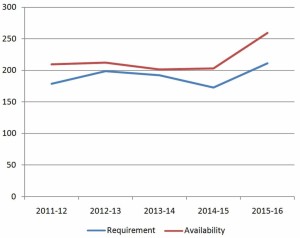

If we decode the above table, it will be clear that the government is giving a clear policy push to hybrid seeds:

For the total number of hybrid seeds pushed over the years, there is a clear trend wherein the demand for hybrid seeds has always been less than their availability by the government. Moreover, since 2014-15, there has been a sharp increase in the availability of such seeds, even though their requirement has not gone up commensurately, even when we count for the efforts being made by the government to create positive sentiments about these seeds.

A total of 81 high-yielding varieties of crops and hybrids have been introduced. These include 19 varieties of rice, 12 of wheat, 6 of barley, 11 (hybrids) of maize, 9 millets, 7 oilseeds, 11 pulses (including 2 of green gram, 2 each of pigeon pea and field pea and 1 each of black gram, chickpea, lentil, horse gram and cowpea), 2 of sugarcane and 4 varieties and 1 hybrid of forage crops.

Disease resistant H-369 Hybrid tomato

Kufri Lalit Hybrid Potato (yield 25.5 tonne per hectare)

These varieties of tomatoes, potatoes, mangoes, and other grains, fruits and vegetables are high-yielding and disease-resistant. But they have severe adverse health effects. Thus, they only serve to create the illusion that there is no scarcity of food. But what is actually being served on our plates spells a death knell for us.

Future Directions

Agriculture has become an entirely mechanized sector. There is little focus on quality and a lot on how to make profit out of it, and how to keep our present cycle of greed going. Striking international and regional agreements, we import technology that may devastate our livelihoods and increase the ambition, greed and corruption in the system. This is demonstrated amply in the recent agreement that India signed with Russia at the recent BRICS summit in Goa, where the two countries agreed to set-up irradiation centers in India, for treating the farm produce. Certifications from IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) are cited to show that the technology would be ‘absolutely safe’. Ostensibly, the purpose is to subject the agricultural produce to nuclear radiation in order to finish off the frequent pests that assail them, so as to increase their storage and shelf-life.

The government is not realizing that the agrarian crisis has deep-rooted implications, and, is therefore targeting all the wrong solutions. It is looking towards the kind of high-level technological innovations like GM crops and nuclear treatment which will prove to be fatal and piecemeal measures like setting up new irrigation facilities, installing projects for ground water restoration, conservation of soil fertility and doubling farmers’ income by 2022 and diversification of rural economy.

When we talk about these short-term fixes, the devil lies in the detail. For example, while there is lot of discussion on increasing total and per hectare food production, there is little focus on the quality of food. This means that we end up talking about promoting high-yielding crop varieties and further use of agrochemicals – all of which sounds very fashionable and technical on paper, but will be disastrous for health. The result is that instead of perishing of food scarcity now, we will die a slow, torturous death. For, with limited availability of fertile land to cultivate food, the only alternative is to increase per hectare productivity by these dangerous, short-term methods.

The government seems to be moving in a populist direction on this issue. It is concerned mainly with doubling farm incomes by 2022, for which it can take any measures, since actual food quality will take less priority. In a recent development, the Niti Aayog proposed a strategy to liberalize the agricultural sector by eliminating the role of middle-men and reforming various laws, and, digitizing the agricultural market, to make the markets directly accessible to the farmers. In this area the government is working positively in signaling the right policy intention, but it is the motive of commercialization and profit-making that needs to be kept out to save our bodies and souls.

References:

- Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare. 2016. State of Indian Agriculture 2015-16. New Delhi: Ministry of Agriculture and Famers Welfare

- Lok Sabha. 2016. “Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 289.” Lok Sabha, July 19

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare. 2016. State of Indian Agriculture 2015-16. New Delhi: Ministry of Agriculture and Famers Welfare

- Ibid.