III. The Post-Independence Relations Between India and China from 1947 to the Present

A. The Period from 1947 to 1954

B. The Period from 1955 to 1961

An Overview of the Period

During the early nineteen-fifties – the period marked by an increasing Chinese military superiority over India – both countries were friendly and cordial to each other and the Chinese did not want to disturb this because they found in Nehru an important champion of their case in international forums and thus a great help in their control of Tibet. Therefore, they deliberately chose to be vague about the border issues with India, a discussion of which, they felt, might come in the way of their cozy relations with her. They avoided putting out any territorial claims either in writing or orally. When they did so, it was done only on the basis of their printed maps. Thus, the Chinese claim in the Eastern Sector appeared only as a line on their maps dipping at points about 100 miles south of the McMahon Line. Chou En-Lai in his talks with Nehru in 1954 and 1956 treated the Chinese maps not as representing Chinese “claims” but as old maps handed down from previous mainland regimes which had “not yet” been corrected – thus cleverly avoiding anything that may create unpleasantness in warm relations between the two countries. The period of cooling in warm Sino-Indian relations began in 1958 when the border issue surfaced for the first time due to serious differences over the ownership of the Aksai Chin plain where the Chinese had completed the construction of a highway by the end of 1957.

The Aksai Chin plain was crucially important to China at that time as it provided the only link from the west between China (Sinkiang) and Tibet over which they were still in the process of securing full control. To agree to give it back was viewed by them as a major defeat and humiliation, especially when, according to them, the border had never been officially demarcated and in their unsuccessful efforts to do so the British had officially proposed to China a line – called McDonald Cartier Line – in 1899 which clearly put the Aksai Chin plain on their side. Also, the Chinese may have felt, not unreasonably, that just as Indian forces had gradually moved up into NEFA in the early 1950s and established their military presence in the area belonging, according to them, to Tibet, they could also be with equal justification move gradually into the Aksai Chin area to establish their military presence there. As a quid-pro-quo Chou En-Lai had urged Indian leaders during 1959 and 1960-61 to accept the Chinese claims (an area of about 30,000 square kilometers) in the Western Sector in exchange for their (the Chinese) acceptance of the Indian position (an area of approximately 90,000 square kilometers) in the Eastern Sector. Not only this, but – as both sides agreed – the quality of the land in NEFA was much better than that of the Aksai Chin which was of practically no economic or strategic value to India. From his utterances in public and the Parliament, Nehru, by the end of 1959, seemed to be preparing the Indian people for the exchange of Aksai Chin to China for Indian ownership of NEFA, but this was prevented because of the strong opposition from some prominent leaders in the “Opposition” and even within his own Congress Party.

From the available Chinese records of the period it is clear that the then top Chinese leadership valued highly the traditional warm historical relations of their country with India extending over a period of at least two millenniums and did not want to spoil them if at all possible. Besides this, in their eyes, Nehru enjoyed a very high position among the “Third World” countries, whose opinion the Chinese could not afford to neglect. Not only all this, even within their own communist movement, the Chinese leaders were warned by Khrushchev and the Indian communist leaders about the grave risks involved in pushing (by their policies) Nehru over the edge into the so called “Imperialist Camp” of the U.S. and its allies. The Chinese tried very hard, particularly after the unfortunate border clashes of late 1959 which brought them bad name, to arrive at some kind of peaceful accommodation with India on the border problem. To demonstrate in the eyes of the neutral world their earnestness and flexibility on border disputes with their neighbours they speedily signed agreements with Burma, Nepal, Mongolia and initiated negotiations with Pakistan – even accepting less favorable terms.

The enormous pressure of the Indian public opinion expressed through the Press and the Opposition in Parliament and felt not just by some senior leaders in the Congress Party but also by the bureaucracy in the MEA and the Army made it virtually impossible for Nehru to adopt a flexible attitude in his negotiations with the Chinese during the years 1960 and 1961. The public pressure at that juncture was not illegitimate given the inaccurate and one-sided information that people had about the whole issue of the validity of Indian claims vis-à-vis those of the Chinese in the Eastern and Western Sectors. Having made public the contents of his September 26, 1959 letter to Chou and later on, the official report of the border talks between the officials of the two countries during the latter half of 1960, Nehru found himself locked into a situation from which he could not have gotten out except by frankly admitting before his people the truth about the 1899 proposal of the British to the Chinese and the unilateral change of Indian maps in July 1954. Nehru found himself unable, psychologically, to take this later stand, for, he could not have foreseen what was in store for him and his beloved people if he followed the course he found himself impelled to follow under the then prevailing circumstances. Much less could he have foreseen how the second course – more transparent and wiser – would have favourably altered the whole course of national happenings during the 1960s and thereafter. However, as things stood, in the latter half of 1961, a most unreasonable and foolish – being based on a gross miscalculation of Indian defence preparedness vis-à-vis that of the Chinese – Forward Policy was pursued by the Indian government which led to the humiliating defeat of 1962.

(i) The Period from 1955 to 1958: The Years of Panchsheel Euphoria to the Beginning of the Cooling in Mutual Relations

(a) The Bandung Conference

In the year 1955 the euphoria of “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai” continued unabated. After his return from China in November, 1954, Nehru started making preparations for the forthcoming Bandung Conference to be held in Bandung, Indonesia. This first large-scale Afro-Asian Conference was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent. It was sponsored by Indonesia, Burma, Pakistan, Ceylon and India and took place during the week of April 18-24, 1955. Having just returned from his China visit, Nehru’s enthusiasm for China was again exhibited at this Conference when he became the main sponsorer of Chou En-Lai to this conference in spite of reservations from some countries.

(b) The Aksai Chin Road

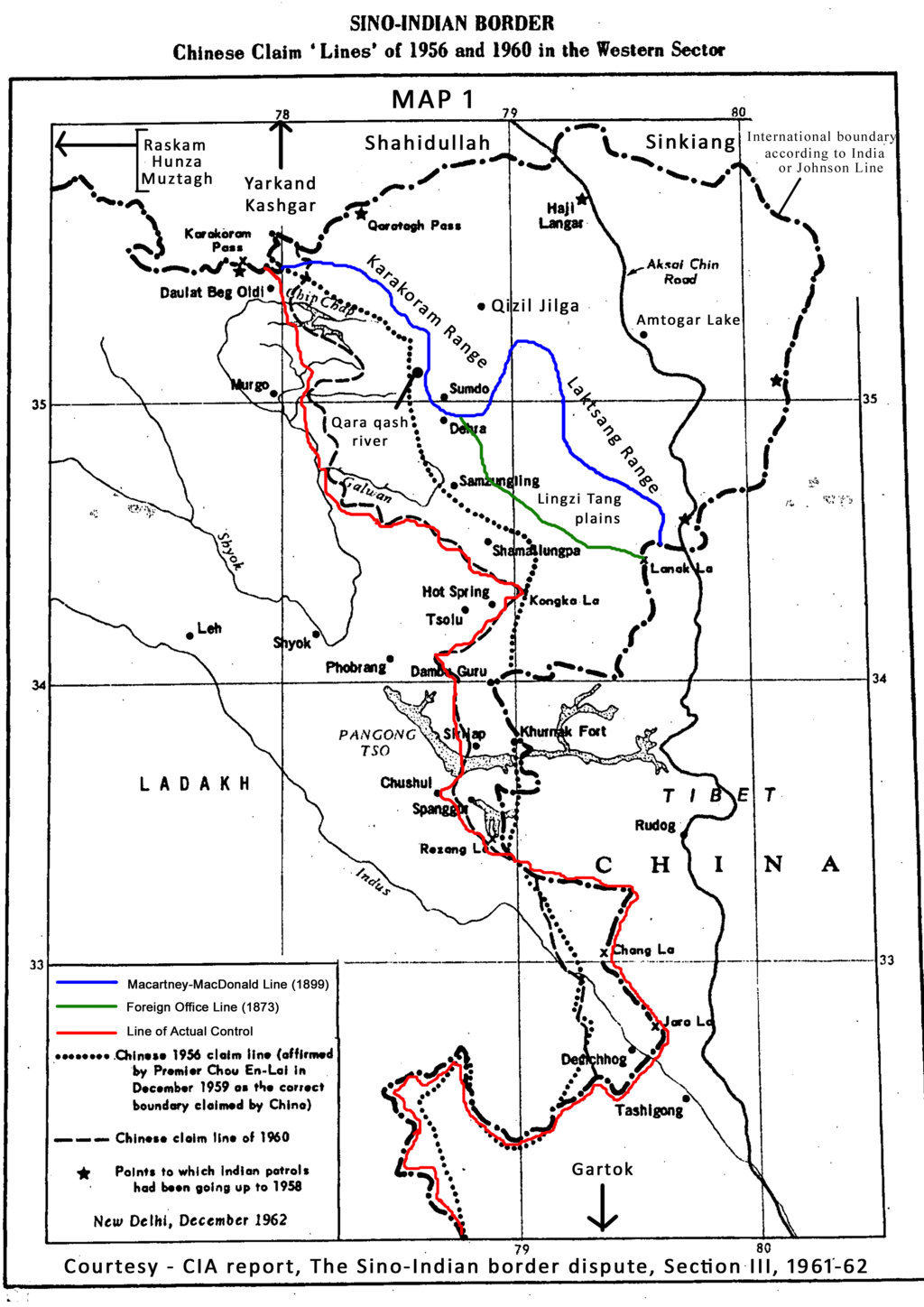

“The Official Report of 1962 War states: ‘The Preliminary survey work on the planned Tibet-Sinkiang road having been completed by mid-1950’s, China started constructing motorable road in summer 1955. The highway ran over 160 km across the Aksai Chin region of north-east Ladakh. It was completed in the second half of 1957. Arterial roads connecting the highway with Tibet were also laid. On 6 October 1957, the Sinkiang-Tibet road (Map 1) was formally opened with a ceremony in Gartok and twelve trucks on a trial run from Yarkand reached Gartok. In January 1958, the China News Agency reported that the Sinkiang-Tibet highway had been opened two months earlier and the road was being fully utilized.”1

The Government of India has never acknowledged that it had information about this road as early as 1955. On October 6, 1957 a Chinese newspaper Kuang-ming jih-pao reported the completion of the Sinkiang-Tibet road – the highest highway in the world. It took almost two more years for the news to become public when in August 1959 Nehru informed the Indian Parliament that the Sinkiang-Tibet highway was built through Ladakh.

“…it was not until April 1958 that Nehru decided to dispatch two military reconnaissance patrols to determine the alignment and check on Chinese military post locations in the Aksai Plain. Nehru’s personal guidance to the patrols included the order to capture and bring back to Leh any ‘small’ group of Chinese encountered and, if a ‘large’ force were encountered, to inform the Chinese troops that they were in Indian territory and ‘ask them to leave’. The Indian patrols started out in June; one was ‘detained’ by the Chinese on the road in early September 1958. Peiping’s 3 November 1958 note to New Delhi, which stated that the patrol members would be released, insisted that both patrols had ‘clearly intruded into Chinese territory’. The Indians took this statement as a formal claim to the Aksai Plain, noting on 8 November that it is ‘now clear that the Chinese Government also claims this area as their territory.’ Thus by the time the full meaning of the Chinese gradual advance into the Aksai Plain had been borne home to him, Nehru was confronted by a military fait accompli: Chinese forces exercised actual control along the road.”2

“Chinese claims in late 1958 regarding the Sinkiang-Tibet road (and the territory which it traversed) and the capture of the Indian patrol on the road did not lead immediately to general public awareness of the border dispute or the embitterment of the Chou-Nehru personal relationship. These claims did not breach in this relationship but rather contributed to a gradual cooling of attitudes already occurring. Signs that Chinese and Indian relations had begun to cool appeared earlier in 1958, particularly when the Chinese in summer postponed indefinitely Nehru’s proposed trip to Tibet and in fall waited three weeks before granting visas to him and his party to cross a small portion of Tibet – where they were subsequently snubbed by the Chinese – on their way to Bhutan. Nehru, however, still refrained from making public attacks on such Chinese actions – including minor border incursions – which would stir up Indian opinion and damage his relationship with Chou. Despite the formal protest (18 October 1958) to Peiping regarding the capture of the Indian patrol on the road, Nehru was reliably reported at the time anxious to keep this and other recent border incidents from public knowledge.”3

The Nehru government officially complained to Beijing on 18 October in an Informal Note given to the Chinese Ambassador in New Delhi on that day. The Note stated, “The attention of the Government of India has been drawn to the fact that a motor road has been constructed by the Government of the People’s Republic of China across the eastern part of the Ladakh region of the Jammu Kashmir States which is part of India. This road seems to form part of the Chinese road known as Yehchang-Gartok or Sinkiang-Tibet highway, the completion of which was announced in September, 1957.

The road enters Indian territory just east of Sarigh Jilgnang, runs north-west to Amtogar and striking the western bank of the Amtogar lake runs north-west through Yangpa, Khitai Dawan and Haji Langer (See Map 1) which are all in indisputable Indian territory. Near the Amtogar Lake several branch tracks have also been made motorable….”4

The Note continued and went on to accuse that the Chinese officials, workers and travellers used the road to enter Indian territory without proper travel documents and visas. “In conclusion, the Note stated: ‘the Government of India are anxious to settle these petty frontier disputes so that the friendly relations between the two countries may not suffer. The Government of India would therefore be glad for an early reply from the Chinese Government.’”5

(c) The Euphoria Years in Sino-Indian Relations: The Years 1956-57

“Chou En-Lai visited India for the second time in November 28, 1956 on a goodwill mission. Besides discussing many international issues with Nehru, he referred to the border between India and China, and it was decided that while there were no dispute regarding the border, there were certain petty problems which should be settled amicably by the representatives of the two Governments. In an address to members of Indian Parliament on November 29, Chou referred to the long unbroken record of Sino-Indian friendship for several thousand years and hoped for the continuation of this peaceful tradition in future. Chou surprised the crowd when he ended his speech with the words ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai’ and ‘Jai-Hind’ (long live India).

In Calcutta during a press conference, when a reporter asked Chou whether he would like to send a message or any proposal for the US Government through Nehru who was about to visit the US. Chou replied Prime Minister Nehru is a messenger of peace, no matter where he goes, no matter whom he meets; he would discuss matters concerning world peace. If Nehru happens to discuss the problem of Sino-US relations with President Eisenhower, in that case we are sure that he would raise the view that would be beneficial for improving Sino-US relations.”6

“A trade agreement signed between India and China in October 1954 was renewed in 1956. This agreement led to a steep rise in trade between the two countries. The New China News Agency reported that trade between India and China had increased steadily in the past fifteen months. India’s exports to China had increased nine-fold while imports from China had increased three and a half times over the pre-agreement period. In 1956, Indian visitors to China included a Parliamentary delegation, an agricultural delegation to take stock of Chinese techniques, and another agricultural delegation to study Chinese cooperatives. Military delegations were also exchanged.”7

“The Chinese Prime Minister Chou En-Lai after visiting the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary and Afghanistan yet again landed in New Delhi on January 24, 1957. He held three hour long discussions with Nehru. Though Chou informed the reporters that he had came to India just to hold private discussions with Nehru, however, it is obvious that issues such as increased unrest at the Sino-Indian borders, the inclination shown by the Dalai Lama to stay on in India, and to some extent to gauge the Indian reaction prior to his Nepal visit were in his mind. Chou also drew India’s attention towards Kalimpong that was being used by America and other countries as a centre of espionage and sabotage against Tibet. Nehru expressed sincerity and assured Chou En-Lai that the Dalai and Panchen would return to Tibet through same route they had followed for their journey to India. As regards activities of espionage in Kalimpong, India would follow a cautious approach.

The Indian Vice President S. Radhakrishnan visited China from September 18 to 28, 1957. Both sides as usual harped on the issues of ‘peaceful coexistence’ and ‘world peace’ at the time when real trouble was brewing on the boundary. Mao in a banquet held in the honour of his Indian guest on September 19 spoke, ‘Our two people are each building their own state and striving for world peace. For the sake of these common goals, our two countries are carrying on a close and friendly cooperation. The uniting together of one billion people of China and India constitute a great force and is guarantee for Asian and world peace’. Mao also thanked India for the support it had extended to China on various international issues and expressed no doubt about India assuming an ever-important role in the world. Radhakrishnan on his part reiterated Indian position of sponsoring China at every international forum by saying that without any suggestion and guidance from China it would be difficult for us to solve the problems concerning Asia. Contacts were also developed between the two nations outside the pale of governmental cooperation, at the cultural and commercial levels. There was a steady flow of study teams, military missions and educational delegations between the two countries. India-China Friendship Associations were also established in both the countries to promote better understanding and relations.”8

At the end of 1956, when Dalai Lama (and Panchen Lama) visited India on the invitation of the Indian Government to participate in the 2500th birth anniversary of Lord Buddha, he was invariably accompanied everywhere by the Chinese officials which indicated his strained relations with the Chinese. During his visit, the Dalai Lama had expressed his wish not to return to the communist dominated Tibet. The Chinese were not unaware of Dalai Lama’s unhappiness with them and, therefore, did not want him to visit India. He was allowed to come to India mainly because of New Delhi’s pressing the invitation to him and his pressing for the acceptance of it. The November 1956 visit of Chou En-Lai was partly prompted by China’s concern over Dalai Lama’s visit to India. It is reported that the Chinese Prime Minister assured Nehru that the Chinese Government would respect Tibet’s autonomy and Nehru conveyed this assurance to Dalai Lama and persuaded him to return to Tibet. Nehru also promised that he himself would visit Tibet after some time. Side by side with all the above, some minor unpleasant incidents and exchanges had started taking place on both sides of the border between the two countries by the end of 1957.

(d) The Year 1958

In June 1958, the Chinese occupied Kurnak (Map 1) in Ladakh by crossing into the Indian claimed territory and gradually established their posts at Spanggur and Diagra. This led to exchange of notes through diplomatic channels and the process was further quickened with the publication in a Chinese magazine – China Pictorial – in July 1958 of a map which depicted a large area – about 130,000 square kilometres – of India-claimed area mostly in Western and Eastern Sectors, as Chinese territory. On August 21, 1958, the Indian government delivered a protest note to the Counsellor of China on this matter pointing out that sufficient time had elapsed by then for the Chinese government to correct their old maps. When further trouble brewed on the frontier, the Government of India delivered a protest note to the Chinese ambassador in India on 18th October, 1958. China questioned India’s contention in a strongly worded note of November 31st, 1958.

Further exchange of letters took place in November and December 1958. Finally in his January 23rd, 1959 letter Chou En-Lai repudiated Indian claim of settled traditional boundary and pointed out to Nehru that Sino-Indian border had never been formally delimited. This letter of Chou En-Lai for the first time brought it home to Nehru that a border dispute did exist between India and China. Chou also questioned the legality of McMahon Line which he labelled as the product of the expansionist British imperialism. However, all this, concluded the Chinese Prime Minister, “absolutely should not affect the development of Sino-Indian friendly relations”. Thus the small border clashes beginning from mid and late fifties, especially in the Western Sector of Ladakh where the Chinese had constructed a road linking Sinkiang to Tibet across the Aksai Chin plateau and the claims and counter claims in formal communications beginning 1958 set into motion a process of deterioration into Sino-Indian relations which turned into open hostilities with an uprising in Tibet and the flight of Dalai Lama to India in 1959 which unduly clouded the view of the top Chinese leadership and led them to entertain an entirely false view of Nehru’s motives who, even in changed circumstances of 1959 – in which an entire sympathy with the Tibetan case was witnessed in Indian media and people in general – carefully struck to his earlier perception of India’s correct poise on the Tibetan problem and, in our view, the events of past fifty years have proved him right.

(ii) A crucial year in Sino-Indian Relations – the Tibetan Uprising and the Souring of Sino-Indian Relation

(a) The Tibetan Uprising, The Flight of Dalai Lama to India and the Pernicious misconception of the Chinese Leadership About India’s Role in Tibet

In 1951, a seventeen point agreement between the People’s Republic of China and representatives of the Dalai Lama was put into effect. Socialist reforms in China such as redistribution of land which were started in 1954 were delayed in Tibet proper. However, eastern Kham and Amdo (western Sichuan and Qinghai provinces in the Chinese administrative hierarchy) which were outside the administration of the Tibetan government in Lhasa were treated more like other Chinese provinces, with land redistribution implemented in full force. The Khampas and nomads of Amdo traditionally owned their own land. Due to this factor armed resistance broke out in Amdo and eastern Kham in June 1956. By 1957, Kham was in chaos. People’s Liberation Army reprisals against Khampa resistance fighters such as the Chushi Gangdruk became increasingly brutal.

Meanwhile, Lhasa continued to abide by the seventeen point agreement and sent a delegation to Kham to quell the rebellion. After speaking with the rebel leaders, the delegation instead joined the rebellion. Kham leaders contacted the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), but the CIA under President Dwight D. Eisenhower insisted it required an official request from Lhasa to support the rebels. Lhasa did not act. Eventually, the CIA began to provide covert support for the rebellion without a word from Lhasa. By then the rebellion had spread to Lhasa which was filled with refugees from Amdo and Kham. Opposition to the Chinese presence in Tibet grew within the city of Lhasa.

On 1 March 1959, an unusual invitation to attend a theatrical performance at the Chinese military headquarters outside Lhasa was extended to the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama initially postponed the meeting, but the date was eventually set for 10 March.

According to historian Tsering Shakya, the Chinese government was pressuring the Dalai Lama to attend the National People’s Congress in April 1959, in order to repair China’s image in relation to the ethnic minorities after the Khampa’s rebellion. On 7 February 1959, a significant day on the Tibetan calendar, the Dalai Lama attended a religious dance, after which the acting representative in Tibet, Tan Guansan, offered the Dalai Lama a chance to see a performance from a dance troupe native to Lhasa at the Norbulingka. According to the Dalai Lama’s memoirs, the invitation came from Chinese General Chiang Chin-wu, who proposed that the performance be held at the Chinese military headquarters; the Dalai Lama states that he agreed. The planned performance date of 10 March was only finalized 5 days beforehand, i.e. on 5 March. Neither the Kashag (governing council of Tibet ) nor the Dalai Lama’s bodyguards were informed of the Dalai Lama’s plans until Chinese officials briefed them on 9 March, one day before the performance was scheduled, and insisted that they would handle the Dalai Lama’s security. The Dalai Lama’s memoirs state that on 9 March the Chinese told his chief bodyguard that they wanted the Dalai Lama’s excursion to watch the production conducted in absolute secrecy and without any armed Tibetan bodyguards. This seemed a strange request and there was much discussion amongst the Dalai Lama’s advisors. Some members of the Kashag got alarmed and concerned that the Dalai Lama might be abducted, recalling a prophecy that told that the Dalai Lama should not exit his palace.

On 10 March, several thousand Tibetans surrounded the Dalai Lama’s palace to prevent him from leaving or being removed. The huge crowd had gathered in response to a rumour that the Chinese communists were planning to arrest the Dalai Lama when he will go out to attend the cultural performance at the PLA’s headquarters. This marked the beginning of the uprising in Lhasa, though Chinese forces had skirmished with guerrillas outside the city in December of the previous year. At first, the violence was directed at Tibetan officials perceived not to have protected the Dalai Lama or to be pro-Chinese and the attacks on Han Chinese started later.

On 12 March, protesters appeared in the streets of Lhasa declaring Tibet’s independence. Barricades went up on the streets of Lhasa, and Chinese and Tibetan rebel forces began to fortify positions within and around Lhasa in preparation for the conflict. Chinese and Tibetan troops continued moving into position over the next several days, with Chinese artillery pieces being deployed within range of the Dalai Lama’s summer palace, the Norbulingka. On 15 March, preparations for the Dalai Lama’s evacuation from the city were set in motion, with Tibetan troops being employed to secure an escape route from Lhasa. On 17 March, two artillery shells landed near the Dalai Lama’s palace, triggering his flight into exile.

The Dalai Lama crossed the border into India after a 14-day journey on foot from the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, over the Himalayan Mountains. There was no news of his safety or whereabouts since he left Lhasa on 17 March with an entourage of 20 men, including six Cabinet ministers. The Dalai Lama had to cross the 500-yard wide Brahmaputra river and endure the harsh climate and extreme heights of the Himalayas, travelling at night to avoid the Chinese sentry guards. He finally reached the Indian border at the Khenzimana Pass on 29th March, 1959. The Tibetan leader sent two of his officials to contact the Government of India and seek asylum for himself and his party. Asylum was granted to Dalai Lama by the Indian Government. The Dalai Lama was received by the Assam Rifles at Chutangmu in the Tawang sector of Arunachal Pradesh (then NEFA) on March 31, 1959 and became a refugee in India.

As Dalai Lama writes in his autobiography, Freedom in Exile, that, “On arrival, I was greeted by my old liaison officer and interpreter, Mr Menon and Sonam Topgyal Kazi respectively, one of whom handed me a telegram from the Prime Minster: ‘My colleagues and I welcome you and send greetings on your safe arrival in India. We shall be happy to afford the necessary facilities to you, your family and entourage to reside in India. The people of India, who hold you in great veneration, will no doubt accord their traditional respect to your personage. Kind regards to you. Nehru.’”9

On April 3, 1959 Prime Minister Nehru officially confirmed in the Lok Sabha that the Dalai Lama had crossed into Indian territory on March 31st 1959 and announced that political asylum had been granted to the Dalai at the latter’s request. On April 18, the Dalai Lama made his first public appearance on Indian soil at Tezpur and issued a public Statement.

Please see appendix 1 for the full text of Dalai Lama’s statement at Tejpur on 18th April, 1959 and subsequent development on this issue.

(b) The Souring of Sino-Indian Relations and the Border Dispute During 1959

In his 14 December 1958 letter – the first letter he sent on the Sino-Indian border dispute – Nehru pressed the Chinese regarding maps printed there stating that, “…he was ‘puzzled’ by the Chinese desire (expressed in Peiping’s note of 3 November 1958) to conduct surveys to find a ‘new way of drawing the boundary of China,’ because ‘I had thought that there was no major boundary dispute between China and India.’ Nehru was telling Chou by implication that the Chinese premier was breaking a tacit – or gentlemen’s – agreement regarding the border.”10

“In his January 1959 letter of reply, Chou conceded that the border issue was not raised in his talks with Nehru in 1954, but gave as the reason for this the view that ‘conditions were no yet ripe for its settlement’ – a hint that Chou in 1954 had been trying to avoid injecting a contentious issue into the young and cordial Sino-Indian friendship. He reminded Nehru that ‘questions’ had been kept in ‘diplomatic channels,’ and implied that he preferred this practice to continue.

Chou then made a significant reversal of the entire Chinese position on the border issue. Chou (1) implied that the old maps were accurate at most points, (2) stated that there would be ‘difficulties’ in changing them, and (3) alluded to the Chinese people’s objection to Indian maps claiming the western sector.”11

Chou wanted Nehru to maintain the status-quo until the entire boundary was surveyed and formally delimited and stated, “Our government would like to propose to the Indian Government that, as a provisional measure, the two sides temporarily maintain the status quo, that is to say, each side keep for the time being the border areas at present under its jurisdiction and not go beyond them.

This position meant that the Chinese would continue to occupy the Aksai Plain. The Chinese leaders probably anticipated a sharp reaction from Nehru and his advisers and perhaps even more active Indian patrolling into Chinese-controlled territory. Nehru’s reply, expressing shock at the Chinese definitive position, was delivered in a letter to Chou (22 March 1959) after the outbreak of the Tibetan revolt.”12

In his March 22, 1959 reply to Chou En-Lai’s January 1959 letter, Nehru flatly asserted, “A treaty of 1842 between Kashmir on the one hand and the Emperor of China and the Lama Guru of Lhasa on the other mentions the India-China boundary in the Ladakh region. In 1847, the Chinese government admitted that this boundary was sufficiently and distinctly fixed. The area now claimed by China has always been depicted as part of India on official maps, has been surveyed by Indian officials and even a Chinese map of 1893 shows it as Indian territory.”13

As we have seen in our detailed account of Sino-Indian Relations above, the claims of Nehru were, simply, not correct. According to A.G. Noorani, “The treaty of 1842 did not define that border at all. It was a non-aggression pact concluded after the end of hostilities. It simply affirmed the boundaries that existed ‘formerly’. The linear boundary came with the British. India, like others, had frontier zones. If, indeed, the boundaries were defined in 1842, why did the British pursue China for a definition of the boundaries soon after Kashmir came under British suzerainty under the Treaty of Amritsar on March 9, 1846? China, weak and insecure, rebuffed the overtures saying, on January 26, 1847, that since its territory ‘has its ancient frontier, it was needless to establish any other’. This is what Nehru cited as acceptance of his claim to a defined border.

If the boundary in Ladakh was defined, where was the need for: (1) The protracted Sino-British correspondence on the subject from 1846-1848, 16 letters in all; (2) Two unsuccessful Boundary Commissions in 1846 and 1847; and (3) Britain’s Note to China on March 14, 1899, proposing a definite boundary for northern and eastern Kashmir.

There are, besides, many internal British memoranda on the need for a definite boundary. Two questions cannot be evaded: (1) Was Nehru ignorant of this none too voluminous record? and (2) Did Gopal not draw his attention to them? Nehru’s assertion that Aksai Chin was always depicted as part of India’s territory was untrue to his own knowledge. He had himself revised the maps in 1954, after all. Remember, his reply was written after due deliberation, two whole months after Zhou’s letter, no doubt with Gopal’s assistance.

Sarvepalli Gopal (1923-2002) was a well-known Indian historian. He was a Director in the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, and worked closely with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in the 1950s. Dr. S. Gopal, participated in the border expert’s talks between India and China in 1960 and before the meeting he was sent to London to try to strengthen the documentation of India’s claims over the Aksai Chin area.

On each of the three factors, Nehru went wrong. The territory in the crucial sector in Ladakh was of no strategic value and was not part of India’s territory either. It was never ‘surveyed’ by India, as he claimed. It was of strategic importance to China since the Xinjiang-Tibet road ran through it. Likewise, the McMahon Line was of strategic importance to India. This is the one boundary dispute that should have been the easiest to resolve because each side had its own vital non-negotiable interest exclusively within its own control. This was a pre-eminently negotiable dispute.”14

(1) The Longju Incident

“The failure of the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the 14th Dalai Lama’s arrival in India in March led Indian parliamentarians to censure Nehru for not securing a commitment from China to respect the McMahon Line. Additionally, the Indian press started openly advocating Tibetan independence. Nehru, seeking to quickly assert sovereignty in response, established ‘as many military posts along the frontier as possible’, unannounced and against the advice of his staff. On discovering the posts, and already suspicious from the ruminations of the Indian press, Chinese leaders began to suspect that Nehru had designs on the region.”15

“Longju was and is just north of the McMahon Line according the inside back cover map in Maxwell and according to notable Indian mountaineer Harish Kapadia who explored the area in 2005. His published map and text locate Longju a kilometre or two on the China side of the McMahon Line ‘near the Chinese garrison town of Migyitun’”16

“On 25 August, a Chinese troop detachment exchanged fire with a 12-man Indian picket in the area south of Migyitun, (Map 2) capturing four and on 26 August, a Chinese force outflanked Longju, (Map 2) opened fire, and forced Indian troops to abandon the post. New Delhi’s protest of 28 August characterized these Chinese actions as ‘deliberate aggression,’ pointed out that ‘until now’ New Delhi had observed a ‘discreet reticence’ about them, but they constitute a matter ‘which is bound to rouse popular feelings in India.’ The last remark indicated that Nehru saw the August actions as the last straw and envisaged a public outburst. Until the very latest incident – the 25-26 August firefight – Nehru had maintained a position as unprovocative to the Chinese as possible. For example, on 20 August he told Ambassador Bunker that India’s UN delegation would not condemn China for action in Tibet and would continue to sponsor Peiping’s case for UN representation. On 25 August he told Parliament that he did not ‘think’ any Chinese soldier had crossed into Indian territory in pursuit of Tibetans – giving Peiping the benefit of the doubt despite many reports of Chinese border crossings to capture rebels. However, the 25-26 August skirmish could not be played down and could hardly be tossed off as a minor harassment unworthy of public indignation or serious official concern. To do so would have been an unpardonable display of official callousness and of political ineptitude.

Nehru’s first sally in his speech to a tense and excited Parliament on 28 August was to caution against being ‘alarmist’ and indulging in shouting and strong talk. Parliament members, however, were not subdued as they expressed their anxiety over the incidents and Chinese intentions along the entire border. A senior member of the Congress Party asked whether bombs could be dropped to chase the Chinese out of the NEFA. Another asked: if India failed to defend its own territory, what would be the fate of small Asian countries which look to India for guidance? Nehru was calm: he reaffirmed the Indian position that any aggression against Bhutan and Sikkim will be considered aggression against India, detailed a number of earlier border incidents, and in response to a suggestion, indicated willingness to issue a ‘White Paper’ on Chinese border violations. Nehru in this way succeeded in keeping down violent condemnations of Peiping, but the explosive temper of Parliament and the press spread and pervaded non-official thinking. Nehru found himself under heavy pressure to make good on the government’s pledge to resist Chinese intrusions along the Tibetan frontier.

Why did the Chinese outrage Indian opinion and, more importantly, undercut Nehru, who had concealed earlier patrol encounters, by firing on Indian troops south of Migyitun and at Longju? Even if we assume that the 25-26 August skirmishes were provoked by the Chinese, they seem to have stemmed largely from an increased Indian presence along the eastern sector of the border, along which the Indians had 8 checkposts. As noted earlier in this paper, the Chinese also suspected the Indians (and others) of providing some support to Tibetan rebels using Indian soil as a sanctuary, and on 23 June had delivered a strong protest over the forceful Indian ‘occupation’ of the Migyitun area and aid given to the rebels from the post. Following the revolt, Indian personnel had moved up into some posts – the Chinese claimed they moved into 10 – including several on Chinese territory. Inasmuch as the Indians conceded that Migyitun is on the Chinese-side of the McMahon Line, it seems probable that the Chinese felt on firm political ground in starting the action to sweep the area ‘south of Migyitun’ including Longju free of Tibetans.”17

The McMahon Line, “For a good deal of its length it follows an unmistakable and inaccessible crest-line, but elsewhere it is drawn over indeterminate topographical features and there the only way to determine the line of the boundary is to trace it out on the ground from the coordinates of McMahon’s original map. Often that process would create an inconvenient or nonsensical boundary, and since the line marked thickly on the original, eight-miles-to-the-inch map covers about a quarter of a mile, even this could produce no precise delineation on the ground. But, short of a joint Sino-Indian demarcation process, there is no way to fix the McMahon Line on the ground.

One of the places in which McMahon made his line diverge from what his map showed as the highest ridge was near a village called Migyitun, on a pilgrimage route of importance to the Tibetans. In order to leave Migyitun in Tibet, the line cut a corner and for about twenty miles, until it met the main ridge again, followed no feature at all. As the Indians reconnoitred the area in 1959, they discovered that the topography made a boundary alignment immediately south of Migyitun, rather than about two miles south as shown on the map, more practical from their point of view, and they set up a border post accordingly. The reasons for the Indian adjustment of the line here have not been stated clearly, but it seems probable that it was decided that a river, the Tsari, running roughly west-east just south of Migyitun, should be the boundary feature. Advancing the boundary to the river put a hamlet called Longju, on the opposite side of the valley from Migyitun, within India, while providing a more practical site for Indian border post.

The reasoning was unexceptionable; minor variation from a map line are almost invariably found necessary in boundary demarcation. But demarcation must be a joint process, and the Indians on this occasion were acting unilaterally, establishing their border posts on what their own maps showed as Chinese territory without seeking China’s approval, or even intimating their intention. Later the Indians made no secret of their action. In September 1959 Nehru told the Lok Sabha that, while by and large the McMahon Line was fixed, ‘in some parts, in the Subansiri area (Migyitun adjoins the Subansiri division of the NEFA, Map 2) or somewhere there, it was not considered a good line and it was varied afterwards by us, by the Government of India.’ In a letter to Chou En-lai in the same month Nehru rejected the Chinese complaint that Indians were overstepping the McMahon Line. But in the same breath he admitted that the Indian claim in the Migyitun area ‘differs slightly from the boundary shown in the treaty map.’ He justified this with the explanation that the Indian modification ‘merely gave effect to the treaty map in the area, based on definitive topography’, and argued that it was in accordance with established international principles. So it would have been, if done in consultation with China.”18

“As India could not – and Nehru was disinclined to – restrain the Chinese by launching attacks at border posts, Nehru tried to restrain them politically. He moved in two directions: (1) he informed the Russians of his predicament with the Chinese and (2) appealed to any desire in Peiping for negotiating ‘small’ border issues.”19

Russians were briefed on the Longju incident by India. “Soviet leader Khrushchev discussed this incident with Mao and Zhou during his early October 1959 visit to Beijing. Khrushchev was dismayed with the spiralling tension in Sino-Indian relations and wanted an explanation of the 25 August incident. Both Zhou Enlai and Mao assured Khrushchev that the Chinese handling of that incident had been at the initiative of the local commander and without central authorization. ‘We did not know until recently about the border incident, and local authorities undertook all the measures there without authorization from the centre,’ Zhou told Khrushchev. ‘The rebuff was delivered on the decision of local military organs,’ Mao said. Mao and Zhou assured the Soviet leader that China desired peaceful resolution of the border problem and avoidance of conflict with India.

In September, just before Khrushchev’s visit, Chinese leaders had met in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, to consider how to avoid further bloodshed on the border with India. Mao, Zhou, PRC President Liu Shaoqi, Beijing mayor and Politburo member Peng Zhen, Mao’s secretary Hu Qiaomu, and General Lei Yingfu participated. The meeting began with a report by Lei on the border situation. Lei recounted repeated calls from front line commanders for ‘rebuff’ (huanji) of India’s “blatant aggression” against China. Mao became somewhat exasperated at this and observed that conflict was inevitable as long as soldiers of the two sides were ‘nose to nose’. He, therefore, proposed a withdrawal of 20 kilometres. If India was unwilling to do this, Mao suggested, China would unilaterally withdraw. ‘Meeting participants unanimously supported Chairman Mao’s suggestion,’ according to Lei Yingfu. Thus, Chinese forces were ordered to withdraw 20 kilometres from what China felt was the line of actual control, and to cease patrolling in that forward zone. Further Chinese measures to decrease tension on the border were adopted in January 1960 (prohibiting target practice, food gathering, exercising, etc, within the forward zone). Tension declined for 23 months. It began to spiral again in November 1961 when India started implementing its Forward Policy.”20

Nehru conveyed his appeal to the Chinese for border negotiations through his statements in Indian Parliament on 31 August and 4 September, 1959. “On 31 August he rejected suggestions for strong action against the Chinese on the ground that a ‘big country could not behave as though at war and hit out all around,’ was more conciliatory than on 20 August, and emphasized India’s desire for settlement through discussion of ‘small border disputes’ of about ‘a mile or two’ of territory. He told one questioner that India would not try to reoccupy the Aksai Plain by force or bomb the Sinkiang-Tibet road, but would send another request that New Delhi’s 8 November 1958 protest note be answered. India, he continued would seek a settlement through talks. Nehru stated that the Chinese-held Aksai Plain was all ‘barren land.’ This line – i.e., that this corner of Ladakh was after all just wasteland and not worth fighting for – was to be repeated publicly and privately, partly to minimize the importance of its loss and partly to prepare Indian opinion for eventual negotiations regarding ownership.”21

By early September, Nehru was feeling deeply hurt because he had not had any response from Chou of the dozen or more personal letters that he had written to him since his March 1959 letter. On 7th September Nehru submitted to the Parliament a “White Paper” on the Sino-Indian exchanges of recent years. On 8th September Chou sent a personal, long-delayed letter, replying to Nehru’s March letter. “Chou began professing surprise that there was a ‘fundamental difference’ on the border issue (but not denying it), repeated his January 1959 suggestion to maintain status quo, and called for step by step preparations for an ‘over-all settlement’ on the basis of this status quo. He then presented a definitive, ‘further explanation’ of the Chinese position, the basic premise being that the border ‘has never been formally delimited.’

The gist of this position, as Chou presented it, is as follows: (1) Peiping does not recognize the McMahon Line in the eastern sector. It has been secretly formalized by British and Tibetan representatives and surreptitiously attached to the Simla Treaty of 1914, which was never ratified by a Chinese government. Nevertheless, for the sake of amity along the border and ‘to facilitate’ negotiations and settlement of the border issue, ‘Chinese troops have never crossed that line.’ (2) The border in the middle sector – i.e., the Tibet-Uttar Pradesh border – has never been delimited (‘you also agree’ that this is so). (3) In the western sector – i.e. the Ladakh border with Sinkiang and Tibet – Peiping recognizes the ‘traditional customary line’ as the boundary. This ‘traditional customary line’ has been ‘derived from historical traditions’ and ‘Chinese maps have always drawn the boundary’ in accordance with this line. (4) China’s border with Sikkim and Bhutan is a question beyond the scope of the immediate Sino-Indian issue and China has always respected the ‘proper’ relations between them and India. Chou’s statement that Chinese troops had never crossed the McMahon Line because Peiping desired ‘to facilitate’ negotiations and a settlement constituted an official hint that Peiping would be willing to exchange its map claim to the NEFA for Indian agreement to Chinese possession of the Aksai Plain in Ladakh. This hint of a swap was repeated in an NCNA (New China News Agency) release of ‘Data on the Sino-India Border Question’ of 10 September and was given added point by the claim that Indian maps on the western sector extended Indian territory ’38,000 square kilometres deep into Chinese territory.’

The remaining portion of the letter was an attempt to reverse Indian charges of Chinese military initiatives in August. Armed attacks launched by Indian troops on Chinese ‘frontier guards’ at Migyitun had left these ‘frontier guards no room but to fire in self-defence.’ ‘This was the first instance of armed clash along the Sino-Indian border.’ Chinese ‘guard units’ had been despatched to the border ‘merely for the purpose of preventing remnant armed Tibetan rebels from crossing the border back and forth.’ Chou concluded by urging Nehru to withdraw ‘trespassing’ Indian troops and restore ‘Long-existing state of the boundary’ in order to ease the ‘temporary tension’ between India and China.”22

(2) Nehru’s Letter of 26th September, 1959

After the receipt of Chou’s letter Nehru was shocked and deeply disillusioned with him. In response he wrote a very long letter to Chou on the 26th of September which began thus: “I have received your letter of September 8, 1959. I must say that I was greatly surprised and distressed to read it. You and I discussed the India- China border, and particularly the eastern sector, in 1954 in Peking and in 1956-57 in India. As you know; the boundary in the eastern sector is loosely referred to as the McMahon Line. I do not like this description, but for convenience I propose to refer to it as such. When I discussed this with you, I thought that we were confronted with the problem of reaching an agreement on where exactly the so-called McMahon Line in the eastern sector of the boundary lay. Even when I received your letter of January 23, 1959, I had no idea that the People’s Republic of China would lay claim to about 40,000 square miles of what in our view has been indisputably Indian Territory for decades and in some sectors for over a century. In your latest letter you have sought to make out a claim to large tracts of Indian territory and have even suggested that the independent Government of India are seeking to reap a benefit from the British aggression against China. Our Parliament and our people deeply resent this allegation. The struggle of the Indian people against any form of imperialism both at home and abroad is known and recognised all over the world and we had thought that China also appreciated and recognised our struggle. It is true that the British occupied and ruled the Indian sub-continent against the wishes of the Indian people. The boundaries of India were, however, settled for centuries by history, geography, custom and tradition. Nowhere indeed has India’s dislike of imperialist policies been more clearly shown than in her attitude towards Tibet. The Government of India voluntarily renounced all the extra-territorial rights enjoyed by Britain in Tibet before 1947 and recognised by Treaty that Tibet is a region of China. In the course of the long talks that we had during your last visit to India, you had told me that Tibet had been and was a part of China but that it was an autonomous region.”23

This letter point by point answers Chou’s letter and provided detailed arguments in support of his earlier commentaries that on most of the stretches of the long Sino-Indian border a well-defined border has historically existed for a long time between the past two centuries. He concluded his letter by reminding Chou of the record of India’s friendliness to China and adding, ‘I appreciate your statement that China looks upon her south-western border as a border of peace and friendship. This hope is promise could be fulfilled only if China would not bring within the scope of what should essentially’ be a border dispute, claims to thousands of square miles of territory which have been and are integral part of the territory of India.”24

(3) The October 21, 1959 Kongka Pass (Ladakh) Clash

On October 21, Chinese military clashed with an Indian border police patrol party at Kongka Pass (Map 1) in southern Ladakh, capturing 10 and killing 9 Indian Policemen. “According to the Chinese version (23 October NCNA release), Chinese ‘frontier guards’ on 21 October had been ‘compelled’ to fire in self-defence on Indian ‘armed personnel more than 70 in number, ‘after disarming three Indians on 20 October.’ According to the Indian version (24 October statement of the External Affairs Ministry), Chinese troops entrenched on a hill-top position opened sudden and heavy fire, using grenades and mortar, on the border police party searching for two constables and porter, who had failed to return from patrol on 20 October. Although the Indian police fired back, they were ‘overwhelmed’ by Chinese strength in number and arms.”25

“When Nehru discussed the clash at a public meeting on 25 October, he seemed to be aware of the military handicaps under which India operated along the border in Ladakh. His approach was to temporize and warn against the ‘brave talk’ of Indians who called for a counterattack on the Chinese. But Parliament and the press insisted on some form of Indian military action: the Hindustan Times called for limited reprisals in order to avoid demoralizing Indians and permit the feeling of helplessness to continue, and the Indian Express stated that New Delhi should now accept aid from non-Communist countries ‘without qualms.’ Nehru rejected any idea of India’s abandoning its non-alignment policy at a 1 November public meeting, claiming that military aid from abroad would jeopardize India’s freedom and shatter India’s place in the world. India, he continued, was the one country in Asia which did not join alliances but which walked ‘with its head held high not bowing to anyone.’ He could not give an assurance that the Chinese would not cross the border, but India would defend the border ‘with all her might.’ Nehru declined to comment on the strategic measures being taken to deal with the border situation, but sought to explain why the Ladakh border was not protected by forces in larger numbers; ‘we thought that the Chinese would not resort to force in Ladakh area.’ In addition, if India has placed a ‘large army’ in Ladakh, it might have been cut off and could not have been shifted easily in the event of an emergency elsewhere on the border.”26

“The alternative courses of military action apparently considered by the Indians in late October 1959 were (1) to prepare to initiate action to recapture India-claimed territory in Ladakh held by the Chinese or (2) to concentrate on preventing penetration of the rest of the border while accepting the Chinese presence in Ladakh, virtually writing it off. They apparently decided on (2).

Nehru was responsible for the decision, and began to prepare Indian public opinion for the cession of Chinese-occupied sections of Ladakh. The procedure used was simply to reassert the line that most of Ladakh was wasteland. Nehru is reliably reported to have stated in late October sessions of the External Affairs subcommittee that he was willing to begin open negotiations on the determination of the Ladakh border. He emphasized that the disputed area of Ladakh is of ‘very little importance – uninhabitable, rocky, not a blade of grass’ – and went on to imply that he would not be averse to the ultimate cession of that part of eastern Ladakh claimed by the Chinese. In conversations at the time with army and government officials, members of the American embassy staff were told that the Aksai Plain is not regarded as strategically important or useful to India. The Indians stated repeatedly that it is a ‘barren place where not a blade of grass grows.’ Both, Foreign Secretary Dutt and Vice President Radhakrishnan, complained bitterly that Nehru was on the way to selling out the Aksai Plain.

The developing line about the strategic insignificance of the Aksai Plain was strengthened by the Indian military estimate that the Plain was indefensible anyway. General Thimayya’s statement was that the ridge line of Karakoram Range is the only defensible frontier in the entire Ladakh area. Thimayya stated that therefore part of the Tibetan Plateau east of the ridge line shown as Indian territory on New Delhi’s maps was ‘militarily indefensible,’ and by implication there was really no strategic reason for recapturing it from Chinese troops even if it were possible to do so in the face of ‘preponderant Chinese military power.’ This view provided Nehru with another rationalization for his talk rather than fight decision. He also stated privately that the entire border in Ladakh is undefined, that few Indians live in the area, that there was never been any real administration there, and that therefore he is not sure that all the territory claimed in Ladakh belongs to India.

However, Indian officials were well ahead of Nehru in the desire to take a harder line with the Chinese. When, on 29 October, Nehru was informed by telegram that the Chinese had told the Indian ambassador that their troops were merely occupying Chinese territory and there could be no question of withdrawals prior to negotiations, Nehru drafted a reply which President Prasad disliked on the grounds that it ‘lacked firmness.’ Only after this objection did Nehru strengthen the language in his note of 4 November.

In this note, New Delhi avoided the line which Nehru had been developing regarding the strategic insignificance of the Aksai Plain. The Aksai Plan was specifically declared to be Indian territory. Peiping was warned that incursions south of the McMahon Line would be considered ‘a deliberate violation’ of Indian territory. The August and October clashes were said to be ‘reminiscent of the activities of the old imperial powers,’ and an annexed report gave the view of the senior surviving Indian police officer to the effect that October clash was initiated by the Chinese, who fired first ‘using heavy weapons.’ Despite the note’s implication that only ‘minor frontier disputes’ were negotiable, it did not make Peiping’s recognition of Indian claims to the Aksai Plain a pre-requisite for talks.

Had it not been Nehru, but rather a more military-minded man who occupied the post of Prime Minister in late October 1959, a priority program to prepare India eventually to fight would have been started. In the course of two months, India had been humiliated by two military defeats and the public and government officials had been aroused to anger against the nation’s enemy as never before in its short history. But Nehru insisted that war with China was out of the question, and apparently did not think the challenge justified the economic burden of increased military spending. A man of different temperament and background, no less aware of the hard facts of Indian military inferiority, might nevertheless have felt that the country must be mobilized to prepare for long-due military revenge against the Chinese at all costs. Guts and action, not words, was the military man’s attitude in late October. This was not Nehru’s way, however, and his authority and prestige in the country (although questioned more extensively than ever before) were still sufficiently great to reject preparedness for an eventual recourse to arms.

At an emergency cabinet meeting in late October, Nehru indicated that border fighting did not constitute a threat to India. The strategic Chinese threat, he maintained, lies in the rapidly increasing industrial power base of China as well as the building of military bases in Tibet. The only Indian answer, he continued, is the most rapid possible development of the Indian economy to provide a national power base capable of resisting a possible eventual Chinese Communist military move. Nehru seemed to believe that the Chinese could not sustain any major drive across the ‘great land barrier’ and that the Chinese threat was only a long-term one.

Nehru’s statements along the line that the Chinese military threat was not immediate but long-range may have reflected the strategic assessment made by his military leaders. The problem of logistics was so enormous, in their view, that the Chinese would find it ‘impossible’ to initiate and sustain a major offensive into and through Ladakh and the NEFA. Thimayya’s estimate was that the Karakoram Range (Map 1) crest-line in the west and the crests of the Himalayan main range in the east provide effective land barriers against a major Chinese military push. Thimayya held the view in late October that any Chinese venture in force into the Ladakh area would be reckless ‘in view of Chinese supply and transport problems’ and that the defensive capabilities of even limited Indian armed forces in this terrain would be formidable.

To what extent these views reflected a mere rationale for New Delhi’s failure to strike back at Chinese forces on the border is conjectural. Certainly Nehru’s idea of first building a national economic base is a platitude in the context of the border dispute. The idea that the Chinese would face insurmountable logistics problems in the event of a major drive south, however, seemed to be firmly fixed in Indian military thinking. On balance, Indian estimates of Chinese capabilities and intentions along the border supported Nehru’s policy of no-war and a negotiated settlement.”27

“The Chinese leaders recognized, or were made aware, shortly after the August 1959 clashes, that Nehru’s advisers might use these skirmishes to push him and the entire government further to the ‘right’ – i.e. towards a militant anti-China policy and a willingness to accept some degree of American support in this policy. The practical strategic danger such a development posed was that the arc of U.S. bases ‘encircling’ China would be extended through India. Both Mao Tse-tung and Liu Shao-chi reportedly alluded to the danger in their talks with Indian party boss Ajoy Ghosh in Peiping in early October 1959.”28

“This persistent concern with ‘encirclement’ by military regimes combined with General Thimayya’s attempt to force Krishna Menon’s removal as defence minister apparently raised real fears among the Chinese leaders (as it had among the Indian Communists) that India was on the brink and ‘must be snatched away from going into the U.S. imperialist camp.’

…Regarding their appraisal of Nehru’s political attitude, Mao is reported to have told Ghosh on 5 October that the Chinese recognize – as Ghosh did – a difference between Nehru and certain of his advisers. The latter, particularly those in the Ministry of External Affairs and including General Thimayya, were ‘rightists’ who wanted to exploit the border dispute to help the U.S. ‘isolate China.’ According to Liu Shao-Chi’s remarks to Ghosh on 8 October, Nehru might decide in favour of these ‘rightists,’ but for the present all efforts should be directed toward preventing him from doing so.”29

All these factors contributed to the Chinese desire to settle the entire border dispute through Sino-Indian negotiations. In his letter of November 7, 1959 Chou proposed that, “…the border disputes which have already arisen should be settled amicably and peacefully, and that pending a settlement the status quo should be maintained and neither side should seek to alter the status quo by any means. In order to maintain effectively the status quo of the border between the two countries, to ensure the tranquillity of the border regions and to create a favourable atmosphere for a friendly settlement of the boundary question, the Chinese Government proposes that the armed forces of China and India each withdraw 20 kilometres at once from the so-called McMahon line in the east, and from the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west, and that the two sides undertake to refrain from again sending their armed personnel to be stationed in and patrol the zones from which they have evacuated their armed forces, but still maintain civil administrative personnel and unarmed police there for the performance of administrative duties and maintenance of order. This proposal is in effect an extension of the Indian Government’s proposal contained in its note dated September 10 that neither side should send its armed personnel to Longju, to the entire border between China and India…”30

He went on to add that, “the Chinese Government is willing to do its utmost to create the most peaceful and most secure border zones between our two countries, so that our two countries will never again have apprehension or come to a clash on account of border issues… The Chinese Government has never had the intention of straining the border situation and the relations between the two countries. I believe that Your Excellency also wishes to see the present tension eased. I earnestly hope that, for the sake of the great, long-standing friendship of the more than 1,000 million people of our two countries, the Chinese and Indian Governments will make joint efforts and reach a speedy agreement on the above-said proposal.

The Chinese Government proposes that in order to discuss further the boundary question and other questions in the relations between the two countries, the Prime Ministers of the two countries hold talks in the immediate future.”31

The Indian leaders did not accept Chou’s proposals and advanced their own as follows:

- Chinese withdraw from Longju, with India ensuring that it will not be reoccupied by Indian forces.

- Mutual Indian and Chinese withdrawal from the entire disputed area in Ladakh. Indian troops would withdraw south and west to the Chinese 1956 claim line (Map 1) shown in Chinese maps and Chinese troops would withdraw north and east to the line claimed by India on its maps

- Personal talks with the Chinese Prime Minister are acceptable, but only after preliminary steps are taken to reach an “interim understanding” to ease tensions quickly.

- A mutual 20 kilometres withdrawal all along the border is unnecessary, as no clashes would occur if both sides refrained from sending out patrols, India having already done this.

Nehru’s letter to Chou was dispatched on the 16th November. Chou’s 17th December letter in response to it is extremely important on the whole issue of Sino-Indian border dispute.

After welcoming Indian proposal for the frontier outposts of the two sides to stop sending out patrols he said, “But the Chinese Government would like to ask for clarification on one point, that is: The proposal to stop patrolling should apply to the entire Sino-Indian border, and no different measure should be adopted in the sector of the border between China and India’s Ladakh.

The Chinese Government is very much perplexed by the fact that Your Excellency put forward a separate proposal for the prevention of clashes in the sector of the border between China and India’s Ladakh. The Chinese Government deems it necessary to point out the following: (1) There is no reason to treat this sector of the border as a special case. The line up to which each side exercises actual control in this sector is very clear, just as it is in the other sectors of the Sino-Indian border. As a matter of fact, the Chinese map published in 1956, to which Your Excellency referred correctly shows the traditional boundary between the two countries in this sector. Except for the Parigas area (Map 1) by the Shimgatsangpu River, India has not occupied any Chinese territory east of this section of the traditional boundary. (2) This proposal of Your Excellency’s represents a big step backward from the principle agreed upon earlier by the two countries to maintaining for the time being the state actually existing on the border. To demand a great change in this state as a pre-condition for the elimination of border clashes is not to diminish but to widen the dispute. (3) Your Excellency’s proposal is unfair. Your Excellency proposes that in this sector Chinese personnel withdraw to the east of the boundary as shown on Indian maps and Indian personnel withdraw to the west of the boundary as shown on Chinese maps. This proposal may appear ‘equitable’ to those who are ignorant about the truth. But even the most anti-Chinese part of the Indian press pointed out immediately that, under this proposal, India’s ‘concession’ would only be theoretical, because, to begin with, the area concerned does not belong to India and India has no personnel there to withdraw, while China would have to withdraw from a territory of above 33,000 square kilometres, which has long belonged to it, its military personnel guarding the frontiers and its civil administrative personnel of the Hotien County, the Sinkiang Uighur Autonomous Region, and of Rudok Dzong in the Ari area of the Tibet Autonomous Region respectively. (4) This area has long been under Chinese jurisdiction and is of great importance to China. Since the Ching Dynasty, this area has been the traffic artery linking up the vast regions of Sinkiang and western Tibet. As far back as in the latter half of 1950 it was along the traditional route in this area that units of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army entered the Ari area of Tibet from Sinkiang to guard the frontiers. In the nine years since then, they have been making regular and busy use of this route to bring supplies. On the basis of this route, the motor-road over 1,200 kilometres long from Yehcheng in south-western Sinkiang to Gartok in south western Tibet was built by Chinese frontier guard units together with more than 3,000 civilian builders working under extremely difficult natural conditions from March 1956 to October 1957, cutting across high mountains, throwing bridges and building culverts. For up to 8 or 9 years since the peaceful liberation of Sinkiang and Tibet when units of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army began to be stationed in and patrol this area till September 1958 when the intrusion of the area by armed Indian personnel occurred, so many activities were carried out by the Chinese side in this area under its jurisdiction and yet the Indian side was utterly unaware of them. This is eloquent proof that this area has indeed always been under Chinese jurisdiction and not under Indian jurisdiction. Now the Indian Government asserts that this area has all along been under Indian jurisdiction. This is absolutely unconvincing.

If the Indian Government, after being acquainted with the above view points of the Chinese Government, should still insist that its demand in regard to this area is proper, then the Chinese Government would like to know whether the Indian Government is prepared to apply the same principle equally to the eastern sector of the border, that is to say, to require both the Chinese and Indian sides to withdraw all their personnel from the area between the so-called McMahon line and the eastern section of the Sino-Indian boundary as shown on Chinese maps (and on Indian maps too during a long period of time). The Chinese Government has not up to now made any demand in regard to the area south of the so-called McMahon line as a pre-condition or interim measure, and what I find difficult to understand is why the Indian Government should demand that the Chinese side withdraw one-sidedly from its western frontier area.

Your Excellency and the Indian Government have repeatedly referred to the historical data concerning the Sino-Indian boundary as produced by the Indian side. The Chinese side had meant to give its detailed reply to Your Excellency’s letter of September 26 and the note of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs of November 4 in the forthcoming talks between the Prime Ministers of the two countries, and thought it more appropriate to do so. Since the talks between the two Prime Ministers have not yet taken place, however, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs will give a reply in the near future.”32

One cannot reasonably deny the Chinese Government’s right to demand that we apply the same standards in both Eastern and Western Sectors. If India was prepared to withdraw from the area according to the Chinese claim line of 1956, in the Western Sector, why not in the Eastern Sector (NEFA) where Chinese claims were of a far greater magnitude – an area of almost 90,000 square kilometres as opposed to only about 30-35,000 in the Western Sector (Ladakh). This was a golden opportunity for India to settle our border with China for good. All the unpleasant happenings and disasters of the early 1960s and the incalculable huge psychological cost of the 1962 national humiliation would have been avoided. We would have been on a very different and much more elevated course in our relations with our other neighbours if we had managed truly warm and friendly relations with our biggest neighbour. In his December 21 reply to Chou’s letter Nehru did not respond to Chou’s questioning of Indian Government’s double standards in dealing with Eastern and Western Sectors. He regretted that his ‘very reasonable proposals’ had not been accepted and the unfriendly and very harsh way in which Indian personnel captured in the Chang Chenmo Valley had been treated. Nehru also turned down Chou’s suggestion for a meeting between the two on December 26.

“Nehru’s uncompromising official position had been reached in large part as a result of cabinet, Opposition, and public pressure and it apparently was difficult for him to abandon this stand and simultaneously satisfy public opinion. He nevertheless ruled out military action and left the door open for future negotiations. When chided by an opponent in Parliament on 21 December regarding the desirability of any negotiations with the Chinese, Nehru angrily replied that there were only two choice, ‘war or negotiation.’ ‘I will always negotiate, negotiate, negotiate, right to the bitter end.’ On 22 December, he expressed surprise in Parliament at the idea of ‘police action,’ which, he insisted, is possible only against a very weak adversary. ‘Little wars,’ Nehru continued, do not take place between two great countries and any kind of warlike development would mean ‘indefinite’ war because neither India nor China would ever give in and neither could conquer the other.”33

As promised by Chou in his 11th December letter, a Note containing a very detailed and well reasoned reply to Nehru’s 26th September letter was delivered by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China to the Embassy of India in China on 26th December 1959. This Chinese Note was moderate in tone. At the outset it declared: “China and India are two peace-loving, big countries with a long history of mutual friendship and with many great common tasks both at present and in the future. Friendship between China and India is in the interests not only of the two peoples, but also of world peace, particularly of peace of Asia. The Chinese Government is therefore very reluctant to engage in argument with the Indian Government over the boundary question. Unfortunately, the Sino-Indian boundary has never been delimited. Britain left behind in this respect a heritage of certain disputes and moreover the Indian Government has made a series of unacceptable charges against China, thereby rendering these arguments unavoidable. Because the Indian Government has put forth a mass of detailed data on the boundary question, the Chinese Government feels sorry that, though trying its best to be brief, it cannot but refer in this reply to various details so as to clarify the true picture of the historical situation and the views of the two sides.”34

The long Note was concluded by asking, “What are the key questions which demand an urgent solution right now? The Chinese Government has the honour to present the following opinions to the Indian Government:

(a) The Chinese Government is of the opinion that no matter what views the two sides may hold about any specific matter concerning the boundary, there should no longer be any difference of opinion about the most basic fact known to the whole world, that is the entire boundary between the two countries has indeed never been delimited, and is therefore yet to be settled through negotiations. Recognition of this simple fact should not create any difficulties for either side, because it would neither impair the present interests of either side, nor in any way prevent both sides from making their own claims at the boundary negotiations. Once agreement is reached on this point, it could be said that the way has been opened to the settlement of the boundary question. Although up to now each side has persisted in its own views on the concrete disputes concerning the different sectors of the boundary, provided both sides attach importance to the fundamental interest of friendship of the two countries and adopt an unprejudiced attitude and one of mutual understanding and accommodation, it would not be difficult to settle these disputes. If India’s opinions prove to be more reasonable and more in the interest of friendship of the two countries, they should be accepted by China; if China’s opinions prove to be more reasonable and more in the interest of friendship of the two countries, they should be accepted by India. It is the hope of the Chinese Government that the forthcoming meeting between the Prime Ministers of the two countries will first of all reach agreement on some principles on the boundary question so as to provide guidance and basis for the future discussion and the working out of a solution by the two sides.

(b) Pending the formal delimitation of the boundary, the status quo of the border between the two countries must be effectively maintained and the tranquillity of the border ensured. For this purpose, the Chinese Government proposes that the armed forces of the two sides along the border respectively withdraw 20 kilometres or some other distance considered appropriate by the two sides, and that, as a step preliminary to this basic measure, the armed personnel of both sides stop patrolling along the entire border.

The Chinese Government believes that if agreement can be reached on the two points mentioned above, the situation on the Sino-Indian border will undergo an immediate change and the dark clouds hanging over the relations between the two countries will quickly vanish. The Chinese Government earnestly hopes that the views it has set forth here at great length on the past, present, and future of the Sino-Indian boundary question would receive the most good-willed understanding of the Indian Government, thereby helping to bring about a settlement of this question satisfactory to both the sides and a turn for the better in the relations between the two countries. Although some arguing cannot be helped in order to make reply to unfair charges, the intention and aim of the Chinese Government is not to argue, but to bring arguing to an end.

China and India are two great countries each with its great past and future. Guided by the great ideal of the Five Principles of peaceful coexistence, the two countries have over the past few years joined hands and cooperated closely in defence of world peace. Today, history again issues a call to the peoples of the two countries asking them to make still greater contributions internationally to the cause of peace and human progress, while accomplishing tremendous changes at home. The task falling on the shoulders of the Chinese and Indian peoples of the present generation is both arduous and glorious. The Chinese Government wishes to reiterate here its ardent desire that the two countries stop quarrelling, quickly bring about a reasonable settlement of the boundary question, and on this basis consolidate and develop the great friendship of the two peoples in their common cause.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China avails itself of this opportunity to renew to the Embassy of the Republic of India in China the assurances of its highest consideration.”35

The above Chinese Note which was hard on matters of substance made such a massive Chinese case that Nehru and his advisors needed time to marshal evidence to refute it. The Indian ambassador to Beijing and Moscow were summoned to New Delhi for consultations. Also, a team of Indian historians led by Dr. S. Gopal, who later in 1960 participated in the border expert’s talks, was sent to London to try to strengthen the documentation of India’s claims. Before a detailed reply to Chinese Note was sent on 12th February, 1960, Nehru wrote to Chou on the 5th February inviting him to New Delhi for talks in the second half of March 1960

(4) The 12th February, 1960 Note of the Government of India to the Chinese Government