Introduction: Major Issues and Their Importance

O Goddess Ganga! You are the divine river from heaven, you are the saviour of all the three worlds, you are pure and restless, you adorn Lord Shiva’s head. O Mother! may my mind always rest at your lotus feet.

(Source: Sri Ganga Stotram)

“Gita and Ganga constitute the essence of Hinduism; one its theory and the other its practice.” – Swami Vivekananda

“The fool, dwelling on the bank of the Ganga, digs a well for water!” Such are we! Living in the midst of God – we must go and make images. – Swami Vivekananda

“The Ganga, especially, is the river of India, beloved of her people, round which are intertwined her memories, her hopes and fears, her songs of triumph, her victories and her defeats. She has been a symbol of India’s age-long culture and civilization, ever changing, ever flowing, and yet ever the same Ganga.” – Jawaharlal Nehru.

“I am convinced that everything has come down to us from the banks of the Ganga – astronomy, astrology, spiritualism, etc. It is very important to note that some 2500 years ago at the least Pythagoras went from Samos to the Ganga to learn geometry.” – Francis M. Voltaire

“If Ganga lives, India lives. If Ganga dies, India dies.” – Dr. Vandana Shiva

“The land where the Ganges does not flow is likened in a hymn to the sky without the sun, a home without a lamp, a Brahmin without the Veda.” – Jean Tavernier (Travels in India)

Our scriptures – even those, such as the Puranas, which evoke emotions towards the Divine by narrating His glories on the earth – have always begun with, and in their major part, espoused a living description of the earth – the mountains, the rivers, the continents – we inhabit. For us, the land of Bharatvarsha manifests, in form, the Transcendent, not only in its Avatars, it’s Rishis and its people, but also in the mighty Himalaya, which became the land for the union between the Divine and His Shakti, and its majestic rivers.

The flow of river Ganga from Lord Shiva to pervade the Three Worlds is not simply a religious narrative, but a manifestation of the Power and the Grace that went into the making of the living reality that is Bharat – the country, the ‘karmabhumi’ which is God’s laboratory destined to unite the Heaven and the Earth, the Spirit and the Matter, and to lead the world. Ganga is the lifeline of the Indian civilisation.

At a time when the humanity – ensnared by the traps of elevating Science to its own material godhead – is hurtling towards an inevitable disaster of its own making, the solution can be found only if India takes the lead, by revering once again the Supreme Shakti that guides Nature’s works. The secret is there in our own scriptures, and yet we opaquely insist on regarding Nature from the point of view of Western materialism. We apply same scientific and governance ‘techniques’ to find a solution to the ecological disaster staring us in face. The result is that we are making things go from bad to worse.

What solution can we give to the world, if we cannot save our own lifeline, the Ganga? ‘Namami Gange’ has a meaning behind it – a meaning that pervades both the religious and the material. This cannot be foolishly sacrificed by our illusions. Yet this is what has been, and is still, happening. Our failure to grasp the importance of Ganga will lead to a slow decay of the Indian nation.

The Ganga mission

The ‘Clean Ganga Mission’, also called the ‘Namami Gange’ has been among the major issues taken up by the Modi government since it assumed office, and especially by Modi himself. When Modi prioritized Varanasi and thundered out the importance of revamping the Ganga, he connected to the emotions of majority of India’s rural and semi-urban population.

However, currently, the Namami Gange is facing pressures for revival after nearly two years of not being able to deliver the desired outcomes. While well-intentioned, the project is coming into conflict with a number of other ‘clean energy’ initiatives, such as construction of hydroelectric power plants and dams, which will impede the flow of the river. It is also getting stuck because of bureaucratic hurdles and false technical solutions put forward by the bureaucracy.

Cleaning the Ganga: Ineffective solutions, misplaced priorities

Ganga runs for about 2500 km across five states and provides livelihood to almost 13 million people in India.1 The Ganga is also under threat from climate change. Due to global warming, the Gangotri glacier has been receding since 1780, with the UN 2007 Climate Change Report suggested that the glacial flow may completely stop by 2030, at which point the Ganga would be reduced to a seasonal river during the monsoon.2

There are currently two main issues facing the rejuvenation of Ganga – pollution or cleaning up the river, and, more importantly, ensuring that the flow of the river is not hampered by constructions of dams, barrages, interlinking rivers and other such ideas.

The Clean Ganga Mission has broad aims spanning:

- Cleaning the river by tackling urban and industrial pollution.

- Reviving ‘aviral dhara’ or continuous flow of water along stretches that have dried up over the years, covering the ‘minimum environmental flow’.

- Revamping river ecology, including ensuring the habitation for dolphins, gharials and other prized fish species.

- Making it an important inland waterway.

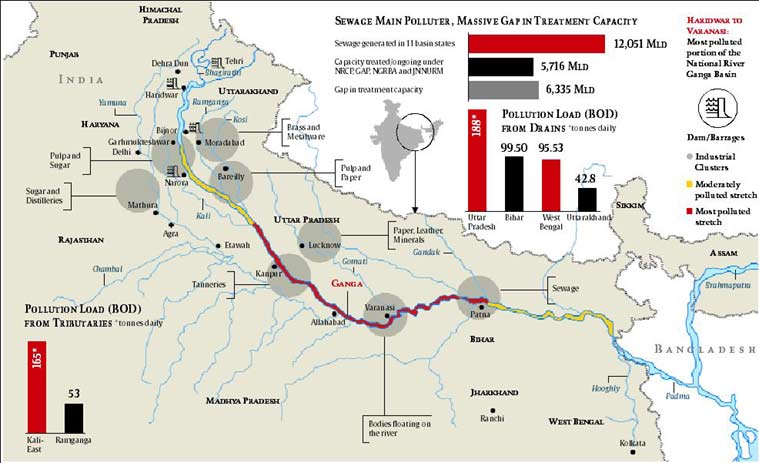

In terms of pollution facing the Ganga, from its journey from Gaumukh to the Bay of Bengal, the most polluting stretch is the 750 km falling in Uttar Pradesh between Kannauj and Varanasi. The state houses about 667 of the total 764 ‘grossly polluting industries’ that contaminate Ganga, out of which 442 are tanneries.3 The amount of waste that flows into Ganga spans the 500 MLD (Million Litres a Day) of industrial waste and about 2200 MLD of domestic waste coming out of the 50 major cities lying along Ganga’s main stem, in the absence of proper industrial pollution treatment systems and domestic sewage systems.4

The process of cleaning up the Ganga began in 1985 with the launch of the Ganga Action Plan – I. In 1993, it was revamped as Ganga Action Plan – II, and included Ganga’s tributaries – the Yamuna, Gomti, Damodar and Mahanadi. In 2009, Ganga was declared a National River and the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) was set up, while in 2010, the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) was established with the aim of ensuring that no untreated domestic sewage or industrial effluent would enter the river after 2020.

All of these plans and policies have focused on establishing infrastructural fanfare and spending money, while the implementation, on ground, was corrupt and lethargic. They established hundreds of Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs), which, unfortunately, continue to operate below capacity or lie dysfunctional, since, till date, only about 700 MLD of the total 2700 MLD of wastewater entering Ganga is treated, even as the Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) has also focused on establishing STPs.5 Even after the NGBRA was established by the previous UPA-II government, its meeting was held only three times in five years.

The NDA government which came to power in 2014 took a clean break from these piecemeal initiatives, by taking a major policy leap in sanctioning the Namami Gange project, with a total of 20,000 crores INR of funds allocated till 2019, and also set up state-level units to monitor the progress in the five states through which the Ganga flows.

| Time-frame | Fund allocation | Thrust areas | Activities | Implementation |

| Launched in 2014, it has 3 goals:- Short term (3 years).- Medium term (5 years).- Long term (10 years or more) | 20,000 crores for five years till 2019. | · Maintenance of flow.· River front development.· Capacity building.· Research and monitoring.· Biodiversity conservation.· Communications and public outreach. | · Revamping of existing STPs, and building new ones.· Sanitation cover for gram Panchayats.· Model cremation ghats.· Support system for planning and monitoring.· Maintenance of river flow.· Forestation, with native medicinal and plant species, near riverside.· Zero liquid discharge technology to recycle the wastewater.· Building 100 new crematoriums in cities and revamping old ones. | Establishment of the State Project Monitoring Groups (SPMGs) in five states. SPMGs report to the NMCG, which will release the funds to the SPMGs. These will release it to the executing agencies and monitor their progress. |

However, the progress on the ground is next to nothing. The solutions being adopted either reek of similar bureaucratic thinking that has historically pervaded this mission, or, are new variations of already-tried methods. Most importantly, what the current approach does not recognize is that ensuring the ‘aviral dhara’ or continuous flow of the river is more vital to the survival of Ganga than simply cleaning up the riverfront or outer development. Yet, several of the government projects clash directly with this aim.

The Aviral Dhara concept led to the declaration of the 132 km stretch between Gaumukh and Uttarkashi as an ecologically sensitive zone where no commercial activity would be allowed, during the tenure of the UPA government. But the government stepped in too late. While environmentalists believe that at least 32 per cent of the original waters of a river constitute minimum environmental flow – and that over 50 per cent is desirable – the Ganga’s minimum flow is barely around 5 per cent.6 Moreover, holding the river water in reservoir – the blocking of the river starts at the Maneri Bhali 1 project on Bhagirathi – and allowing only a minimum amount of flow has curbed the migration of several prized fish species, thereby reducing their numbers.

Some of the measures being considered by the government – such as the establishment of hydroelectric projects as a source of clean energy – are counterproductive to the local ecosystem of Uttarakhand. Moreover, with the government seeking to meet its ‘Electricity for all’ project deadline of 2022, it might give preference to establishing more power projects rather than restoring Ganga’s flow. In 2013, the Supreme Court had passed an order saying that no new hydroelectric projects will be established in the para-glacial region of Gangotri. But this was reversed in 2015, after a meeting of the PMO, which cleared six fresh projects, while the Uttarakhand government has identified another 450 potential projects, with 76 such projects already active in the para-glacial region, thereby leaving little scope for water flow.7

Maintaining the river flow or aviral dhara is the urgent need of the hour and the key to ensuring that there is, subsequently, cleanliness in the river. The latter is a civic issue, the former is key to the survival of the country’s life. An NGO, Yamnuna Jiye Abhiyaan, claims to have spent 30 years cleaning the Ganga and 20 years with Yamuna, and the river went from bad to worse. For, the mistake was in believing that simply focusing on cleanliness or fixing the sewage system would restore the river’s health, without doing anything about factors such as dwindling flow, artificial barriers, loss of catchment vegetation, encroachments on its flood plains, massive extraction of sand from its banks, and power projects.

Main issues and action

The major problem with cleaning the Ganga lies in the excessive reliance on bureaucratic jargon and prescriptions – for which all governments, however well-intentioned, are culpable – since the bureaucratic mindset is just to use up or eat the funds indiscriminately if they are available, augmenting both outright monetary corruption and an illusion of work being done. For instance, every year dead bodies are thrown in the Ganga, despite a UP High Court order prohibiting such dumping and the UP government providing a grant of Rs 1,600 for the cremation of every unidentified body. This is because the electric crematoriums rarely function due to corruption, as contractors cut off power, supply of firewood, with buying wood proving too expensive for many people. Sometimes, the police also dumps bodies into the river to pocket the grant.*

This kind of an unchecked mindset, combined with the present generation’s disregard for the cultural value of Ganga and its vital role in sustaining this country, results in corruption and inefficiency on ground. For, no one person can be held accountable for the river degradation, while no one has interest in committing to the river cleaning because everyone will benefit from the outcome. It is a typical selfish, logical thinking which characterizes this generation, while excessive reliance on techniques of project management keeps giving us false assurances that we are doing something.

That is why, despite the numerous ministries, departments, bodies, courts and NGOs fighting for the cause of Ganga, nothing much has been done to revamp the river. The corporate houses in the country have shown no interest in funding the project under Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). In fact, among all projects of the Modi government, the Swachh Bharat and Namami Gange have received least amount of funding from private companies in the year 2014-15.

The government action, so far, has spanned regulatory action against polluting industries, heavy monetary investment in the mission (of nearly 3 billion USD over a period of five years, combined with ambitious targets) and looking towards past national and international river rejuvenation projects to get the Ganga mission on track.

Many NGOs have decried the technocratic solutions – such as the IIT report on the Ganga River Basin Management Plan, and the recent draft plant, in December 2015, released by the Central Pollution Control Board which is based on a segmented approach to clean Ganga, establishing a differentiated approach for each area – which advocate building more mindless infrastructure and technology. Instead, one of the leading advocates on Ganga – the Ganga Mahasabha led by Swami Jitentranand – has been rooting for punitive solutions that can implement strict action, such as a National River Conservation Act and the setting up of a National River Protection Force, apart from demarcating land on either bank of the Ganga that would belong to the river and be unavailable for construction.8 Although, even with the right laws, implementation would be tough, given that water is a state subject.

In terms of current action on ground, the following action has been taken:

First, the government has acknowledged corruption as a problem, tightening rules, improving enforcement and closing down more than 100 leather tanneries – a significant step, given that about 200 tanneries had been operating in Kanpur without licenses.9 In the past, the companies never took seriously the need to curb liquid effluent discharge, set up common effluent treatment plants and install new technologies. But now, every tannery had to install its own effluent treatment and chromium recovery plants.

Second, in terms of international missions, the government has enlisted the help of Germany, taking lessons from Rhine rejuvenation. The Rhine is Europe’s longest river, rising in Switzerland, passing through Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France and Holland, and emptying in the North Sea. In 1986, the river became massively polluted in the aftermath of a chemical reaction at the Sandoz chemical plant in Basel and was revamped as a result of the intensive steps undertaken by the International Commission for the Protection of Rhine.

In terms of national missions, the government is also taking lessons from past Ganga missions. Even though the Ganga Action Plan that began in 1985 also set up Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) with a capacity of treating about 1000 million litres of sewage per day, it was a failure because of lack of cooperation and maintenance by states and municipal authorities. These erstwhile plants exist today too but are either functioning below capacity or not functioning at all. Due to procrastination in land acquisition, adverse weather conditions, court cases and want of funds, many sewage treatment plants sanctioned between 2008 and 2010, are yet to take off.10

Excessive reliance on the treatment of sewage has done us no good. Even though, as acknowledged by all, a major roadblock is the issue of sewage discharge into the river. Yet, nothing concrete has been done so far to manage the massive waste disposal from all the cities located alongside the banks of the river. This is despite the fact that a significant amount of funding from the scheme is going into the construction of sewage treatment plants at the urban centres along the river-side – a move that might prove to be detrimental to river conservation as it is related to urban waste management.

Today, the government is relying on corporates to do urban sewage management work more efficiently, in terms of capacity-utilisation and maintenance of STPs. Since they will be required to maintain the plants for a period of 15 years at the very least, the government will only provide the initial funding for infrastructure, while the rest of the costs and profit will be utilised through annuities over the 15-year period. How far this incentive system will work is yet to be seen. Besides the reluctance of Indian companies to contribute meaningfully to the mission, the step constitutes only a very minuscule part of the deeper, mammoth challenge facing us.

But urban sewage is only one form of pollution. The major problem of rural sewage remains unaddressed. With about 1650 Gram Panchayats dotting the banks of Ganga and majority of rural population defecating in the open, the government has a task on its hand to ensure the proper treatment of rural sewage. Only a third of the total area of Varanasi is actually connected to a sewer. Rest of the waste goes directly into the river.

In terms of more productive solutions to deal with rural sewage, the government plans to test biological methods, by adopting a model tried by a local spiritual leader, Baba Balbir Singh Seechewal, in cleaning the Kali Bein rivulet in Punjab in 2007. The steps involved segregating solid and liquid waste, composting solid waste, treatment of waste water through oxidation ponds or lagoons that break the organic matter in the waste for decomposition by bacteria and allow the growth of algae in the pond, and then the use of treated water for irrigation. The practice of this has infused a sense of common participation and ownership of the rivulet, over the years.

Third, in terms of immediate action, the government plans to award contracts cleaning solid waste from the surface of Ganga, across the five Ganga basin states of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal, aiming to begin the cleaning process by the end of June 2016. However, floating solid waste removal is the easiest process, resulting in only a visual make-over and is only supplementary to the process of treating water polluted by rural, urban and industrial sewage and effluent inflow.

Finally, another solution being floated by the government is that of interlinking of rivers – a move that could prove detrimental to Ganga rejuvenation. It cannot work unless the rivers have sufficient flow. The step could obstruct the natural ecology of rivers. Dams would not help to add river flows in the Ganga basin – which is topographically flat. These dams could also threaten the forests of the Himalayas and impact the functioning of the monsoon system and lead to serious climate change concerns.

Already, the construction of hydropower projects, – around 450 such projects in Uttarakhand have affected the flow of 53% of Bhagirathi – the ongoing tunnelling and mining in the Himalayas, and the government’s plans of interlinking rivers is spelling an increasing water disaster for the country.

Searching for solutions

Solutions to clean Ganga will not be realized if we approach the issue technocratically. As Rakesh Jaiswal, a Kanpur activist agitating against the pollution from leather tanneries, pointed out in an interview, “We have the science and technology, the talents, the manpower: everything is there. What is missing is honesty and dedication.”11

During the colonial period, the British rulers allowed, in 1916, a historic agreement, at the insistence of Madan Mohan Malaviya, while they were building the first Ganga canal, by which all Ganga projects planned upstream of Haridwar would have to seek the consent of the Hindu community first.12 However, even as this captures the true value of Ganga, this rarely happens, with even the current government not going all the way in focusing on Ganga.

But in post-Independence democratic India, where elections rule the roost, revamping the Ganga has become a political project. The idea of cleaning the Ganga first came during the 1972 ‘First Earth Summit’ at Stockholm, when PM Indira Gandhi was shown how the Stockholm River was decontaminated. It was later taken up by Rajiv Gandhi and found prominent resonance in Congress’ election manifesto. The two UPA regimes followed up the project and did some piecemeal action, and now, the NDA government has taken up this issue prominently. But, though well-intentioned, they are falling into the same trap by not setting their priorities right and taking radical action.

In other words, it is the corruption and the inability of the government to enforce laws, and above all, of a sense of alienation of the new generation from the emotive and spiritual value of their national, cultural symbols. That is why despite the numerous efforts to revive Ganga, since the time of Rajiv Gandhi, there has been a progressive decline of the river. The present leadership, while definitely building on the technical know-how of previous government and of the international community, has made nationalism the overarching framework of the mission.

At the announcement of the mission in 2014, Modi declared, “Ma Ganga has called me…She has decided some responsibilities for me. Ma Ganga is screaming for help, she is saying I hope one of my sons gets me out of this filth…It is possible it has been decided by God for me to serve Ma Ganga.”13

The message correctly captures the immediate necessity of Ganga rejuvenation, and should not be allowed to fall into false solutions, corruption and lethargy. The living reality of Ganga captures the growth and sustenance of Indian civilisation and nation. They are the one and the same life.

To be continued…

References:

- Sinha, Amitabh. The Indian Express. January 13, 2016. http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/simply-put-aims-and-hurdles-of-cleaning-the-ganga/ (accessed June 9, 2016).

- Nair, Prabhakaran KR. The Hindu. October 31, 2014. http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/what-will-it-take-to-clean-the-ganga/article6552936.ece (accessed June 13, 2016).

- Malhotra, Sarika. Business Today. April 10, 2016. http://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/features/why-the-ganga-cant-be-cleaned/story/230439.html (accessed June 12, 2016).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rowlatt, Justin. BBC News. May 12, 2016. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-aad46fca-734a-45f9-8721-61404cc12a39 (accessed June 9, 2016).

- Aswal, Devender Singh. The Pioneer. May 23, 2016. http://www.dailypioneer.com/columnists/oped/rejuvenating-the-river-ganga.html (accessed June 9, 2016).

- Rowlatt, Justin. BBC News. May 12, 2016. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-aad46fca-734a-45f9-8721-61404cc12a39 (accessed June 9, 2016).

- Malhotra, Sarika. Business Today. April 10, 2016. http://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/features/why-the-ganga-cant-be-cleaned/story/230439.html (accessed June 12, 2016).

- Rowlatt, Justin. BBC News. May 12, 2016. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-aad46fca-734a-45f9-8721-61404cc12a39 (accessed June 9, 2016).