The past year has seen a rise in the spate of violence – both psychological and physical – against women. It has, however, been accompanied by increasing sensitization and resistance among women. The most prominent events of the past year have centred around the temple entry movements led by women in major parts of the country, election of a first-time all-women’s Panchayat in Haryana through the rising demand for qualified and educated women, contestation of religious injustice through the Sharaya Banu and other cases seeking reform of Muslim Personal Law, and the protests following the recent brutal rape cases in Kerala.

The silent uprising for the empowerment of women has been a gradual process, which has been unfolding since the protests for a strong legal bill following the Nirbhaya rape case of 2012. However, in the past year, that process has accelerated. During the previous regime of the Congress government, the legal action against sexual harassment through the Justice Verma Committee Report occurred after a lot of protests, tribulations and tears, with the government continuing to drag its feet in taking action. However, this government has been proactive in promoting the cause of women empowerment. And the unlikely, and inadvertent, agent of change is Maneka Gandhi.

By the virtue of being the Minister of Women and Child Development, and by the sheer fortune of being a part of the proactive Modi cabinet, Mrs Gandhi has found herself in a spot where taking policy action has become a necessity. As a result, the Ministry departments and divisions in Women and Child Development are facing the same choice that every bureaucrat is facing, under the current government – come up with policy work or else face a negative performance stigma. This is now beginning to show some results, albeit at a purely superficial level, as yet.

The policies of the government send out a clear message that they treat women as individuals – as active contributors to the system, rather than as a weak group demanding welfare dole-outs.

The Disempowering Logic of Welfare

This is radically different from the approach of the Congress-led government. The UPA’s whole economy, whole approach towards welfare and governance and the whole treatment of “marginalized” sections of society, was based on subsidies – throw money and legal bills at the problem and divide them along their community lines. It was a subsistence economy oiled by the wheels of sly political expediency. In case of treatment of women, it allied with intellectuals to further weaken their position in society, by showing apathy towards innumerable women engaged in agricultural and informal sectors by not ensuring equal sexual division of labour, by creating vicious Parliamentary politics through the debate on 33% reservation for women and by generating unworkable policies for the girl-child and adolescent girls that actually ensured that they became a liability and an opportunity for their parents to earn money. It is unfortunate that majority of the UPA-era policies promise monetary and material benefits to the parents in return for keeping their daughters well. These policies – a brain-child of university academics – were doomed to failure right from the start, while the very idea of 33% reservation made it look as if women are second-class citizens that are taking away rather than contributing to the system.

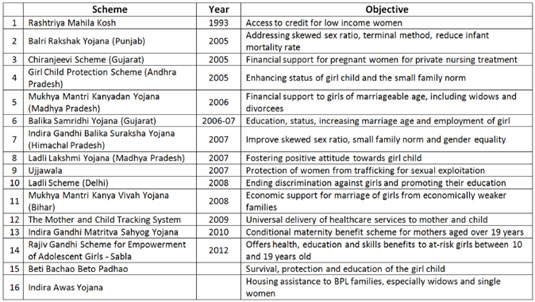

The major policies (refer to Table 1 in the Appendix) simply enumerate the aims, but the detailed conditions invariably try to ensure compliance by offering some kind of material benefits or incentives. Existent policy responses by the government adopted three approaches: (1) bans on the use of technology for sex-selective abortion for non-medical purposes; (2) financial incentives for parents to raise daughters; and (3) advocacy and media outreach to encourage parents to perceive girls to be as valuable as boys. The last mode was the least used by the previous government and the most used by the present government.

There are major problems with these welfare schemes:

First, are we more concerned about addressing the image of the state in question by talking about skewed sex ratio, while not caring about the actual implementation and the amount of funds transferred? This is akin to throwing money at the issues, without really addressing them.

Second, these schemes, even as they disburse questionably low funding, have also tied up the benefits of the scheme with explicit population control objectives. By instituting conditions like the small family norm, these schemes are presenting poor families with uncomfortable choices. For instance, one of the conditions of the Bhagyalakshmi Scheme is that in case the benefit is to be extended to a third girl child the father or the mother should have undergone a terminal family planning method.

Third, the welfare matrix constructs an image of the woman as a passive beneficiary of government spending, without any active contributions to the society, the economy and the politics. This is far from the facts. According to research1, direct land transfers to women are likely to benefit not just women but also children. Evidence both from India and from many other parts of the world shows that women, especially in poor households, spend most of the earnings they control on basic household needs, while men spend a significant part of theirs on personal goods, such as alcohol, tobacco, etc.

Fourth, the teeming welfare schemes are at odds with the deteriorating social condition of women. According to data2, the overall sex ratio of the population in India decreased from 972 female (per 1000 male) in 1901 to 940 in 2011. Child sex ratio fallen from 945 girls per 1000 boys in 1991 to 927 in 2001 and 919 in 2011. This is despite the existing number of policies to address the declining child sex ratio specifically.

Yet Another Flawed Belief: Can Mere Reservation Accomplish Empowerment?

Then there has been much discussion on 33% reservation for women in the Parliament. The popular perception is that it will lead to empowerment. However, besides the deeper flawed logic of this belief, even the facts on ground show a different reality.

The track record of women’s representation in political parties in India and their performance as candidates in elections, as well as their high electoral turn-outs, certainly indicates an immense scope for improvement and underlying potential for scaling up the empowerment outcomes. But the question before us is whether the perennial demand for reservation can actually be a workable solution here. Based on existing research, when we look at the experience of major countries in terms of ensuring political representation, the following central points emerge:

First, reservation, as the Pakistan experience shows, leads to the creation of a glass ceiling, wherein women contest only the seats reserved for them, leaving the rest of the general seats to the male candidates. Political parties are afflicted by such a dynamic.

Second, the policy of implementing voluntary quotas by political parties has worked very well in countries like South Africa, Germany and Sweden.3 With even one political party voluntarily implementing quotas for women within its organizational structure, an enabling environment is created for positive spill-over effects for other parties to follow that route. In India, where the major national parties unfortunately compete in not giving adequate representation to women in their internal party structures, such an approach might yield positive outcomes. This is especially because, as the data already documented shows, regional parties have a much larger share of women MPs in their fold, showing that inter-party competition can drive organizational changes.

Finally, there is a need to cultivate a political culture that can be conducive to the development of strong potential women candidates. The experiment failed in Pakistan, thereby ensuring that reservation just became an ornamental formality. It is herein that we need to understand the linkage between political empowerment and economic contribution of women, as will be discussed in the next section. Unless women’s contribution to the economy is recognized through which women are acknowledged as agents, the policy of reservation will invariably end up constructing a rhetoric of women as passive recipients of welfare dole-outs, rather than active members of the political community crafting their own policy choices.

Moving on From the Old Rhetoric

Despite the flaws behind their fundamental thinking, these are kind of policies that the Congress regime has propagated over the decades. They have been responsible for major injustices suffered by the women, and the change could only come once the women actively protested against the government after the 2012 rape case. And the Nature let that too take its full course, since, beneath the drudgery and corruption, certain ideas needed to be realized in the public thinking. Now that time is up. The new women’s uprising even broke away from the so-called women’s movements and NGOs that have existed in no rare number in India.

The current government is both a harbinger of change and has no choice but to be more ‘productive’. The first stirrings of the new shift are already visible in the India of today in the dual form of institutional change and social change. In terms of institutional change, it is visible in the recommendations of the draft National Policy for Women, 2016, which will be revised from the 2001, to keep pace with the changing realities. Instead of social welfare dole-outs, the thrust of the new policy clearly recognizes women as equal economic agents to fight ‘social prejudices and stereotypes’, by advocating measures like overhaul of personal laws to facilitate gender equality, criminalisation of marital rape as a human rights issue, rights of sex workers and the transgender community, recognizing the validity of pre-nuptial agreements in order to ensure that divorced women get their due, recognizing the validity of dependent care paid leave for all employees to reduce the burden of unpaid care falling on women, and new forms of sexual abuse through technological mediums.

Even though all of these recommendations have their flipside and the working of actual policy may produce many grey areas for women, yet what is common to all is the shift in public policy, in recognizing women as independent contributors to the system. Even where the policy seeks to give relief from entrenched stereotypes, it does so by vesting women with rights rather than favourable entitlements.

In social practise and change, this is supplemented by the massive silent uprising that has taken place among the women across the country, through issues such as the reinforcement of the woman voter, temple-entry protests across a series of reputed temples in the South, election of a first-time all-women’s Panchayat in Haryana through the rising demand for qualified and educated women, contestation of religious injustice through the Sharaya Banu case and the protests following the recent brutal rape cases in Kerala.

Who would have ever thought that in the remote villages of Haryana, men would someday actively search for well-educated women to take as brides, making qualifications the main criteria of marriage? This change was possible only after the implementation of the Panchayati Raj Bill, 2015 by the BJP-led Khattar government in the state. It made matriculation an essential criteria for general candidates and passing of class VIII for women candidates, besides, payment of electricity bills, working toilet, disposing off bank loans and not being chargesheeted in criminal cases with imprisonment of up to 10 years. Supreme Court upheld the Bill in its judgement on 10th December, 2015. Rajasthan had passed a similar Bill in Panchayat elections in 2014.

And the incentive because of which people are preferring educated women is also not negative – it is an incentive to contest elections, rather than some typical monetary dole-out. The criticisms against it are quite weak, since the policy will only exclude a select batch of current generation women, but will ensure a secure future. It will – and already has – also incentivise both modern and traditional parents to get their girls educated.

Future Perspective

Despite this change on the ground and the actual empowerment of women that is now happening, the future looks tough. Women are becoming an equal part of a modern society that is increasingly sinking under the load of its continuous needs and desires, in the process destroying their own environment and institutions and also creating personal psychological problems for themselves.

Till now, it has been an easy ride for the feminist movement. They simply had to fight an enemy whose presence could be palpably felt – it is much easier to contest obvious structures like patriarchy and much more difficult to see the subtler challenges. The challenges that are facing women today are much more psychological and subtle in nature – a natural outcome of the fact that overt prejudices are being overpowered through a rise in women’s collective consciousness. These challenges have transformed from being general and collective to being a lot more individualised, while the movements continue to treat women’s challenges as a mere matter of general material institutional reform.

What public policy and its petitioners in the form of social movements fail to recognize is that welfare, as understood through the broadened idea of integral well-being, cannot be treated as a metric that can be ensured through the facilitation or erosion of certain sociological indicators. Rather, as progress is made, challenges don’t disappear but keep becoming more subtle and difficult to navigate. Women stand at precisely such a turn today.

Appendix

References:

1. RGICS. 2014. Women’s Rights and Challenges in India. Issue Brief, New Delhi: Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies.

2. RGICS. 2014. Persisting discrimination and deprivation. Issue Brief, New Delhi: Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies.

3. Pathak, Junty Sharma, and Mahima Malik. 2014. “Women and Political Participation in India.” RGICS Policy Watch, May 26: 4-9.