“War is no longer, perhaps, a biological necessity, but it is still a psychological necessity; what is within us, must manifest itself outride.” – Sri Aurobindo (CWSA 25: 611)

The idea of a country waging primitive, expansionist warfare against an independent nation has been unthinkable in more than half-a-century at least. The aftermath of the Second World War had created a different and new world order where respect for the sovereignty of nations was the foremost principle of mutual co-existence. The principle of war has not gone but has adapted itself subtly to the changing circumstances of the world. However, the war in Ukraine is a departure from the norms of the world we are living in. It takes us back to the primitive thinking – on which the Russian assumption is based – that brute physical power of a nation-state will triumph over a weaker one, and that a weak adversary country can simply be bombed out of existence.

Signifying one of the gravest crises facing the world since the end of the Second World War, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought with it complete destruction, loss of lives and has unleashed immense psychological insecurity and suffering among the people of Ukraine and the rest of the world. All of this was done simply to satisfy the assumptions and diktats of a dictator. Signifying a great setback to the precarious and superficial post-Second World War rules-based international order, the arbitrary Russian invasion of Ukraine has ushered in an era of creeping insecurity among nations. The Russian invasion of Ukraine seems to legitimize the idea that the sovereignty, independence and existence of a nation can be attacked at the whim of a larger power, making it necessary that Russia be defeated and taught a lesson.

Ukraine and Russia: A Brief Background

Modern-day Ukraine is a country that has been independent for only 23 years, being under foreign rule since the 14th century (Kissinger 2014). Modern-day Russia, Ukraine and Belarus trace their ancient ancestry to a federation called Kyivan Rus’. It was a federation of East Slavic, Baltic and Finnic people of eastern and northern Europe, with its capital in Kyiv. Christianity was made its state religion in 988 AD. After its decline and incorporation into various empires through intervening centuries, in 1569, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was formed (IE 2022). The modern Ukrainian identity emerged as a revolt against the Polish-Lithuanian empire in 1648, when the Ukrainian state of Cossack Hetmanate was formed in what is presently central Ukraine. In around 1748-50, Russia’s Catherine the Great absorbed the entire Ukrainian state into the Russian Empire. Despite the Tsarist policy of Russification, there was not much outright conflict and the Ukrainians flourished in Russia and fought alongside Russia in the First World War (IE 2022).

However, the seeds of Ukrainian nationalism were strong. In the middle of the 19th century, to accommodate the growing Ukrainian nationalism, Russians formulated the concept of a tripartite Russian nation, consisting of the Great Russians (Russia), Little Russians (Ukraine) and White Russians (Belarusians). In the aftermath of the First World War, due to the decimation of the Tsarist Empire, several small Ukrainian states and factions, including the Communist one, fought for supremacy, with the independent Ukrainian Republic being proclaimed in 1918. In 1920, Ukraine became a part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The intervening years between 1918 and 1920, gave Ukrainians a taste of independence in modern times. As a result of this independent streak, Bolshevik Russia was forced to grant Ukraine the status of an independent nation, even though it was a part of the USSR.

After being a part of USSR for many decades, in the late 1980s, with the rise of a new liberal, global world order, the cultural and economic dominance of the West, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the inevitable weakening of Communism, Ukrainians had already started demanding that Ukraine leave the USSR, with the Ukrainian youth leading a ‘Granite Revolution’ to prevent the signing of a renewed agreement with a nearly finished USSR. In 1991, the USSR was dissolved and after that Ukraine’s Parliament adopted its Act of Independence, with Leonid Kravchuk becoming the country’s first President. Ukraine never ever officially ratified the agreement to become a part of Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) created in 1991 – a symbolic, cultural successor grouping to the USSR.

Russia has always perceived Ukraine to be an integral part of itself – notwithstanding the Ukrainian objection to the Russian version of history – from the Tsarist regime to the Bolsheviks to Putin. Lenin was even quoted as saying that, “For us, to lose Ukraine would be to lose our head.” In a recent article titled ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’ (July 2021), Putin advocated that Russians and Ukrainians were one people who shared a common “historic and spiritual space”.

Presently, Ukraine, located in eastern Europe, is the largest country in Europe after Russia, bordered by Russia to its northeast, east and southeast; Black Sea to the south; Moldova, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland to its southwest and west and Belarus to its north.

It is also the poorest country in Europe in terms of GDP and GNI per capita. Much like Russia, it has been riven by corruption and run by a few corporate oligarchs. It has a population of around 44 million people, of which around 78% are Ukrainians and around 18% are of Russian ethnicity. The Russian linguistic ethnicity population lives mostly in the restive eastern regions of Ukraine, which share the border with Russia, while the western region speaks Ukrainian. The country is also divided by religion, with the Catholic religion being widespread in the western parts of Ukraine, and the Russian Orthodox Church being widespread in the eastern region. While Russia and Ukraine had a confrontation over Crimea, Crimea was not historically a part of Ukraine. Crimea, which has a majority Russian population, became a part of Ukraine only in 1954, when Nikita Khrushchev, a Ukrainian by birth, awarded it as part of the 300th-year celebration of a Russian agreement with the Cossacks (Kissinger 2014).

Over the last eight years – following the Russian annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 – Russia has fueled an armed insurgency and separatism in the eastern Donbas region of Ukraine, mainly in the provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk, thereby keeping Russia and Ukraine in a continuous state of war. Ukraine’s President Zelenskyy had attempted to reach some kind of a solution for the eastern provinces in 2019, through the Steinmeier Formula which proposed elections in the Donbass region under the Ukrainian legislation, in accordance with the Minsk Agreements of 2014 and 2015. It was proposed that if the supervisory body – Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) – found the elections free and fair, then Donbass will be accorded a ‘special status’ and Ukraine will have regained its borders. However, this attempt failed due to Ukraine’s insistence that Russia first vacate the region of its military presence and due to protests by Ukrainians who saw the Steinmeier Formula as a surrender to Russia.

The Russian recognition of the two eastern provinces as separate from Ukraine was announced immediately prior to Putin’s launch of the ‘Special Military Operation’ which involved the invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, 2022. The operation/invasion was avowedly launched to liberate these provinces from Ukraine, much like what Russia did in Crimea in 2014.

The Genesis of the Invasion – Historical Background

“For the West, the demonization of Vladimir Putin is not a policy; it is an alibi for the absence of one” –Kissinger (2014).

This statement describes well the state of US policy towards Russia – an economically and militarily broken country – since the collapse of the USSR in 1991. In the aftermath of the Cold War and the dissolution of the USSR, a weakened Russia had sought to build new bridges with the US and Europe. Ideally, the US should have perceived no threat from Russia, and yet it has used Russia as a convenient bogey to advance its commercial defence interests in Europe, especially through Ukraine. This unpleasant truth is one of the principal reasons why Russia and the West have had antagonist relations, with Ukraine often becoming a ground for proxy warfare between them. While the US may, by default and not by principles, be standing on the right side of history today, it must also be acknowledged that the US has been one of the key ideological architects of the present war.

This is evident in the persistent US efforts to seek confrontation with a weakened Russia through the last 30 years, with Ukraine being an important pawn in that geopolitical calculus. Incidentally, much of this confrontation has been spearheaded by Mr. Biden under his various positions in the US administration.

In the aftermath of 1991, a series of goodwill gestures were made to signal the beginning of a new relationship between Russia and the West. Arms reduction treaties and various agreements were signed to foster lasting peace. However, successive US administrations have not been able to work with Russia citing petty reasons for the same, such as domestic disturbances in Russia, and Russia’s sliding into dictatorial concentration of power under Boris Yeltsin and then Vladimir Putin after 1999.

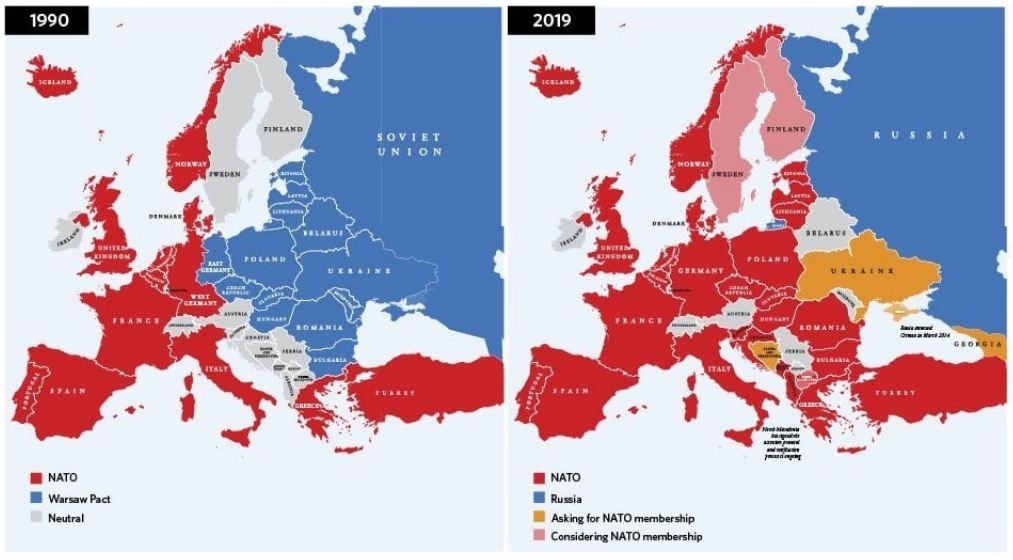

At that point of time, both Ukraine’s and Russia’s key concern was guaranteeing their respective security. For Russia, this mainly translated into the assurance that North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) created in 1949 to ‘contain’ the USSR would – if not disbanded altogether, having outlived its purpose – at least not spread to the countries in eastern Europe, thereby threatening Russian security. Russia’s Gorbachev had received the assurance from the West that the NATO alliance will “not move 1 centimetre further east” (Mathew 2022). In return, Russia accepted the democratization and independence of eastern Europe.

Logically, NATO – created to counter Soviet Union during the Cold War – had outlived its purpose, and yet the US refused to disband it. The US not only refused to disband NATO, but also made it the prime focal point of its entire Euro-Atlantic security architecture. The plea made by the West was that NATO would work to address Russia’s security concerns, and yet in the same breath the West claimed that Russia has no security concerns because NATO is a purely defensive organization, and hence not a threat to Russia. This superfluous argument hardly did any credit to the West. For, contrary to what the West claimed, NATO expanded aggressively in eastern Europe.

Thus, despite assurances made by US to Russia’s Gorbachev in 1989-90 that NATO would not expand eastward, the US-led NATO did expand in eastern Europe, taking in new countries, including some that were a part of the erstwhile USSR, taking the total number of its members to 30. This expansion began from 1997 under the Clinton administration, with Mr. Biden personally supervising it. In 1999, Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland became part of NATO. In 2004, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia joined NATO. Albania and Croatia joined the alliance in 2009. Montenegro joined it in 2017, and North Macedonia in 2020. During most of these phases Mr. Biden has been at the helm of affairs in US in various capacities, from Secretary of State to Vice-President to President of the US.

This expansion took place because of Russia’s ingrained apathy and threat perception with regard to NATO, reminding the former that in the event of another European war, Russia would be left with no buffers and would be completely isolated. And US’s fickle track record could not be trusted.

A Questionable Record: Thriving on War:

“War is no longer the legitimate child of ambition and earth-hunger, but the bastard offspring of wealth-hunger or commercialism with political ambition as its putative father” – Sri Aurobindo (CWSA 25: 494).

In the Russia-Ukraine war, history will judge Russia for the disastrous blunder it committed. It will also judge the US for instigating this war. Russia’s insecurity about NATO stemmed not just due to its expansion in eastern Europe, but also due to its practical track record which belies its claim of being a ‘defensive organization’. History bears this out. Russia had noted how the NATO had militarily intervened and bombed Yugoslavia, a non-NATO country, and took sides against the Serbs who were Russian allies and did so without sanction from the UN Security Council. NATO’s regime-change exploits in Libya and Afghanistan – which they liked to term as ‘nation-building’ instead of invasion – killing thousands of civilians, were also well-known. Its record in other third-world countries has been hardly any better.

Indeed, the US has always been the architect of warfare in the contemporary era. According to American historian Peter Kuznick, “War is big business for US.” It has used war as a means for the fulfillment of its commercial interests. NATO’s military record fortified the Russian concern that it does not want NATO at its doorstep. Russia’s “security concerns” are not a recent plea manufactured by Putin as an excuse to invade Ukraine, but are being reiterated by Russia for the last three decades. Among others, Biden’s CIA director, William Burns, has been warning about the provocative effect of NATO expansion on Russia since 1995. Russia had warned multiple times that NATO expansion is a red line for it which may force it to resort to war or military action. Despite this, the US placed American rockets in Poland and Romania and armed Ukraine.

In June 1997, 50 prominent foreign policy experts signed an open letter to Clinton, saying, “We believe that the current U.S. led effort to expand NATO … is a policy error of historic proportions” that would “unsettle European stability.” (Suny 2022). In 2008, Burns, the then American ambassador to Moscow, wrote to US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice: “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). In more than two and a half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.” (Suny 2022). George Kennan, who was the architect of the American Cold War era policy of containment of communism, had warned in the 1990s that NATO expansion was “a strategic blunder of potentially epic proportions.” (Aleem 2022). British author and expert Anatol Lieven had said of NATO expansion that Russians had always “warned that if this went as far as taking in Georgia and Ukraine, then there would be confrontation and strong likelihood of war.” (Aleem 2022).

Despite this, NATO has expanded aggressively. The continuous and steady expansion of NATO eastward, the US support for the ‘colour revolutions’ in eastern countries like Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004, and Kyrgyzstan in 2005, and, US support for Georgia’s and Ukraine’s desire to join NATO fomented much distrust.

The Situation became particularly tense in 2008 after the West gave an ‘assurance’ to Ukraine and Georgia that they will eventually be made members of the NATO – without specifying any timeline or concrete commitment for the same. This even led to Russia going to war against Georgia in 2008. The US’s facile assurance on which it did not plan to make good has been one of the principal causes which has enabled the West to prey on western and central Ukrainians’ hatred for Russia, making Ukraine an active ground for conflict between Russia and US.

In 2014, when Ukraine’s pro-Russia President, Viktor Yanukovych, was ousted by the West-supported Maidan protests or the Euromaidan protests, Russia annexed Crimea. Even more damning was the leaked phone call of the then US Assistant Secretary of State, Victoria Nuland, which revealed the US’ hand in the revolution and in government formation in Ukraine. Since 2014, Russia’s relations with the West have not recovered, even as NATO has continued to expand in the east.

In 2014, US’ Henry Kissinger had advised that Ukrainian politicians should stop becoming a pawn of the West or Russia and should, as the best way forward, seek reconciliation between the eastern and western regions of Ukraine. Indeed, he had suggested that “internationally [Ukraine] should pursue a posture comparable to that of Finland. That nation leaves no doubt about its fierce independence, co-operates with the west in most fields, but carefully avoids institutional hostility to Russia.” This balance could not, unfortunately be struck. And despite the high spirit of the Ukrainian people, their foreign policy was hostage to either the West or Russia, instead of being independent. Almost every country has had much worse internal contradictions and separatist movements, but an independent country would seek reconciliation between its deeply conflict-ridden internal parts, which Ukraine had not been able to do, all the more surprising given the fact that they share broadly the same racial and religious identity – an advantage not available to most countries.

After 2014, bitterness justifiably grew so much that things could have only deteriorated from thereon. Thus, after 2014, Ukraine has justifiably, out of concern for its own security and being in a state of war with Russia, conducted joint military exercises with NATO, received advanced weapons systems from the US, such as anti-tank missiles, and hosted NATO military units. In response, Russia has also left no stone unturned in actively fueling separatism and war in the pro-Russian eastern regions of Ukraine. The region already had majority pro-Russian population which was subject to persecution by Ukrainian authorities. The Minsk Agreements signed, in the aftermath of Crimea annexation, in 2014 and 2015 have been largely ineffective in stopping the war in Ukraine’s Donbass region.

Presently, Russia’s calculus is influenced by the fact that the three Baltic states, now part of NATO, share borders with Russia. Belarus and Ukraine are now the only countries – belonging to a past USSR sphere of influence – that are now outside the NATO. Russia considers maintaining a buffer between NATO and itself along its southern and western border as critical to its security. While a small country like Belarus has been somewhat managed by Russia, a hostile and much larger country like Ukraine poses greater problems. Russia claims that the scenario under which Ukraine joins NATO and gets the protection of NATO’s nuclear umbrella could make it a site for hosting missile launchpads within a few hundred kilometers of Moscow, and, together with Turkey, cut off Russia’s access to the Black Sea.

Putin had warned about the impending invasion since the last one year at least when Ukraine had issued a public threat that it will develop nuclear weapons unless it is allowed to join NATO. This public blackmail – which Russia saw as creating a fertile ground for Ukraine joining NATO – made Russia issue a statement saying that there will be military consequences unless this issue is resolved.

Failing to Cooperate

The immediate triggers of the present conflict had been brewing for at least about a year. Ever since the Biden administration took charge, NATO once again became a flashpoint in Europe. While US’s former President Trump had sought to scale back US role in NATO, arguing that Europe should take responsibility for its own security, Biden has reversed that policy.

Prior to December 2021, Russia had, for several months, been reiterating the warning that NATO should stop increasing its military deployments along Ukraine’s border with Russia. These demands were rebuffed by the West. In retaliation, Putin began to amass Russia troops along the border with Ukraine since December 2021, warning, for months, of making good on the threat of military action if NATO did not withdraw. In mid-December 2021, Russia had again presented demands to the West, including the US, concerning NATO withdrawal. Despite talks between Putin and Biden, the impasse continued.

Thus, from December 2021 onwards, Russia began amassing troops on the border with Ukraine, thereby raising the possibility of an invasion. Russia kept the troops – amassed at more than 130,000 – on standby, in a state of confrontation, even as it held a series of summits with the NATO, Germany, France, Ukraine and the US President, spanning more than two months. Despite such a long period of confrontation and talks, the two sides failed to break the impasse.

During these negotiations, Russia demanded the following –

First, it wanted an “in writing” guarantee from the West that NATO would not expand any further eastward.

Second, it wanted the removal of NATO troops from Baltic states.

Third, and most importantly, it wanted a guarantee that Ukraine would never join NATO.

The West had rejected all of the Russian demands as non-starters, leading to a deadlock in negotiations.

Russia’s Blunder

The failure in protracted negotiations led to Putin committing the present blunder of epic proportions, wiping out at once all international support for Russia. He invaded Ukraine in a ‘special military operation’ on February 23-24. Based on the crude idea of ‘might is right’, this blatant violation of a country’s territorial integrity found no takers in the international community. The subsequent votes that took place in the United Nations – at, both, Security Council and General Assembly – saw almost all the countries voting to condemn Russia for its actions. There were some like India and China who abstained. In order to show its neutrality, India also abstained from a Russia-sponsored resolution on the humanitarian situation in Ukraine.

However, despite the fact that the majority of the world’s countries have condemned the Russian act of invasion, the sanctions and refusal to do business with Russia have been endorsed only by some powerful Western countries.

Even the sanctions imposed by these countries are qualified, with the strictest sanctions being imposed by the United States – in areas where it is convenient to do so.

Sanctions Against Russia:

Military:

Ban on the export of dual-use goods – items with both a civilian and military purpose – imposed by the UK, EU and US.

As a result, Ukraine says Russia’s main armoured vehicle factory has run out of parts to make and repair tanks and a tractor plant has stopped production because of a shortage of foreign-made parts.

The UK is also imposing sanctions on Russia’s Wagner Group – a Russian private military firm.

Flights:

All Russian flights have been banned from US, UK, EU and Canadian airspace.

The UK has also banned private jets chartered by Russians.

Luxury goods:

The UK says it will ban the export of luxury goods to Russia. The EU has already imposed a ban.

The UK will also put a 35% tax on some imports from Russia, including vodka.

Targeting individuals:

The US, EU and UK have together sanctioned over 1,000 Russian individuals and businesses, who are considered close to the Kremlin.

Oil and gas:

The US is banning all Russian oil and gas imports and the UK will phase out Russian oil imports by the end of 2022. However, the US has refused to ban the import of critical Uranium from Russia. These imports made up about 16% of the US’s uranium supply in 2020 (Russian allies Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan provided another 30%). US’s oil and gas imports from Russia are minuscule, making the oil and gas sanctions easy to administer.

The EU, which gets a quarter of its oil and 40% of its gas from Russia, says it will switch to alternative supplies “well before 2030”.

Germany has put on hold permission for the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to open.

Japan has refused to put on hold its Sakhalin-2 LNG project with Russia, claiming that it is critical to its energy security.

Financial measures:

Western countries have frozen the assets of Russia’s central bank, depriving it of its $630bn of foreign currency reserves, causing the ruble to slump by 22% since the start of the year, leading to a rise in the price of imported goods and a 14% rise in Russia’s rate of inflation.

Some Russian banks are being removed from the international financial messaging system Swift, which is used to transfer money across borders. This will delay payments to Russia for energy exports. However, it is ineffective as Russia is demanding payment in rubles for trade to happen (BBC 2022).

As is evident, the scope of the sanctions, though wide, continues to be hampered due to lack of depth. While European countries may have symbolically condemned Russia at the UN, they have still been reluctant to go all-out in imposing sanctions.

US has refrained from sanctioning Russia in areas where it imports substantive amounts of goods, while oil and gas sanctions from Europe are not absolute and are contingent upon EU diversifying its supplies over a decade. US oil companies – such as Shell – had, even after the conflict, continued to purchase oil from Russia at discounted prices.

Japan has imposed facile sanctions on Russian individuals and entities, but has protected its energy interests by leaving that out of the scope of sanctions. In particular, Germany has been somewhat reluctant to stop oil and gas imports from Russia and decided to be strict about implementing financial sanctions only after the German public – around 100,000 people – took to the streets in massive anti-Russia protests. Germany’s energy dependence on Russia has been a major factor in influencing the German attitude. Russia provides 27% of the German energy supply, constituting around two-thirds of its natural gas consumption. If Russian supply were halted, European economies would be massively derailed, possibly even leading to a recession.

The majority of countries that had condemned Russia have refused to sanction it, including Turkey and Israel. Each country has, therefore, pursued sanctions as per its own convenience.

However, far more effective than the sanctions regime has been the supply of military equipment and weapons, which is the one area where the western support for Ukraine has been robust. In terms of indirect troop supply also, the situation has been supportive. While the western countries could not send troops directly to Ukraine due to fears of triggering a larger world war, they have been sending citizen-mercenaries to fight in Ukraine, many of them paid handsomely. The US also refused to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine (which would be interpreted as an act of war by Russia), refusing Poland’s offer to send fighter jets to Ukraine via Poland.

However, there are tens of thousands of troops being activated and deployed by NATO countries in Eastern Europe and military aid is in full flow. Since 2014, the US has committed over USD 3 billion in security assistance to Ukraine, which has considerably helped the country. In December 2021, a USD 200 million package was additionally announced to supply military equipment to Ukraine. During the course of this conflict, the US has further approved more than USD 1 billion in military aid to Ukraine, and a total of $2 billion since the start of the Biden administration.

The western supply of military aid to Ukraine has completely diluted Russia’s conventional military superiority over Ukraine. Conventionally, Russia – a world leader in missile technology, has amongst the mightiest armed forces in the world and outstrips Ukraine in almost every other aspect, such as airpower, armed personnel, tanks, armoured vehicles, artillery guns, naval vessels and submarines. However, the military equipment received by Ukraine from the West and Ukraine’s spirit of nationalism has considerably enhanced Ukraine’s military and strategic advantage.

The West has supplied Ukraine with some of the most advanced and powerful weapons systems in the world. These include:

Bayraktar TB2 drones:

Turkey began selling the TB2 drones to Ukraine in 2019. Turkish officials have refused to disclose how many, but independent estimates reckon Ukraine has up to 50 TB2s.

Switchblade drones:

This includes supply of 100 drones, also known as “kamikaze drone” that explode on impact.

Stinger missiles:

The aid includes 800 Stinger anti-aircraft systems in addition to more than 600 already promised. This type of weapon was seen as crucial to the mujahideen’s successful guerrilla conflict in the Soviet-Afghan war in the 1980s. Germany has also pledged to send 500 Stinger missiles.

Javelin missiles:

The Javelin is an anti-tank missile system that uses thermal imaging to find its target. The latest US package includes 2,000 of these missiles.

Portable anti-tank weapons:

The US is sending 6,000 AT4 portable anti-tank weapons. European countries include Germany, which has pledged 1,000 anti-tank weapons, Norway with 2,000, and Sweden, which has delivered 5,000.

Light anti-tank Weapon missiles:

The UK has sent 3,615 of these British-Swedish-made short-range next generation light anti-tank weapons, while US is sending 1000 of these.

Starstreak anti-aircraft missiles:

They are known to be the fastest short-range surface-to-air missile.

The advanced, unprecedented weapons supply and military aid to Ukraine and the nature of weapons provided ensure that Russia doesn’t stand a chance in conventional warfare against Ukraine. This supply is matched by Ukraine’s fighting spirit despite the suffering and devastation it is facing.

The Devastation of the War and the Will to Resist

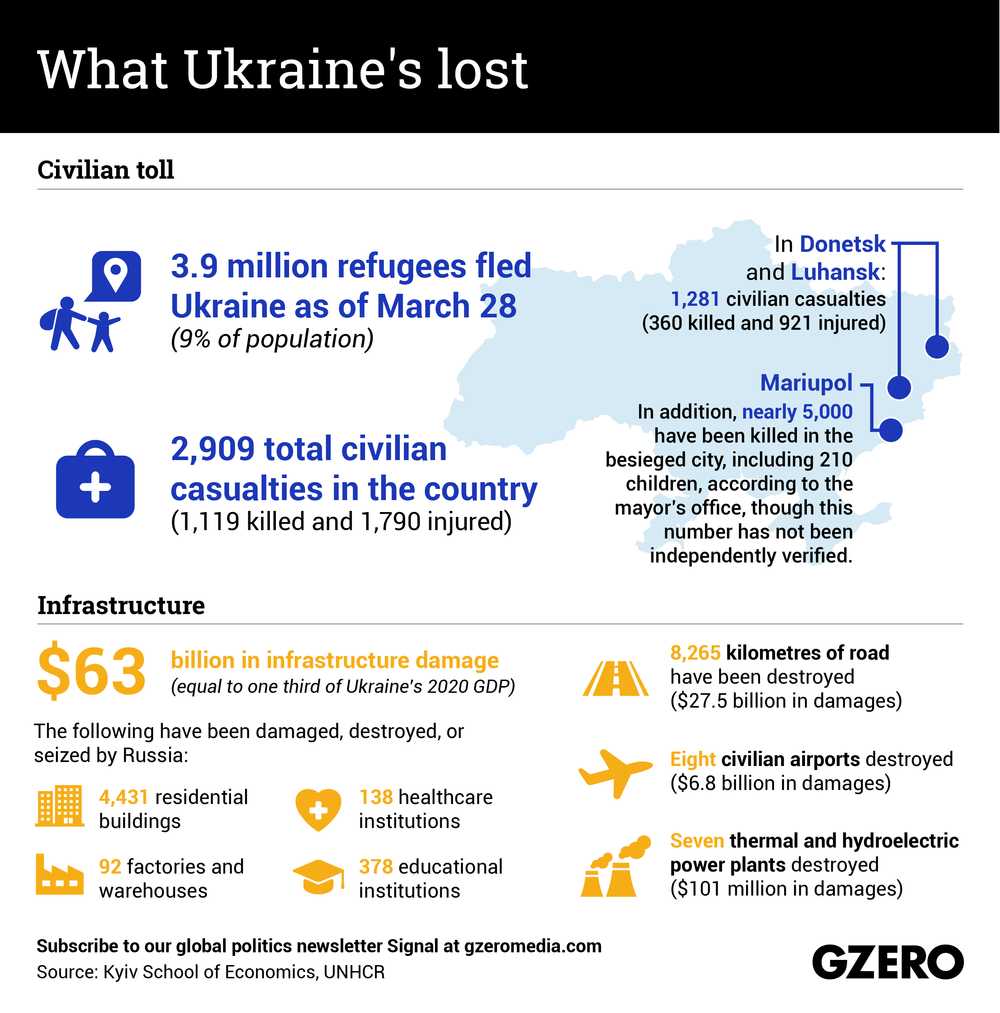

The untold amount of havoc, suffering and death wreaked by the Russian invasion will, according to UN estimates, result in one of the largest migrations in European history, if this war is prolonged. While more than 4-5 million people have already fled Ukraine, this number is projected to significantly increase in the event of a protracted war.

It is clear to the whole world that Ukraine has stood and fought Russia all alone in this war. It has displayed a level of resistance, national resolve and unity that has surprised Russia and the whole world. Instead of despairing, Ukrainians have fought back since the very beginning of the invasion. Their common and universal refrain is that they would rather die fighting than surrender to the invader.

Common citizens have readily taken up arms and turned into soldiers in the service of their country. It must be noted that Ukraine’s President has enforced a decree banning male people from the age of 18-60 from leaving the country and compulsorily enlisting in the military to fight in the war. However, much of the resistance has also been voluntary. Ukraine’s ‘international legion’ has also invited citizens from abroad to participate – in which various retired soldiers from different parts of the world, including India have joined. Foreign mercenaries are also being sent to the war in large numbers by the western countries. Even Russia has engaged mercenaries to fight in the war. The young are especially and readily willing to fight alongside the military. Ukraine has also enlisted its elite, albeit neo-Nazi, Azov battalion at the forefront of the battle-lines – the brutal battalion has been able to successfully repel Russia.

The war has brought to the fore the irrepressible spirit of the Ukrainian people, facing which even the invader is helpless. The attitude that they are ready to die and will fight till the last breath has effectively given Ukraine a much bigger psychological and material victory than an isolated and condemned Russia could ever imagine. It is this psychological impetus that is driving the Ukrainians – commons as well as soldiers – to repeatedly re-take even those cities and areas that Russia had conquered.

Due to the Ukrainian spirit of resistance and weapons aid to it, Russia has faced significant losses and its military and logistical resources are being stretched, placing it in a difficult position the longer the war continues. This supply is matched by the fact that Russia is facing unprecedented logistical difficulty, troop fatigue and losses on the battle-field. A Ukrainian newspaper, The Kyiv Independent, based on Ukrainian armed forces estimates, calculates that Russia has lost more than 12,000 troops (including 8-9 elite commanders), 58 planes, 83 helicopters, 362 tanks, 135 artillery pieces, 1205 armored personnel carriers, 585 vehicles, etc., as of March 10th. These figures have shown how Russia’s military superiority over Ukraine has been negated and was a big miscalculation on Putin’s part. It just goes onto show that psychological strength and integrity triumphs over brute physical force.

Confidence in Political Negotiations

This Ukrainian spirit and battle victories have also given Ukraine confidence in the negotiations. Thanks to the unity and nationalism of the people and the military aid flowing in from the West, Zelenskyy has been able to conduct negotiations with the Russian side on his own terms. Despite publicly declaring that Ukraine will not join NATO, Zelenskyy has refused to put this down in writing. He has also publicly stated that he is unwilling to discuss the status of the separatist eastern territories in the Donbass region, until Russia ceases the war first.

Russian position:

• Legal recognition to Luhansk and Donetsk provinces in eastern region of Donbass.

• Legal and constitutional change to commit Ukraine to neutrality i.e. commitment to not join NATO.

• Restriction on arms accumulation of Ukraine.

Ukrainian position:

• Written agreement for prior legal security guarantees from Russia and the West that Ukrainian sovereignty won’t be violated.

This deadlock – despite the costs of war for both Ukraine and Russia – is presently working in Ukrainians’ favour, due to their spirit of dying insted of surrendering, their superior position in the war and the support they have from the whole world. Ukraine’s refusal to give a guarantee in written about NATO in the negotiations and demanding Russia’s ceasefire first is the result of the newfound Ukrainian spirit of confidence and nationalism. It is also based on Ukraine’s legitimate demand that first Russia give a written legal guarantee that it will not attack Ukraine in the future. This is a very important position; for, anything that comes out of these negotiations will be useless if it leaves Russia to launch a similar attack few years later due to some imagined grievance or claims. In such a future event, Ukraine cannot possibly give a guarantee of neutrality or territorial concessions without getting its own protective guarantee in return.

Unless Russia gives a guarantee to not attack in the future, the negotiations will remain where they are – and understandably so. Thus, despite several rounds of negotiations, first in Belarus and then in Turkey, the deadlock continues. It is obvious that, in these negotiations, Ukraine is negotiating from a superior psychological position of strength and determination to secure its permanent interests – a strength which is buttressed by the support of the entire world behind it.

India’s Position and Lesson to Learn

In this entire conflict, India has predictably been placed in a difficult position – similar to China. While it is disturbed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and has used sharp language to condemn the violation of Ukrainian sovereignty, yet it has successively abstained – five times – from voting against Russia in the UN Security Council, UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council. India has maintained that the principles of UN Charter should be followed and that the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all nations is sacrosanct. It has also – through talks at various levels, including between the Heads of State – repeatedly appealed to Russia to cease hostilities, and has kept in touch with Ukraine and sent humanitarian aid for the latter. India has – despite abstentions from UN – amply made its empathy for Ukraine very clear. India has also openly and repeatedly refuted certain fake propaganda being spread by Russia about Ukraine targeting Indian civilians in the war zone.

However, despite India’s unequivocal opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, India is also hemmed in by its complex relations with Russia – much like China has vocally supported maintaining relations with Russia, refusing to condemn it and condoning its ‘security concerns’, due to the practicality of China-Russia relations. China has also publicly criticized the sanctions against Russia, imposed by the West and is planning to host Putin for the BRICS summit. India has not done so.

In India’s case, India not only shares a historic relationship with Russia, spanning several decades, with Russia coming to India’s aid unequivocally in the events of diplomacy and war at a time when the West had isolated India, but an estimated 60-70% of India’s defence and military supplies are also from Russia. According to estimates, the share of Russian-origin weapons and systems in Indian forces is around 85% (Kaushik 2022). However, Russia’s share in India’s imports, while remaining high, has also come down, having reduced to about 50% between 2016 and 2020. Part of the reason is that several Russian deliveries were completed by 2020. However, the new import orders placed by India in 2019-20 will likely increase the import share from Russia.

Russia – for decades – has supplied some of the most sensitive and important weapons systems that India has required, including nuclear submarines, aircraft carriers, tanks, guns, fighter jets, missiles etc. At a time when the Western countries – despite relations with India – refused to supply strategic advanced weapons systems to India, Russia was the only country to supply India with nuclear-powered submarines, in many cases even transferring the technology. India’s biggest weapons export system is the Brahmos missile, jointly developed with Russia, including much of India’s missile platform. India even went to the extent of defying potential US sanctions to import the coveted S-400 missile systems from Russia – one of the world’s most advanced missile systems that even Turkey and Saudi Arabia defied US sanctions for.

India has also been in talks with Russia to lease two nuclear ballistic submarines, the first of which would be delivered by 2025. India has also commissioned an indigenously manufactured nuclear ballistic submarine, but most of the technology is based on Russian platforms. India’s only aircraft carrier in service – INS Vikramaditya – is also Soviet-made. Russia has supplied most of India’s fighter aircraft, and has also supplied the Indian navy’s sole operational aircraft carrier and the entirety of navy’s fighter and ground attack aircraft.

With a 60-70% supply parts dependency on Russia, any halt of Russian spares and logistical supply will punch a hole in our weapons systems which will cost India dear in the event of a confrontation with China or Pakistan. In the wake of tensions with China after 2020, Russia emerged as a key diplomatic mediator, with the Indian and Chinese foreign and defence ministers meeting in Russia to smoothen their relations. Indeed, at the height of the Galwan confrontation with China, India’s Defence Minister travelled to Russia to ensure that military supplies continued smoothly.

At the same time, India – like many other countries – also realizes that neither West nor Russia nor any other country will come to India’s aid in the event of a future crisis. Notwithstanding India’s symbolic abstentions at international fora, Indian statements and actions have amply conveyed that India’s empathy lies with Ukraine in this conflict. PM Modi – even while constantly in touch with Putin – has also maintained regular contact with Ukraine’s Zelenskyy.

Indeed, it is more apt to interpret that India’s position is being calibrated according to changing course of the invasion. India’s statements at the UN have made it clear that it has abandoned the principle of neutrality in favour of actively criticizing the war and appealing for peace, just short of criticizing Russia directly. Israel has also in its statements appealed for peace, intermediated between Russia and Ukraine, but Naftali Bennet has refused to outright criticize Russia. Indeed, in a phone call with Zelenskyy, Bennett advised him to compromise in the interest of saving the lives of people from further bloodshed. China has adopted a similarly changing and calibrating position, as has Turkey.

However, the conflict has now taken such a turn – with deadlocked negotiations and Russian unwillingness to cease attacks even as negotiations proceed – that most of the countries, especially India and China are being placed in a difficult position.

Under such circumstances, India should, and would be eventually forced to, come out in the open, take a strong stand and criticize Russia for its illegal invasion.

There is also the valuable lesson of nationalism and unity that India ought to take from Ukraine. The Russian invasion of Ukraine should open India’s eyes to what would happen if a similar scenario unfolded in India. No military capability alone can save India if the spirit of nationalism continues to elude us. While Ukraine has stood united against the invader, the Indian mentality, over the centuries, has been such that it can sell-out even the country for its own selfish interests. This is not only borne out in the case of historical colonial invasions of India, where powerful sections of Indian elite have always sat in the lap of the invaders, but is also true of the present.

Presently also, the Indian elite – who control India’s institutions, the whole system and education – are always raising their voice in favour of powers and forces that are hostile to national interest. Whenever there is conflict with Pakistan or China or whenever there are fundamentalist Islamic protests against India or some foreign or domestic scheme to defame India, this elite always sides with the anti-national powers. If such was the mentality in Ukraine, it would have already been captured. The reason such secular elite could thrive in India was because of enfeebled and emasculated attitude of majority of Hindu population of the country that has sought to prioritize selfishness over nationalism.

More than any external, outer machinery of defence, it is the spirit that matters. Ukraine had little outer machinery compared to Russia, but its spirit was unstoppable. That is why it could stand firm and rally the support of the whole world. The Indian government’s steps to become self-reliant in defence are commendable indeed and India does have high military capability, but the fundamental spirit of nationalism – which alone can lead to outer victory – is wanting. This is the main lesson India ought to learn from this war.

Towards Greater Insecurity

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine signifies an unprovoked attack on the sovereignty of a smaller, non-nuclear nation. It has many implications for the future of the world order, which are as follows –

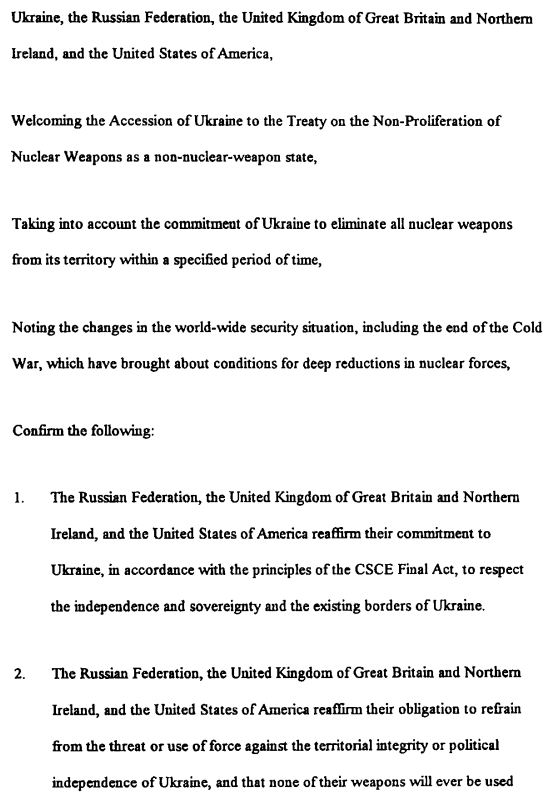

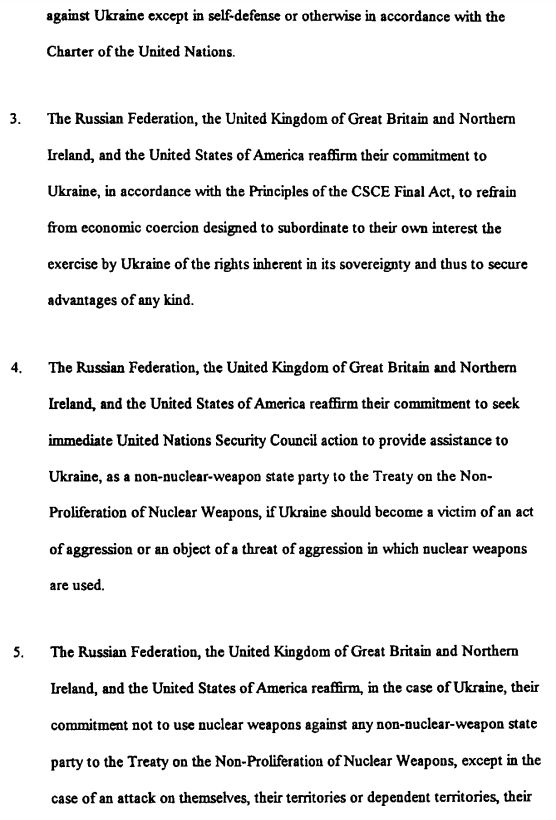

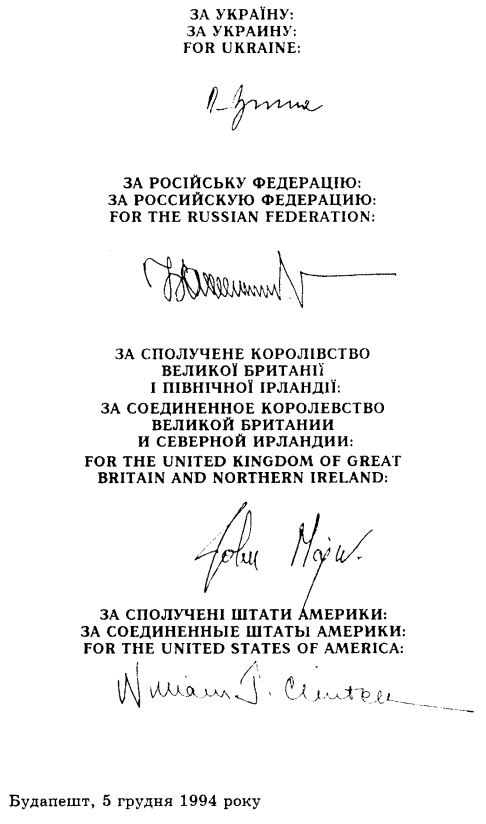

First, it lays bare the inefficacy of existing international and bilateral agreements and the toothlessness of what is touted as a ‘rules-based’ international order. Under an international agreement called the Budapest Memorandum signed in 1994, supervised by the UK, Russia and the US, Ukraine had undergone complete de-nuclearization between 1996 and 2001, relinquishing its third-largest nuclear arsenal in the world to Russia for decommissioning. The memorandum prohibited Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States from threatening or using military force or economic coercion against Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. This enabled the three countries to give up their nuclear arsenal and to become a part of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) as non-nuclear states.

In return for de-nuclearization and membership of the Non Proliferation regime, Ukraine sought legally-binding guarantees from the US that it would intervene in the event of an attack on Ukraine’s sovereignty – which the US did not agree to. In the final agreement, Ukraine settled for a diluted and weaker ‘security assurance’ to respect “the independence and sovereignty and existing borders of Ukraine” and the “obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine”. The memorandum committed the signatories to not use their weapons against Ukraine “except in self-defense or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.” It also stated that the signatories would “seek immediate UNSC action to provide assistance to Ukraine” if it was threatened or attacked with nuclear weapons. This was an assurance, but not a security guarantee, with the meaning of the term ‘security assurance’ being left deliberately vague. Often, the US has interpreted it as meaning assisting Ukraine in the event of conflict through the supply of military weapons (Borda 2022).

The West and Russia have repeatedly contravened the spirit of the Budapest Memorandum. During the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the subsequent response of the West in the form of economic sanctions, the toothlessness of the agreement was evident. In the subsequent years, the West has consolidated Ukraine’s military capabilities, but even in the case of the present invasion, the response of the West has been limited to military and financial aid, leaving Ukraine to fend for itself on the basis of its own capabilities and spirit, against a nuclear-armed neighbour.

This contravention of the agreement by both Russia and the West is making the Ukrainian public revisit the wisdom of giving up the country’s nuclear arsenal in the face of what now appears to be an ineffective security assurance. The pervasive thinking now is that, perhaps, possessing nuclear weapons could have acted as a deterrent against Russia. For, the probability of a war among nuclear-armed neighbours is lower, as nuclear weapons act as a deterrent due to the zero-sum outcomes – of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) – that would result from their use.

Second, there is a dawning realization that the fate of Ukraine can befall anyone tomorrow and that self-reliance and spirited resistance is key. The resistance put up by Ukraine has drawn out the war longer and put Russia in a precarious position – if Russia uses harsher weapons and massacres civilians it will be treated as a war crime and Russia would permanently become an international pariah, and, it has reached a point in invasion where it is reluctant to exit without an honorable, face-saving way out. The latter crucially depends on whether Ukraine yields to – presently, watered down – Russian demands of not joining NATO and recognizing the independent status of the eastern provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk. Russia is ready to ‘immediately’ stop the war if Ukraine does this. This will come more as a relief to the beaten Russian side and give them a way out. Ukraine’s citizens are anyway prepared to die to defend their sovereignty.

The Ukrainian resistance sets an important precedent in international politics. It shows that random, unprovoked attack on another country’s sovereignty is unacceptable in a civilized order of things. If Russia had succeeded in its misadventure, it would have set an extremely wrong precedent for other countries. The message would have simply been that might is right. While this message is still there, to some extent, it is diluted.

But the initial audacity of Russia has now put other countries on a path towards self-reliance and rapid militarization – even ‘pacifist’ nations like Germany and Japan. Germany has announced a 100 billion Euro fund to modernize its military and decided to raise defence spending from 1.5% of GDP to 2% of the GDP. Japan’s former Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, argued that “Japan should break a longstanding taboo and hold an active debate on nuclear weapons – including a possible ‘nuclear-sharing’ programme” (Borda 2022). Japan is also pressurizing the US to station some of its nuclear arsenal on Japanese territory. It has also demanded to know US’s position on Taiwan, in the event of a potential Chinese attack. Taiwan is also insecure about what China may do tomorrow. India swung into action on the very day Russia attacked Ukraine, holding a conference on self-reliance in defence. For every country, there now persists the thinking that we are all potentially Ukraine.

Third, there is also a realization among countries – especially US allies – that the West, especially the US, will not be of much help in the event of a conflict. They are on their own. During Cold War, due to division of world into ‘spheres of influence’ between US and USSR, competitive aid to countries for warfare was justified. But now this is no longer the case. The world is not divided into competitive spheres of influence between two great powers.

It is a multi-polar world, where every country is responsible for itself. It is also a precarious nuclear-armed world with rising reliance on artificial intelligence in warfare, in which no country would prefer seeking confrontation for the sake of another country. The international institutions are also weak, as are moral principles. While world has rallied behind Ukraine today, it may not always do so. For example, China rubbished the treaty with the British and integrated Hong Kong, with little that anyone could do. Same may happen with Taiwan tomorrow. EU and US might not be as forthcoming in the defence of an Asian country as they were for Ukraine – which is located in the heart of Europe – as they would not like to get involved in Asia.

In such a world, there is rise of insecurity and new forms of warfare. This insecurity and paranoia – combined with our egoistic inability to control the vital organization of external, automated machinery set-up by us – will only rise in times to come. This will pull the world into a far worse vortex than ever witnessed before, of which Russia-Ukraine war might only have been a diluted preface.

War and the Future of Humanity

“Only when man has developed not merely a fellow-feeling with all men, but a dominant sense of unity and commonalty, only when he is aware of them not merely as brothers, – that is a fragile bond, – but as parts of himself, only when he has learned to live not in his separate personal and communal ego-sense, but in a larger universal consciousness can the phenomenon of war, with whatever weapons, pass out of his life without the possibility of return” – Sri Aurobindo (CWSA 25: 611).

The pace at which the humanity is moving towards its self-destruction, buttressed by the scientific and technological means available at its disposal, has once again brought war to the centre-stage of world relations. The Russia-Ukraine war is a harbinger of the destruction of the fragile world order built on a false façade of liberal internationalism, as symbolized by institutions like the United Nations, and run on the whims of a few powerful countries. Amongst the most understated points of this war has been its brutality, which has been downplayed in the egoistic din of who is winning and who is losing. But some of the glimpses – as evidenced through the Bucha killings and torture of unarmed Ukrainian civilians – have come through due to the sheer brutality of the event. As per the mayor’s office in Mariupol, the place where Russia bombed a maternity hospital, nearly 5,000 people had been killed there alone (Crawford 2022). On the Russian side, on March 24, NATO officials estimated that there have been between 7,000 and 15,000 Russian military deaths (Crawford 2022). To think that this loss of lives and sheer suffering was completely unnecessary and the result of the whims and ego of an imperialist maniac once again lays bare the frailty of the international system evolved after the Second World War.

This fragile outer machinery is now under assault with the psychological damage already inflicted. It has taken us back to the 20th century era which was marked by wars, showing us how precarious and futile our arrangements and agreements are in the absence of the inner dynamism of the soul and the psychic being. For the sake of our endless greed and selfishness, we have looted the earth and advanced warfare. The selfishness that pervades our nature and lives is what drives our mechanical political machinery to subvert the basic principles of nationalism and national spirit. The perversion at the heart of the present war will likely project itself to relations between other nation-states and lead to much worse conditions for humanity, unless this war is conclusively ended with Russia being humbled and disabused of its assertion.

ANNEXURES:

Budapest Agreement of 1994

No. 52241

____

Ukraine, Russian Federation, United Kingdom of Great Britain

and Northern Ireland

and

United States of America

Memorandum on security assurances in connection with Ukraine’s accession to the

Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

Budapest, 5 December 1994

Entry into force: 5 December 1994 by signature

Authentic texts: English, Russian and Ukrainian

Registration with the Secretariat of the United Nations: Ukraine, 2 October 2014

Minsk Agreement of 2015

Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements

- Immediate and comprehensive ceasefire in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine and its strict implementation as of 15 February 2015, 12am local time.

- Withdrawal of all heavy weapons by both sides by equal distances in order to create a security zone of at least 50km wide from each other for the artillery systems of caliber of 100 and more, a security zone of 70km wide for MLRS and 140km wide for MLRS Tornado-S, Uragan, Smerch and Tactical Missile Systems (Tochka, Tochka U): -for the Ukrainian troops: from the de facto line of contact; -for the armed formations from certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine: from the line of contact according to the Minsk Memorandum of Sept. 19th, 2014; The withdrawal of the heavy weapons as specified above is to start on day 2 of the ceasefire at the latest and be completed within 14 days. The process shall be facilitated by the OSCE and supported by the Trilateral Contact Group.

- Ensure effective monitoring and verification of the ceasefire regime and the withdrawal of heavy weapons by the OSCE from day 1 of the withdrawal, using all technical equipment necessary, including satellites, drones, radar equipment, etc.

- Launch a dialogue, on day 1 of the withdrawal, on modalities of local elections in accordance with Ukrainian legislation and the Law of Ukraine “On interim local self-government order in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions” as well as on the future regime of these areas based on this law. Adopt promptly, by no later than 30 days after the date of signing of this document a Resolution of the Parliament of Ukraine specifying the area enjoying a special regime, under the Law of Ukraine “On interim self-government order in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions”, based on the line of the Minsk Memorandum of September 19, 2014.

- Ensure pardon and amnesty by enacting the law prohibiting the prosecution and punishment of persons in connection with the events that took place in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine.

- Ensure release and exchange of all hostages and unlawfully detained persons, based on the principle “all for all”. This process is to be finished on the day 5 after the withdrawal at the latest.

- Ensure safe access, delivery, storage, and distribution of humanitarian assistance to those in need, on the basis of an international mechanism.

- Definition of modalities of full resumption of socio-economic ties, including social transfers such as pension payments and other payments (incomes and revenues, timely payments of all utility bills, reinstating taxation within the legal framework of Ukraine). To this end, Ukraine shall reinstate control of the segment of its banking system in the conflict-affected areas and possibly an international mechanism to facilitate such transfers shall be established.

- Reinstatement of full control of the state border by the government of Ukraine throughout the conflict area, starting on day 1 after the local elections and ending after the comprehensive political settlement (local elections in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions on the basis of the Law of Ukraine and constitutional reform) to be finalized by the end of 2015, provided that paragraph 11 has been implemented in consultation with and upon agreement by representatives of certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in the framework of the Trilateral Contact Group.

- Withdrawal of all foreign armed formations, military equipment, as well as mercenaries from the territory of Ukraine under monitoring of the OSCE. Disarmament of all illegal groups.

- Carrying out constitutional reform in Ukraine with a new constitution entering into force by the end of 2015 providing for decentralization as a key element (including a reference to the specificities of certain areas in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, agreed with the representatives of these areas), as well as adopting permanent legislation on the special status of certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in line with measures as set out in the footnote until the end of 2015.

- Based on the Law of Ukraine “On interim local self-government order in certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions”, questions related to local elections will be discussed and agreed upon with representatives of certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in the framework of the Trilateral Contact Group. Elections will be held in accordance with relevant OSCE standards and monitored by OSCE/ODIHR.

- Intensify the work of the Trilateral Contact Group including through the establishment of working groups on the implementation of relevant aspects of the Minsk agreements. They will reflect the composition of the Trilateral Contact Group.

Participants of the Trilateral Contact Group:

Ambassador Heidi Tagliavini___________________

Second President of Ukraine, L. D. Kuchma___________________

Ambassador of the Russian Federation to Ukraine, M. Yu. Zurabov___________________

A.W. Zakharchenko___________________

I.W. Plotnitski___________________

Bibliography

Aleem, Zeeshan. 2022. MSNBC. March 5. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://www.msnbc.com/opinion/msnbc-opinion/russia-s-ukraine-invasion-may-have-been-preventable-n1290831.

BBC. 2022. British Broadcasting Corporation. March 24. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60125659.

Borda, A.Z. 2022. The Conversation. March 2. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://theconversation.com/ukraine-war-what-is-the-budapest-memorandum-and-why-has-russias-invasion-torn-it-up-178184.

Bremmer, I. 2022. Twitter. March 26. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://twitter.com/ianbremmer/status/1507736409079230464?t=oKT8k1qAH2CFgc31Tr1C2w&s=08.

Crawford, N.C. 2022. The Conversation. April 4. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://theconversation.com/reliable-death-tolls-from-the-ukraine-war-are-hard-to-come-by-the-result-of-undercounts-and-manipulation-179905.

CWSA 25. 1997. The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, War and Self-Determination. Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department.

- 2022. Ukraine: A short history of its creation. New Delhi: The Indian Express.

- 2022. What is NATO, and why is Russia so insecure about Ukraine joining the US-led alliance? New Delhi: The Indian Express.

Kaushik, Krishn. 2022. How dependent is India on Russian weapons? New Delhi: The Indian Express.

Kissinger, Henry. 2014. “To settle the Ukraine crisis, start at the end.” The Washington Post, March 5.

Mathew, Thomas. 2022. Ukraine: the pawn in the power game. New Delhi: The Hindu.

Suny, Ronald. 2022. The Conversation. February 28. Accessed March 13, 2022. https://theconversation.com/ukraine-war-follows-decades-of-warnings-that-nato-expansion-into-eastern-europe-could-provoke-russia-177999.